|

| Flora May “Flo” Quick Mundis, aka "Tom King", "China Dot" from Holden, MO and Mrs. F. B. Neal, Warrensburg. |

|

| Holden, Missouri - Home of Flora Quick |

Years later when a relative was interviewed he said she was buried in Missouri in the private family plot. If this is true she may have been quietly laid to rest in a grave in the Quick Cemetery.

|

| Quick Cemetery Location? NW of Blairstown, MO |

The St. Joseph Weekly Gazette

United States of America

Thursday, August 17, 1893

St. Paul, Minn., Aug. 14. The St. Paul bankers are dazed tonight over a robbery at the First National bank at 11:00 o'clock this morning, a single man being able to seize a $5,000 bag of gold in the presence of twenty people and disappear in a crowd. The police have been searching for him ever since, but there is small prospect that he will be caught. Renaldo Lares, a trusted representative of the Merchants' National bank, accompanied by I. H. Jacobs, porter of the Merchants bank just come into the First National bank to make a settlement with the clearinghouse. The funds consisted of three bags containing $5000.00 each in gold in a small steel box with odd money also, and in all about $20,000 (about $520,000.00 today. Arriving at the teller's window, Lares opened the box and removing the bags placed them on the window lodge close by the teller's window. Resting the bags for the moment on the ledge, Lares began to pay in the loose money, and was busy with this when he heard a step at his right, and turning instantly, he saw the robber grab two of the bags and dart around the post toward the door. Lares made a leap and succeeded in reaching the door almost as quickly as the thief and would no doubt have been able to catch him, or at least follow him, had not a man, undoubtedly the accomplice of the thief, hero interposed by crowding Lares to the wall and giving the man with the bag a clear sweep. In an instant everything was excitement, the clerks and clearing house men rushed out into the general banking banking office, but the gold and robbers were as completely gone as though the earth had closed over them.

TOM KING. A History of Oklahoma's Daring Female Horse Thief. Holden. Mo. Aug. 13,

Flora Quick Mundis, alias Tom King, the noted horse thief of Oklahoma Territory, who has gained such an unenviable notoriety, is well known in this locality, She is about 19 years old and a daughter of the late Daniel Quick,

|

| Father, Daniel Quick

BIRTH 24 Jun 1819

Holmes County, Ohio, USA

DEATH 7 Aug 1889 (aged 70)

Johnson County, Missouri, USA

BURIAL

Quick Cemetery

Johnson County, Missouri, USA

|

|

| Daniel Quick Homestead, Johnson County, MO |

|

| Flora Quick -Notorious "Tom King" - "Chinese Dot" Oklahoma Horseback Outlaw from Holden, Missouri |

REMARKABLE MISSOURI GIRL WHO WAS A Bandit

Her Lot Cast With Desperate Men, She Became Their Leader in Crime Her Career as Tom King in Oklahoma

Her Visit to Old Home in Missouri Last Month The End in Clifton, Arizona.

