Slave narratives, a folk history of slavery in the United States from interviews with former slaves. Missouri Narratives, Volume X--Charlie Richardson. Ex-slave.

Charlie Richardson, an ex-slave from Warrensburg Missouri, had some very blunt comments about the institution (of slavery):

Audio Quote from Transcript

Audio Quote from Transcript

"We called it 'putting them on the stump.' But the 'stump' was neither a block or a stump, it was a big wooden box. We always knew when they were going to sell because they would let them lay around and do nothing. Fattening them up for market."

Audio Transcript Link 5.34 length

Audio Transcript Link 5.34 length

Charlie Richardson followed his master, a Confederate officer from Virginia, through several battles in the Civil War before the officer returned home and Richardson drifted to Fayetteville.

Missouri Department of Natural Resources Division of State Parks Slavery's Echoes: Interviews with Former Missouri Slaves. Please give credit to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources' Missouri State Museum. Link

Missouri Narratives, Volume X--Charlie Richardson. Ex-slave. |

| Glasgow, MO Paper 25 Aug 1859, pg.3 100 Negroes Wanted |

Mother: Ann Dowle Smith Richardson

Link

512 N. Rone Street

Webb City,Missouri

By Bernard Hinkle, Joplin, MO 1938

Well, Charlie, let us sit right down here on this bench and chat awhile. Mr. Hal M. Wise, editor of "The Sentinel" here in Webb City, told me about you.

You won't mind if I ask you a few personal questions about the days of slavery will you? No Sah I'd be glad to tell you anything I know.

Thank you Charlie.

Thank you Charlie.

The first thing I would like to ask is your name Charles, Charlie or Charley? Everybody calls me Charlie.

Where were you born Charlie? I was born at Warrensburg, Missouri.

What year were you born in Charlie? They always said I was born in March. Didn't never give no day. Jest March.

A serious argument over slavery took place in Congress when Missouri asked to be admitted to the Union in 1819. Missouri was a territory making up part of the Louisiana Purchase. Many settlers in Missouri came from southern states. Slavery was allowed in Missouri.

At that time, there were exactly the same number of "free" states (states which did not allow slavery) as there were "slave" states (states which did allow slavery). This meant that there was a balance of power in the United States Senate, where all states are represented equally. The "free" states had a majority in the House of Representatives because the northern states had a larger population than the southern states.

When Missouri's request to be admitted reached Congress, a northern Congressmen proposed that it should be admitted only if it promised to free its slaves. Southerners in Congress angrily replied that the North had no right to require this.

In December 1819, Maine also asked to be admitted to the Union. The House of Representatives was ready to approve Maine's request. There was no slavery in Maine. However, at first the Senate would not allow Maine to enter the Union. Southern senators refused to admit Maine as a free state unless the northern senators would agree to admit Missouri as a slave state.

In 1820 Henry Clay of Kentucky helped arrange a compromise that allowed both Maine and Missouri to enter the Union. By means of the Missouri Compromise, as the new agreement was called, several laws were passed. Congress admitted Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state. Slavery had now spread to one more state. At the same time, Congress drew a line westward across what was left of the Louisiana Purchase. This line, set at 36° 30' North latitude, divided free and slave territory. In the future, any states formed north of the line would be free states. Any new states formed south of the line would be open to slavery. Link

|

How old are you now? The old-age pension man said I was 86 this year.

Now Charlie, please give me the name of your parents and where came from? My Ma's name was Ann Smith, the first time, cause my Pappy was Charlie Smith. Then my Pappy died and my Ma married a man named Charlie Richardson. He was my step-Pappy so I took his name. Both my own Pappy and my step-Pappy were were just plain negroe's and born in Warrensburg, but my Ma was a Black Hawk Indian girl, kinder light in color and purtty. Her Ma was a full-blooded Black Hawk and she married to Grandaddy Richard Dowle,which was my Ma's name 'fore she married.

Tell me Charlie, did you have any brothers or sisters? Yes Sah, I had two sisters and five brothers but none ain't here now.

Describe your home and "quarters" the best you can? Log Cabins that's what they was. All in a long row-piles of'em. They was made of good old Missouri logs daubed with mud and the chimney was made of sticks daubed with mud. Our beds was poles nailed to sticks standing on the floor with cross sticks to hold the straw ticks.

How did most of you cook—in the cabins or in the "big house"? Most of the negroes cooked in the cabins but my Mammy was a house girl and lots of times fetched my breakfast from the Masters house, Most of the negroes, though, cooked in or near the cabins. They mostly used dog irons and skillets, but when they went to bile anything, they used tin buckets.

What food did you like best Charlie. I mean, what was your favorite dish? It warn't no dish. It ware jest plain hoe cake mostly. No dishes or dish like we has nowadays, No Sah, this here hoe cake was plain old white corn meal battered with salt and water. Hoe grease.

