Sgt. John A Falconer

Congressional Medal of Honor

Warrensburg, MO

Birth:

|

January 1?, 1844 Washtenaw, MI

|

Death:

|

Apr. 1, 1900 Warrensburg, MO

|

He served during the Civil War as a Corporal in Company A, 17th Michigan Volunteer Infantry. He was awarded the CMOH for his bravery at Fort Sanders , Knoxville , Tennessee

John A. Falconer

Entered service at Manchester, Michigan

On the 20th Brigadier General Ferrero ordered the 17th Michigan to push the Confederates out of a building about 1,000 yards from the fort “doing material damage to my line of skirmishers.” Companies A and F moved forward followed by a five man “burning party”. The troops cleared the building and succeeded in applying the torch. On their move back to the Union line they were opened on by Confederate artillery, suffering two killed and four wounded.

|

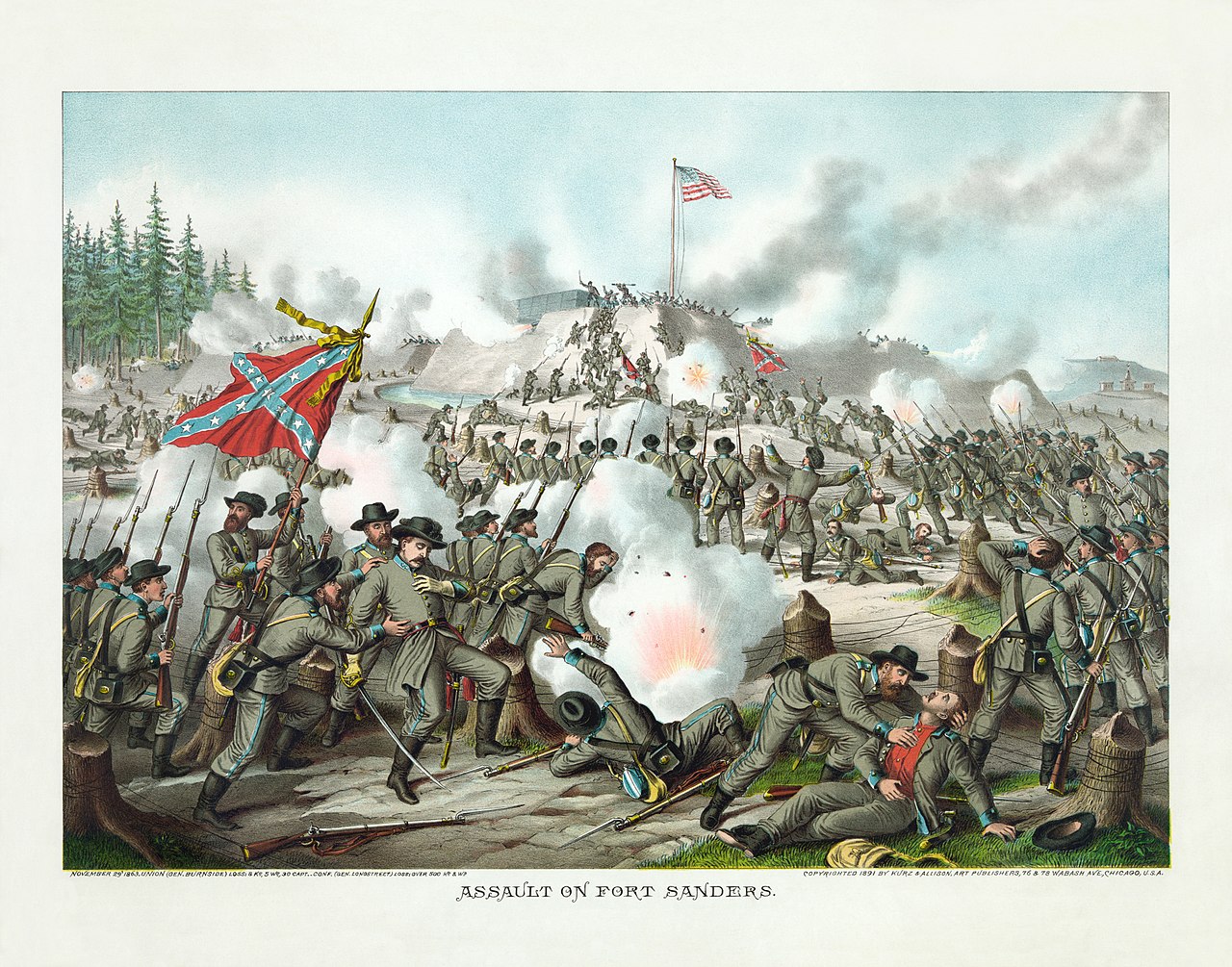

| Assault on Fort Sanders, TN |

His Medal was awarded to him on July 27, 1896. After his death, his family moved to the state of Washington