CLINTON. Feb. 20, 1903. Special Correspondence of the Sunday Post-Dispatch

Verily, truth is stranger than fiction; and the way of the transgressor is hard. How well verified are these ancient saws In the life of "Chinese Dot," a noted character who was shot to death in Clifton. Ariz. From Flora Quick, a bright-witted and innocent Missouri farm girl of 15 years ago to "Chinese Dot." prominent in an Arizona town, is a far cry, and much that is marvelous lies between. When the old Blair road, now the Clinton division of the Frisco, was building through Western Missouri, Old Dan Quick was a wealthy and eccentric character noted over Henry and Johnson Counties. Owning 1500 acres of fair land, he went about in ragged garments that a trump would spurn. He had lost an arm and leg, and it is related related that on one occasion, after cashing in at a Kansas City bank a draft that required four figures, he sat down on the steps of the bank to rest, holding his tattered hat in hand, whereat a pitying passerby tossed him a careless penny. Old Dan leaped to his feet with voluble cursings and told the alms giver he could buy him over and over again. The village of Quick City, on the Frisco, was built on his land. The building of the Blair road made lively times at the Quick ranch near Blairstown. Henry County, Mo. Flora was admired by the graders and contractors. and unfortunately fell in love wit John Ora Mundis (Mundus), a handsome devil-may-care young fellow, fellow, well-meaning enough, perhaps, but easily influenced. Soon afterward they moved to Oklahoma. They were fortunate In securing a fine piece of land, and seldom did a young married couple start out humbly In life with brighter prospects. But Mundus fell in with a band of "rustlers" who led him from bad to worse, until he became a horse thief and outlaw, with a price upon his head, hunted by the officers and despised by all good men. The wife bore slights of the neighbors, hoping by her patience and gentle love to win him back, for he occasionally visited her and lavished fair promises. One night Mundus came home drunk and in a quarrelsome mood. A family row ensued, and then struck her In the face with his open hand. That blow transformed the patient, the gentle, loving woman, Into a murderess and outlaw. Being of a high-strung, sensitive nature smarting more under the humiliation than from pain, she snatched her husband's pistol from its hostler and shot the outlaw through the breast, and then, woman-like, all the bitterness is gone, she knelt before the prostrate form and begged forgiveness from the silent lips. As the heart of her husband ceased to beat, this poor friendless girl-wife, fearing the vengeance of an unfriendly community, donned a suit of her husband's clothes, took his pistols and rode away In the darkness.

"Tom King's" band of outlaws soon became notorious and feared of all men. Under daring leadership, their crimes easily I surpassed those of a border gang and for months they eluded officers where possible and fought when driven to bay. So desperate and reckless were their depredations that large posse of officers and citizens was finally organized. Many of the gang were killed, and the rest captured, but not until all were lodged in jail was the discovery made that "Tom King." the dare-devil leader, was none other than Flora Quick in trousers. Flora's jail life was brief. She resumed skirts, and laid siege to her Jailer. He fell an easy victim to her blandishments. A general jail delivery soon followed, and Flora Quick was again in the saddle at the head of her old gang of bandits, while by her side rode her friend and liberator. the Jailer. In a battle occurring the following day the marshal of Oklahoma City was killed and another officer dangerously wounded, but Flora and the enamored Jailer escaped. For several years nothing was heard from Flora until last fall when she came back to her childhood home at Quick City (Johnson County, MO) to visit her brother, a well-to-do and highly respected young farmer. As her visit drew to a close she came to Clinton (MO) with her brother. The woman's dash and she attracted much attention. They went into a photography studio, and brother and sister at together for a portrait. The photographer, a young lady, studied her subject from an artistic point and asked the favor of posing her for an individual portrait, but with a singular glitter of the eye, and emphatic gesture the woman declined. This was Jan. 2o (1902) last. The following day she left Missouri forever.

|

| Clifton, AZ Early 1900's |

Horrified citizens, rushing in. found the woman barely alive. She directed that crowd to where she kept her jewels, worth many thousands of dollars, but she refused to reveal her identity, and implored her acquaintances not to search into her past. In the excitement attending her death her diamonds were forgotten, and thieves secured them. William Garland was a gambler, 25 years old and a dope fiend. But it was reserved for the coroner's inquest to lift the veil from "Chinese Dot's" past life and discover her identity with Flora Quick, the (Holden) Missouri farm girl, and "Tom King, the Oklahoma bandit.

"China Dot," Who Met Violent Death at Clifton, Ariz., Daughter of a wealthy Missouri Farmer.

Guthrie, Ok., Feb. 9, 1903

A woman known as "China Dot," shot and killed by William Garland at Clifton, Ariz., January 28, has been identified here as "Tom King," a woman bandit, once with the Henry Starr gang of desperadoes who infested Oklahoma and Indian territory. She wore men's clothing when she lived in this country. Her maiden name was Flora B. Quick. Her father, Daniel Quick, was a wealthy farmer near Holden, Mo. It is alleged that the woman took part in the Santa Fe train robbery at Red Rock several years ago. Afterward she was arrested at Minco, I. T., for horse-stealing, but broke jail at El Reno and was never heard of again in Oklahoma.