How much grease? Jest 'nough to keep it from stickin'. This here hoe cake was fried jest like flap-jacks,only it were not. Hot flap-jacks I mean. When we didn't have hoe cake we had ask cake. Same as hoe cake only it was biled. Made of cornmeal, salt and water and a whole shuck,with the end tied with a string. We never had no flap-jacks in the cabins. No Sah! Flap-Jacks was something special for only Master Mat Warren and the Missis. That makes me remember a funny story about flap-jacks. My Ma brought some flap-jack stuff down to the cabin one day you knowt jest swiped it from the house where she worked. Well, Ma was frying away to git me something special like when she hears the Missis comin' with her parrot. So, Ma hides them flap-jacks right quick. Soon the Missis come in our cabin and was talkin to my Mammy when that crazy old parrot he begin to get fussy like something was wrong. He were a smart parrot and outside, generally called us all "niggers, niggers". Well Sah, he kept squawking and the Missis kept savin, shut up! shut up!, what's the matter with you?"

Purtty soon the Missis go over to sit in a chair Ma had with a big pad in it. and before the Missis could set down that crazy parrot begun to yell, "Look out Mam,it hot', look out, Look out!". The Missis turned to my and said "What's the matter here?" My Ma answered,"Taint. nothin" the matter Missis. And then that fool parrot hollows agin,"It's hot! It's hot's And sure'nough the missis she get a peek at a flap-jack stickin'

through under the pad, where Ma hid them. And Ma almost got a good lickin fer that. That parrot could out-talk Marster Warren and wouldn't eat anything we would give him cause he was afraid of being poisoned by us "niggers". They use to tie him out in the field to watch the negroes at work, and when he went in the house at night Ma said he would hollow and yell the most unholy lies about those "niggers" and what they tried to do to him. Sometime we'd get him to drink some whey milk, the Marster bad given us when it was so sour it would make a hog squeal. The parrot would call us some awful' names for doing that.

Clothing of Slaves

What clothing did the older boys and men wear Charlie? Big boys and grown folks wore jeans and domestic shirts. We little kids wore jest a gown. In the winter time we wore the same only with brogans with the brass toes.

You said awhile ago that they gave you "Whey" milk. That's a very poor grade of milk isn't it? Yes Sah, It's the poorest kind of poor milk. It ain't even milk. It's what is left behin, when the milk is gone.

And coffee. How about coffee. Didn't you have any coffee to drink? We has coffee some time, but it ware made of burned corned meal. Once in awhile the slaves while makin' coffee for Marster Mat out of the wheat would burn a pan purposely and he would give it to them to make coffee with. That was purtty good coffee. Some time they got whupped for burnin' it, cause he knowed they burned it too much for his coffee, on purpose—jest so they'd git it.

Now Charlie, you said you were born in Warrensburg, Missouri. Were you born on Mat Warren's place? Yes Sah.

How many slaves did Mr. Warren have?

150 I understand they sold off attractive women slaves and husky men.

How is it they didn't sell your Mother? She ware a house girl. Purtty and light in color,so they wanted to keep her for that job.

Did they sell your father? "Yes Sah, they did. That is, they sold my step-Pappy as my own Pappy was dead"

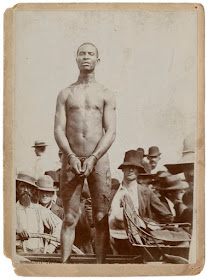

Speaking about your step-Pappy being sold reminds me: They say that the expression" selling slaves on the block" is not true. That is not always true? We never had no "block" on Mat Warren's place. We calls it "puttin'em on the stump". But the "stump" were neither block nor stump, it were a box. Big wooden box.

I have heard it said that some slaves brought big prices. Tell me, if you will, how much your step-Pappy was sold for?

Well Sah, there was some buyers from south Texas was after to buy my step-Pappy for two years runnin!, but the Marster would never sell him. So one time they comes up to our place at buying time( that was about once every year) and while buying other slaves they asked Mat Warren if he wouldn't sell my step-Pappy, cause he was a sure 'nough worker in the field—the best man he had and he could do more work than three ordinary men. But the Marster tried to git rid of that buyer agin by saying I don't take no old offer of $2,000 for Charlie, and I won't sell under $2,055. The buyer he said right quick like. "Sold right hare". So that's how he come to leave us and we never seed him agin. Like to broke my Mammy up, but that's the way we slaves had it. We didn't let ourselves feel too bad, cause we knowed it would come that way some time.