|

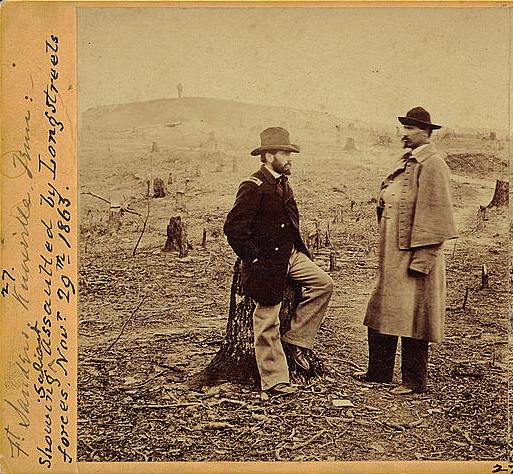

| Fort Sanders, TN |

|

Fort Sanders, Knoxville, TN Civil War, Sgt. John A Falconer

Before the attack, the Union soldiers soaked the sloped dirt walls of Fort Sanders. After the water froze the icy slope would be even more difficult for the Confederates to scale. On November 29, 1863, the Confederates attacked and failed in their attempt to take Fort Sanders. The 20th Michigan suffered 19 casualties, with two killed, eight wounded, and nine captured

On June 12, 1999, a special ceremony was organized by the Medal of Honor Society, Johnson County Missouri Historical Society, and the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War 1861-1865 in order to honor the heroics of John Falconer over 130 years earlier. Although John Falconer had received his medal in the mail before his death, there had been no official presentation of the award by a military officer until this ceremony. Bio by Bill Walker

|

|

| 1863 map of Knoxville with both Fort Sanders and the 20th Michigan.

Fort Sanders (November 29) Battle of Fort Sanders

Longstreet decided that Fort Sanders was the only vulnerable place where his men could penetrate Burnside's fortifications, which enclosed the city, and successfully conclude the siege, already a week long. The fort, named in honor of slain cavalry chief William Sanders, surmounted an eminence just northwest of Knoxville. Northwest of the fort, the land dropped off abruptly. Longstreet believed he could assemble a storming party, undetected at night, below the fortifications and overwhelm Fort Sanders by a coup de main before dawn. Following a brief artillery barrage directed at the fort's interior, three Rebel brigades charged. Union wire entanglements—telegraph wire stretched from one tree stump to another to another—delayed the attack, but the fort's outer ditch halted the Confederates. This ditch was twelve feet (3.5 m) wide and from four to ten feet (1–3 m) deep with vertical sides. The fort's exterior slope was also almost vertical. Crossing the ditch was nearly impossible, especially under withering defensive fire from musketry and canister. Confederate officers did lead their men into the ditch, but, without scaling ladders, few emerged on the scarp side, and the few who entered the fort were wounded, killed, or captured. The attack lasted twenty minutes and resulted in extremely lopsided casualties: 813 Confederate versus 13 Union.

As Longstreet contemplated his next move, he received word that Bragg's army was soundly defeated at the Battle of Chattanooga on November 25. Although he was ordered to rejoin Bragg, Longstreet felt the order was impracticable and informed Bragg that he would return with his command to Virginia but would maintain the siege on Knoxville as long as possible in the hopes that Burnside and Grant could be prevented from joining forces and annihilating the Army of Tennessee. This plan turned out to be effective because Grant sent Sherman with 25,000 men to relieve the siege at Knoxville. Longstreet abandoned his siege on December 4 and withdrew towards Rogersville, Tennessee, 65 miles (104 km) to the northeast, preparing to go into winter quarters. Sherman left Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger at Knoxville and returned to Chattanooga with the bulk of his army. Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, Burnside's chief of staff, pursued the Confederates with a force of 8,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, but not too closely. Longstreet continued to Rutledge on December 6 and Rogersville on December 9. Parke sent Brig. Gen. James M. Shackelford on with about 4,000 cavalry and infantry to search for Longstreet.