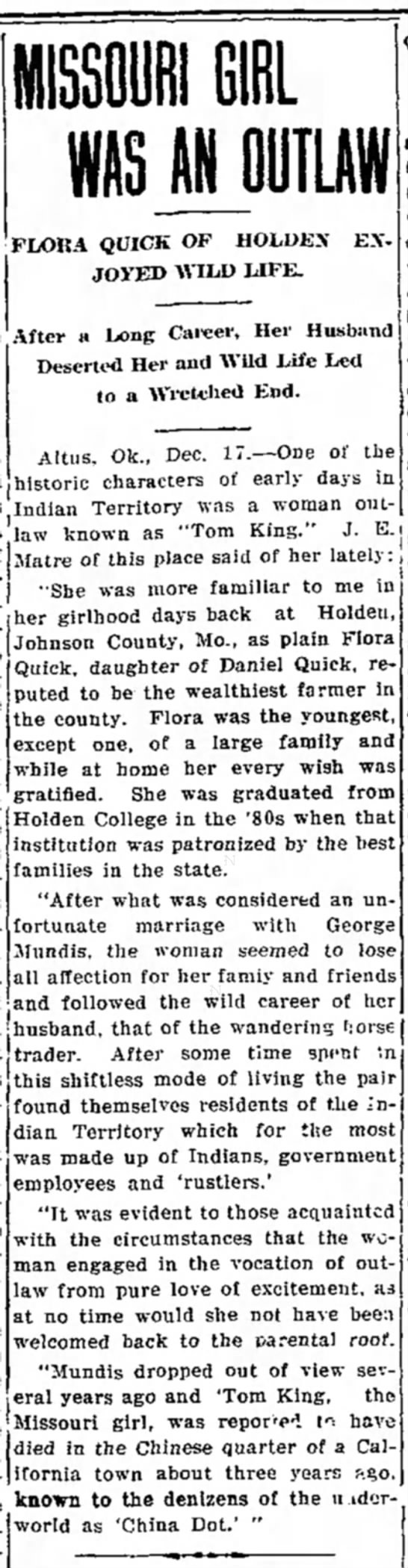

Altus, Ok., Dec. 17.—One of the historic characters of early days in "Indian Territory" was a woman outlaw known as "Tom King." J. E. Mat re of this place said of her lately: "She was more familiar to me in her girlhood days back at Holden, Johnson County, Mo., as plain Flora Quick, daughter of Daniel Quick, reputed reputed to be the wealthiest farmer in the county. Flora was the youngest, except one, of a large family and while at home her every wish was gratified. She was graduated from Holden College in the '80s when that institution was patronized by the best families in the state.

"After what was considered an unfortunate marriage with George Mundis, the woman seemed to lose all affection for her family and friends and followed the wild career of her husband, that of the wandering horse trader. After some time spent in this shiftless mode of living the pair found themselves residents of the Indian Territory which for the most was made up of Indians, government employees and 'rustlers.' "It was evident to those acquainted with the circumstances that the woman engaged in the vocation of outlaw from pure love of excitement, as at no time would she not have been welcomed back to the parental roof. "Mundis dropped out of view several several years ago and 'Tom King, the 'Missouri girl, was reported to have died in the Chinese quarter of a California town about three years there known to the denizens of the world as 'China Dot.' "

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

GIRL OUTLAW: The Death of Flora Quick Mundis aka 'Tom King'

The exciting, checkered and lawbreaking career of Flora M. Quick Mundis, who went by the name 'Tom King' is believed to have come to a violent and sad in January of 1903 in Clifton, Arizona. Some records have her name as "Flora B. Quick" but many descendants seem to favor the "M".

At about 4:30 a.m. on January 28, 1903, in apartments over the Siranas Italian Saloon, a woman known locally as "China Dot" was shot four times by William Garrison.

A bullet smashed her cheek entering her brain, one passed through her breast piercing a lung, one cut through her liver with an upward angle severing her spinal cord and paralyzing her. One bullet broke her right arm.

The shooter, William Garrison (Garland/Garfield?), son of Globe, Arizona James Garfield (former mayor of Springfield, IL), then turned the gun on himself. A bullet in his right temple took the top of his head off.