|

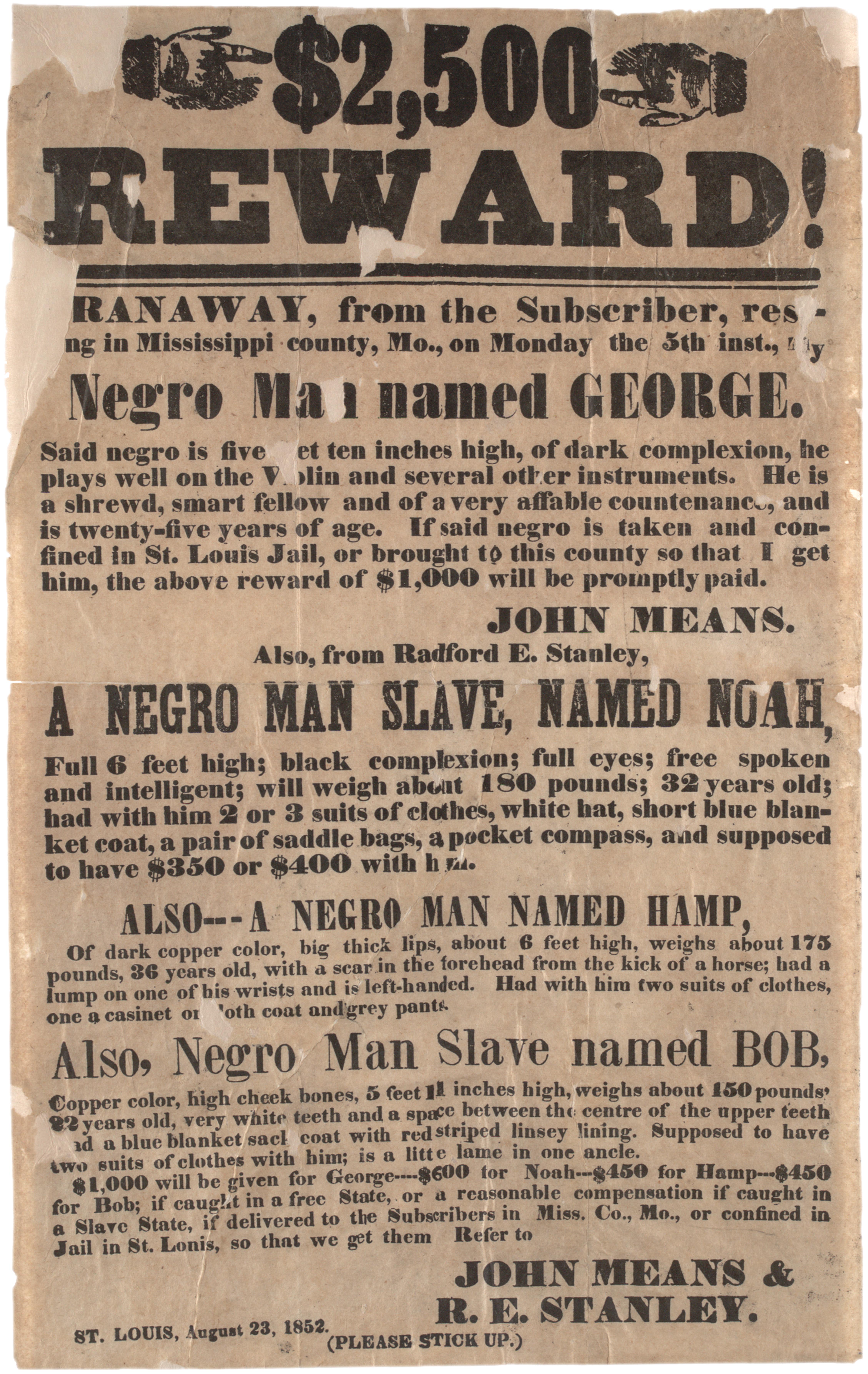

| Slave auction flyer |

But my Ma she liked that Charlie and she feeled it mos, We always knowed when they was going to sell, cause they would let them lay around and do nothing. Jest feed them and git fat. They even smeared their faces with bacon rine to make 'am look greasy and well fed afore the salt. They never had no grease to eat only now and then Mat Warren he makes it look like them nigger is well fed and cared for the buyers would stick pins in 'em and examine their teeth like horses.

By the way Charlie, what kind of jails did they have in those days?

They never had no jails. Your back was the jail, When you done something serious Marster Mat Warren called in the "whuppers" and they made your back bleed and then rubbed salt into the skin. After that they chained you to a tree and let you suffer.

What did you do as a child around the place? I carried in the water and wood to the Missis house and helped Ma.

What time did you all get up in the morning? A big bell hanging in the center of all the cabins rang at 4 A.M. and then most of the grown folks worked from dawn till eleven at night. We never had no Saturday's off like they do now. Nor no Sunday's off neither.

What kind of house did the Master live in?