View of Fort Sanders, TN Civil War

|

On November 24 members of the 2nd Michigan regiment made a sortie to Confederate rifle pits in front of Fort Sanders, but were thrown back, leaving several of their wounded behind. When they called a truce to retrieve them, wrote Watkins, "Then you had ought to have seen the rebel brutes rush out of the pits and strip the dead. Oh if I ever felt like taking a man’s hearts blood, it was them devils."

|

Early in the morning of November 29th, enemy artillery began firing heavily on Fort Sanders and other points, while the guns of the fort boomed in response. In the frigid dawn 4,000 of General Lafayette McLaws' crack troops charged up the hill to the fort, quickly passing through the abatis -- sharpened logs thrust into the ground to fend off enemy attackers. "The brigade charged with reckless bravery," wrote Blair, "but were entangled in the noted trap of the 'Burnside wire.' Strung from stump around the fort, "Burnside wire" was an all-but-invisible tangled line of telegraph wire. Those who made it across this barrier found themselves in a deep ditch surrounding the fort, facing a nearly perpendicular palisade twenty feet high, a steep and slippery climb in the icy morning. The defenders poured a merciless fire into the ditch, with artillery batteries shortening the fuses on their shells and dropping them down to devastating effect.

|

Watkins described the battle in his aforementioned letter soon after daylight they opened on us from all their batteries or at least 5 positions and if the shell didn't fly around us I am no judge. The air was full of bursting shell but the most of them too high. I don't think that there was a man killed in the 3/4 of an hour that they shelled us and but one wounded and he was right beside us in a tent. I was standing up against the breastwork and saw the shell coming just as plain as day. We could hear them coming before they got anywhere near us and what a noise they make.

|

While this shelling was going on the rebels were forming for a charge on the fort and the first our folks new [sic] of them they were within 20 yards of the picket line and less than 300 from the point of the fort.

And on they came with a yell 3 columns deep and one in reserve...the rebels came over logs, wire, and stumps and planted their colors right on the outer slope of the fort. The slope there is on an angle of 45 degrees and about 20 feet from the top of the work down to the top of the ditch. Then the ditch is about 7 feet wide and 6 deep. They just piled in there on top of one another dead wounded and dying and the living to get away from the fire of our troops. One of them got up to one of the embrasures with some 4 or 5 behind him in front of a piece that has 3 charges of canisters in it, and he hawed right out and says surrender you yankee son of bitches. The words were hardly out of his mouth before the piece was pulled off and away went Mr. Reb and companions blown into Ribbons. But all of this did not last more than half an hour for those that were alive in the ditches began to call for quarters and the order was given to cease firing. There was arrangements made right off to cease hostilities till 7 o'clock in the evening. As soon as the firing stopped I went up and got on the parapet to look at them. And such a sight I never saw before nor do I care about seeing again. The ditch in places was almost full of them piled one on top of the other.... They were brave men. Most of them Georgians. I would give one of the wounded a drink as quick as anybody if I had it. That is about the only thing they ask for when first wounded. But at the same time I wished the whole Southern Confederacy was in that ditch in the same predicament.

|

Confederate losses in the assault on Fort Sanders amounted to 813, of whom 129 were killed, 458 wounded, and 226 captured. Union casualties in the fort numbered 13, of whom eight were killed and five wounded. Total union casualties, both inside and outside the fort, amounted to 20 killed and 80 wounded. Four union soldiers won the Medal of Honor for valorious service at Fort Sanders. Three -- First Sergeant Francis W. Judge of the 79th New York Infantry and Private Joseph S. Manning and Sergeant Jeremiah Mahoney of the 29th Massachusetts Infantry -- were cited for capturing enemy flags on November 29. One, Corporal John A. Falconer of the 17th Michigan Infantry, was awarded a medal for leading a "burning party" on a house sheltering enemy sharpshooters on evening of November 30, thus ensuring the success of a Federal charge on Confederate lines. Soon after the disastrous assault on Fort Sanders, Longstreet learned of Benjamin Bragg's defeat at Chattanooga -- a setback that made his own position untenable. He continued the siege until December 4, but hearing that a 25,000-man relief column under William T. Sherman was heading for the city, retreated northward with all his forces. The Confederates never again occupied Knoxville -- an important rail junction vital to their operations in Eastern Tennessee. On December 5, the 45th left the city in pursuit, having faced -- and passed -- its severest test of the war.

the-knoxville-campaign

John A. Falconer

Date of birth: 1844

Date of death: April 01, 1900

Burial location: Warrensburg, Missouri

Place of Birth: Michigan, Washtenaw

Home of record: Manchester Michigan

AWARDS AND CITATIONS

Medal of Honor

Awarded for actions during the Civil War

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Corporal John A. Falconer, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 20 November 1863, while serving with Company A, 17th Michigan Infantry, in action at Fort Sanders, Knoxville, Tennessee. Corporal Falconer conducted the "burning party" of his regiment at the time a charge was made on the enemy's picket line, and burned the house which had sheltered the enemy's sharpshooters, thus insuring success to a hazardous enterprise.

General Orders: Date of Issue: July 27, 1896

Action Date: November 20, 1863

Service: Army

Rank: Corporal

Company: Company A

Division: 17th Michigan Infantry