At the time of her death in 1903, after seven years living in Clifton, the papers of "China Dot", said local papers, revealed her to be "Mrs. F. B. Neal" of Warrensburg, Missouri. As to the 'China Dot', it was said she earned her nickname by being a consort of the Chinese men who were in the area working for various mining companies. These Asian workers suffered racial prejudice and superstition as bad, perhaps worse, than local Hispanic, Native-American and African-Americans.

An alleged diamond trove valued at about $1,500 was missing and had been since the day of the shooting. This was a common theme when popular working girls died. Many prostitutes gave the appearance that they were better off than they were for a variety of reasons. Often officials and family found they had little more than enough to cover the cost of a burial.

In a short time it was being claimed this was the noted Oklahoma female outlaw, 'Tom King" aka Flora Quick Mundis. Details are lacking as to how this identification occurred other than one mention of a telegram sent to Missouri. One early newspaper had claimed she never allowed a photograph, and even granting some hyperbole, the issue of identification remains a question mark.

The news accounts are shallow of many facts. It is apparent that in several cases the news stories were more fiction than fact. Colorful characters attract lurid tales like a magnet on a merry-go-round. She could have only been a successful escapee by using sexual allure; instead several articles indicate she merely outwitted guards.

Some researchers, on genealogy and historic sites, have also expressed a question if the woman in Arizona might have been the sister of Flora. Ellen Quick McGee apparently disappears after heading to Oklahoma but one story seems to indicate that the woman followed her sister in many ways.

A tantalizing article appears in 1894 that seems to support the possibility. The only article that gave good details on an Ettie/Effie (spelled both ways in some articles) McGee was "Tom King" Caught in Fredonia, KS." Weekly Oklahoma State Capital of Aug 11, 1894 that gives her an alias of Jessie Whitewings. This woman was masquerading as a man but was described as flaxen haired, 23, and very fleshy by this time. It said was of her that she had been in Fort Sill and El Reno. I did find in the 1889 OKC Directory a listing for a "McGee, J. b-10 l-32 Noble, wife". Noble was a street south of Reno, about the SW 3 or 4th region now. This may or may not be the same couple but the time period is correct. Could she have disappeared to Arizona? If not, where did she go? Is it possible the labels about Flora being a fallen woman might have confused the two sisters? If Jessie was in Guthrie at the same time as Flora it might be easy for such a confusion to have occurred. Was "Jessie Whitewings" the sister or was someone else simply using the name?

The woman who, as a young woman, had ridden the streets of Guthrie in fine dresses, who masqueraded as a man to become a highly successful horse thief, had, according to articles about her death, had become a prostitute. This seems out of character for a woman who donned, successfully, the male persona to effectively lead an outlaw life.

Most were stories, even some that alleged to be actual local interviews, were labeled by at least one reporter as totally false and the creation of overactive imaginations among newsmen. Whatever the true case was, she was a woman who kept her secrets. Even to her alleged death there is a veil of mystery. Most news accounts indicate she was identified as Tom King but there is scant information about who made that identification. One article indicated authorities sent a telegram to Missouri seeking information on the person named on papers found in China Dot's rooms in Clifton, Arizona. The response returned an identification as "Flora Quick Mundis." No articles indicated who made that ID in Missouri or if anyone who had actually seen Flora/Tom viewed the body of China Dot.

She loved adventure and excitement and I am sure that she is pleased that after over one hundred years her story can still generate a lot of adventure, mystery, and excitement. It is the way she would have liked it.

Rose Dunn aka "Rose of the Cimarron", along with "Cattle Annie", "Little Britches", Jessie Finley (Finley), and Flora Quick Mundis aka Tom King would fill dramatically the void left by the mysterious murder of Belle Starr in 1889 near Eufaula. A fascinating page of truly unique history...found in Oklahoma...on the fringes of "Hell."

Select Sources:

"Tom King". Guthrie Daily News (August 18, 1893, pg.1). Identifies her alleged history and labels her a "female horse thief."