The Marster he have a very fine home. About ten rooms, built of common brick. It ware a very purtty house; great big like.

What did you do,Charlie, after work at night? Mostly, go to bed. We kids did early. But I wake up lots of times and hear my Ma and Pappy praying for freedom. They do that many times. I hear it said that Abraham Lincoln hears some slaves praying at a sneaked meetin' one time, askin' the Good Lord for freedom. And it is believed that Abraham Lincoln told them, that if he were President he would free them.

Did you ever play any games or dance any? No! No games, no play, only work. We had to be mighty careful we I didn't use a pencil or any paper or read out where the Marster could see us. He would sure lick us fer that.

What do you think of Abraham Lincoln?

I think he ware the greatest man in the world.

Do you remember much about the war Charlie? Not very much. I was only seven then, but I remembers that those Bushwhackers came to steal my Master's money but he wouldn't tell where he hid it. Said he didn't have any. They said he was telling a lie cause no man could have so many salves and not have some money. He did have 150 slaves but he wouldn't tell where the money was hid. So they burned his feet, but he still wouldn't tell 'em he had hid it in the orchard. No Sah! He jest didn't tell. Them Bushwackers though, were not so bad as them Union soldiers. They took all our horses and left us old worn out nags; even took my horse I use to ride.

When I was married I was a coachman and wore my coach clothes—Bee-gum hat (colloquial high silk hat), black double-breasted flap tailed coat and black broadcloth pants. My shoes were low and had beads all over the front. I looked like Booker T. Washington.

And I like him most next to Abraham Lincoln.

|

| Charlie Richardson's Coachman's Outfit would have been similar to this. Beegum /Bee-gum Hat |

I use to work for Judge Brown in Fayetteville as coachman.Then I come here and worked for Mrs Louise Corn of Webb City for 13 years. I ain't workin' now, only firin' the boiler for the First National flank in winter. My son-in-law Sam Cox, he works at the Bank on the side and I help him a little. Mostly, I'm jest a man about town.

Now, tell me in passing, Charlie, do you remember any men passing through your place in Warrensburg, looking for escaped slaves? Yes I remember some tough men driving like mad through our place many times,with big chains rattling- We called them slave hunters.

They always came in big bunches. Five and six together on horse back. Patrollers they was.

|

| Slave Patrols Link |

Bernard Hinkle

Joplin, Missouri

January 27, 1938

JOHNSON COUNTY MISSOURI SLAVES

1820s 0

1830s 0

1840s 556

1850s 879

1860s 1,896*

Missouri Department of Natural Resources' Missouri State Museum.

*Slaveholders in Johnson County 465

April 10, 1954

BORN IN SLAVERY DIES AT FULTON, MO. WEBB CITY, Mo., April 9, 1954

Charles "Charlie" Richardson, 94 years old, died today in a hospital at Fulton, Mo., where he had been a patient for the last eight years. He was widely known in Webb City, where he lived with his daughter's family for 18 years, and was employed by the late Tom Coyne. He was born in slavery near Warrensburg, Mo., to Sarah and Charles Richardson in 1857. When he was 6 or 7 years old the slave owners moved to a farm near Neosho. After he was grown, he worked as a horse trainer at Fort Smith, Ark., and could recall Belle Starr and many notorious characters of the early days. In 1920, he came to Webb City to make his home with his daughter, and lived here until senility made it necessary that he be admitted to the Fulton hospital.

Title Emancipation Ordinance of Missouri. An ordinance abolishing slavery in Missouri. Allegorical

print commemorating the ordinance providing for the immediate

emancipation of slaves in Missouri. (See also no. 1865-1.) The ordinance

was passed on January 11, 1865, three weeks before the Thirteenth

Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was proposed by Congress. Female

personifications of Liberty (left), Justice (below), and Missouri

(right) are set in the niches of an ornate architectural framework.

Liberty wears a blue cape and liberty cap, holds a sprig of oak leaves,

and is accompanied by an eagle. Missouri, in a red cape, raises a palm

branch in her right hand and with her left grasps a yoke that she breaks

under her foot. Justice is seated, blindfolded, and holds a sword and

scales. She is flanked by two putti, one white and one black, each

holding a document. The white child's document is labeled "Natural

Philosophy" and the black child's "Rights of Man." On the left is a

small vignette of a rural scene with a man, woman, cow, goat, vineyard,

and wheat field. On the right is the state capitol building at Jefferson.

In the topmost register are the Missouri state arms and other

emblematic devices. The printed legend continues: "Be it ordained by the

people of the State of Missouri in Convention assembled That hereafter

in this State there shall be neither slavery not involuntary servitude,

except in punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly

convicted, and all persons held to service or labor as slaves are hereby

DECLARED FREE," followed by signatures of the delegates.