"Mrs. Mundis Breaks Jail." Guthrie Daily News (June 28, 1893, pg. 1). Identifies jail break out of June 27 in Oklahoma City. Notes among those escaping were" William Roach (rapist), Ernest Lewis (Train robber), Mrs. Mundis alias Tom King ('noted female horse thief') who had escaped from jail just the week before. The escape was made by cutting the steel bars of the cells and digging through the brick wall.

"A Bad Girl." Weekly Oklahoma State Capital (Guthrie), (August 26, 1893, pg.1). Identifies her as living in Guthrie at corner of Grant Avenue and 4th Street. Notes no scandal had been attached to her until she swore out an arrest warrant on charge of rape for Dr. Jordan (who had disappeared from town).

"She Loved Excitement." News (Frederick, MD) (Sept 16, 1893, pg. 2). Identifies her as wife of livery man and horse dealer, Mundis. Notes she had 'disappeared' some six months prior and that it was understood she was a 'daughter of a Cherokee Indian of some prominence.' Where, and why, she disappeared for some six months is a matter of some speculation. Other sources indicate she returned with her hair short, wearing men's clothes and calling herself Tom King.

"Tom King Breaks Jail." Phoenix Arizona Republican, December 10, 1893, pg. 4). Notes escape from El Reno jail, O.T. Unlikely she will be captured, it states, because she was on a 'fleet horse' and 'was riding like the wind.'

"A Horse Thief." Gettysburg (August 21, 1894, pg. 1). Shares the story she was a "quarter" Cherokee, that her people lived near Springfield, Missouri, and that 1 and one half years ago she was arrested on charges of being complicit with the Wharton Train Robberies and horse theft. Verifies she had escaped first from the Guthrie jail, then the Oklahoma City jail and then the jail in Canadian County, El Reno.

"Chinese Dot Dead Clifton Tragedy" Phoenix Arizona Republican (January 29, 1903;1). First of several articles beginning the process of identifying 'China Dot' with first one name, Mrs. B.F. Neal, and then to Flora Quick Mundis aka Tom King.

"Tom King Dead." Oklahoma State Register (February 5, 1903, pg. 1). A short piece that identifies, for some reason, the person who shoots the woman identified as Flora Quick Mundis, aka Tom King, as someone named "Fletcher."

"Miss 'Tom King' - Oklahoma Girl Bandit" by Nancy B. Samuelson (Twin Territory Journal, Dec.-Jan. 1990-1991, pp. 8-9).

"Flora Quick aka Mrs Mundis aka Tom King aka China Dot" by Nancy B. Samuelson (Quarterly of the National Association For Outlaw And Lawman History, Inc. {NOLA}, Oct.-Dec. 1996, V.22 N.4 pp. 22-27).

"Shoot From The Lip" by Nancy B. Samuelson (Shooting Star Press, 1998, pp. 6, 50-51, 111, 154, 181, 186).

"Bob Dalton's Bandit Bride" by Harold Preece (Real West Magazine - Mar. 1965 p10).

"Flora Quick, Alias Tom King" by Leola Lehman (Golden West magazine - Nov. 1966 p20 & The West magazine - Oct. 1974 p32);

"The Making of an Outlaw Queen" by Robert F. Turpin (Real Frontier magazine - Mar. 1970 p26).

"The Outlaw Was No Lady" by M. P. Lehman (Real West magazine - Oct. 1972 p.65).

"She Was The Jailor's Killer Sweetheart" by Glenn Shirley (Westerner magazine - Mar./Apr. 1974 p.46).

"Chris Madsen's Elastic Memory" by Nancy Samuelson (NOLA Journal Jan-Mar. 1992 p9).

["Chinese Dot Dead Clifton Tragedy" Phoenix Arizona Republican (January 29, 1903;1); Chris Enns at http://chrisenss.com/flora-mundis-lady-horse-thief-an-excerpt-from-the-bedside-book-of-bad-girls/ and various articles imply and state she was a prostitute. However, a look at her time line indicates that prior to her adventures as a horse thief, there did not appear to be adequate time for a long term employment in the trade of a soiled dove. It should be remembered that newspapers and facts did not always go together during the late 19ths and early 20th century; opinion was as good as fact and rumor better than hard evidence.]

Posted by MARILYN A. HUDSON, MLIS at 4:37 PM

A Woman in Men’s Clothing

Posted on August 29, 2016 by Marcie Brock

A Woman in Men’s Clothing

Flora Quick aka Flora Mundis aka Tom King aka China Dot

by C.K. Thomas

China Dot couldn’t possibly have committed all the crimes attributed to her by Flora Quick and John Mundis overzealous news reporters of her day. Born Flora Quick in 1874, orphaned at the age of 15, and then married to a man who was after her inheritance, she soon made the decision she would survive by any means possible.

After her marriage to scoundrel Ora Mundis failed, Flora began riding horseback dressed in men’s clothing, stealing horses, and calling herself Tom King. Her true identity and gender became known when she landed in an Oklahoma City jail for horse theft. Newspapers reported her escaping jail at least twice and never being convicted for her crimes.

For a time, Flora turned tricks and even ran a brothel in Guthrie, Oklahoma, with her friend Jessie Whitewings. Reports claimed she robbed trains and banks as well, but in reality it seems she stuck to horse rustling. Sadly, she was killed by a jealous lover in the back of Sirriani’s Italy Saloon in Clifton, Arizona, at the beginning of 1903.

The most quoted story concerning her death attributes the deed to her lover, Bill Garland. Flora and Bill quarreled while high on opium, and Bill shot her four times before shooting himself in the head. News reports of the incident described the four gunshot wounds in graphic detail, and while Flora managed to live several hours following the shooting, Bill’s suicide was instantly fatal.

It’s difficult to find the truth about Flora Quick, considering all the tales written about her notorious life. Newspapers.com search results produce conflicting reports, and while many articles and books try to unravel her history, it appears we may never know the whole truth about this frontier woman who masqueraded as a man. In the 29 years she lived, she managed to leave behind a legacy that rivals more familiar Wild West characters such as Annie Oakley and Clamity Jane, who were written about in dime novels and sensationalized in news reports of the era.

SOURCES:

August 23, 2015 article by Marshall Trimble

Findagrave.com__________

C.K. Thomas C.K. Thomas lives in Phoenix, Arizona. Before retiring, she worked for Phoenix Newspapers while raising three children and later as communications editor for a large United Methodist Church. The Storm Women is her fourth novel and the third in the Arrowstar series about adventurous women of the desert Southwest. Follow her blog: We-Tired and Writing Blog.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2013

Did you know Tom King was a woman?

Everyone knows Belle Starr, but how about Flora Quick?

According to Nancy B. Samuelson, writing in the National Association for Outlaw and Lawman History, Flo usually dressed as a man, and was mostly known in the Twin Territories as Tom King.

Our own Jacquie Rogers knows of Tom King and her alias of Flora Quick, but many do not. Still, she/he was outlaw enough for yarns by the hundreds to spring up around the country—problem is, few can be substantiated.

Harold Preece, author of The Dalton Gang, wrote several articles about Tom King. One was titled Dalton’s Bandit Bride. Starts to sound like Duckbill Hickock and Martha Jane Canary, doesn’t it?

Preece claimed that King was the smoothest and shrewdest of any woman outlaw, and compared to her, Belle Starr was merely a sly frontier slut. He said King was a regular member of the Dalton Gang who spied for them and stole horses for them. King was in love with Bob Dalton, it seems, so after he met his death in Coffeyville, she went on to form her own gang.

According to Samuelson, “Preece went on to claim Flo was killed by a posse near Wichita, Kansas, in 1893, and was buried in the family plot in Cass County, Missouri. His Tom King stories were spun from his imagination, using nothing but hot air and perhaps some old timer’s unreliable recollections.”

Chris Madsen said he arrested Tom King several times, as did Bill Tilghman and Heck Thomas. But, says Samuelson, there is no evidence first that Tom King knew the Daltons, or that any of the “Three Guardsmen” ever arrested her, took her to jail, or had any contact with her.

So what’s the real story?

The first record of Tom King alias Flora Quick alias Mrs. Mundis alias China Dot is found in the Oklahoma State Capital, a newspaper in Guthrie, on May 26, 1893. A.G. Baldwin was in Oklahoma City yesterday and saw Mrs. Mundis, who once lived in this city, but is now in jail on the charge of horse stealing, having played the romantic role of “Tom King.” She is still dressed up in men’s clothing and essays to play the mail part by whistling a tune occasionally.

Newspapers of the day say that Flo was the youngest child of Daniel Quick, a wealthy farmer from Holden, Missouri. He apparently died in 1889 and left an estate of 2,400 acres and some $13,000 in personal property. Flo’s marriage, some report, was to a worthless man, John Ora Mundis, whose sole objective was to latch onto her share of the estate. Sometime later, the couple announced that they were “bad, bad people and not to be trifled with.”

Tom King’s career seems to have started with horse stealing in May 1893. In jail, she met up with train robber Earnest Lewis and rapist William Roach. They broke out of jail together. At this time, Tom King alias Mrs. Mundis, was 18 years old, 4’8’’ in height, and weighed about 130 pounds. Svelte she was not.

King stayed out of jail until July, when she was arrested by Deputy Morris Robacker in front of the Baxter & Commack livery stable in Guthrie. He took her back to Oklahoma City (and may have collected a $50 reward).

Once again she escaped, and Sheriff Fightmaster chased her into the Osage country and jailer Wise captured her coming out of a cornfield near Yukon. A day later she was at large again.

It’s interesting to note that while Tom King was arrested and jailed on charges of stealing horses several times, she was never convicted. She also escaped from jail more than the average person incarcerated. One wonders how.

Just listen to this newspaper article. (El Reno Herald) The report that a deputy sheriff eloped with Tom King is too ridiculous to think of. It is worse than a hallucination.

The story was false. But that didn’t keep the press from having a hay day. At least two other newspapers carried the story, and since then, nearly every article or story about her has some version of the elopement tale (including this one).

The Watonga Republican wrote of her: Tom King’s name is Mrs. Mundis. She rides astraddle and takes whiskey straight . . . The way the authorities of the territory identify Tom King is by her feet. She is terribly pigeon-toed . . . It would be awful if Miss Tom King should take it into her head to read that Old Maid settlement in the strip . . . As an editor in Oklahoma has expressed it, “Tom King just inserted herself in a pair of pants and lit out. . . Tom King and the average Oklahoma jail do not speak as they pass by.

In early 1894, reports said Tom led a gang that robbed stores. Then she was captured in Fredonia, Kansas. Bill Tilghman was assigned to bring her and her accomplice, Jessie Whitewings, back to El Reno. Thing is, reports said Flo was pregnant. Newspapers scoffed, but jailers tiptoed and seemed not to know what to do. Then she was released, and she fell from sight for some months.

More legends were made through newspaper reports in 1895, in the Coffeyville Daily Journal, for example. She was said to have been a gang leader and to have been a horse thief extraordinaire. The State Capital, a newspaper in Guthrie, wrote: . . . She is the leader of a gang of thirteen desperate characters who are operating along the eastern border, stealing the best horses. They do not bother with anything except the best, and run them into the Seminole and Choctaw countries. “Rabbit,” a famous racer owned by Bill Chenault, was stolen by the gang, but was recovered by the payment of $200. Flora’s alias is Tom King, and she dresses in men’s clothes and has the appearance of a 20-year-old boy. She rides like a Centaur and is a splendid shot with a Winchester or revolver.

Then came news of her death.

She was killed in Clifton, Arizona, in late January 1903. She claimed to be part Cherokee and lived with a Chinese man named Jim Mannon. This led to her becoming known as China Dot. She tired of Mannon and took up with a man named William A. Garland. The two quarreled in a room in the back of Salvadore Sirrianni’s saloon. Garland shot Tom King four times, then blew the top of his own head off. Both were addicted to opium, it seems. No one seems to know where Flora Quick alias Tom King is buried.

(This was taken from a much more detailed article by Nancy B. Samuelson in the Quarterly of the National Association for Outlaw and Lawman History.)