|

| Confederate First National Flag carried at the Battle of Blackwater, Mo. (Dec 18, 1861) at Milford/ValleyCity - Near Warrensburg - Knob Noster, Missouri |

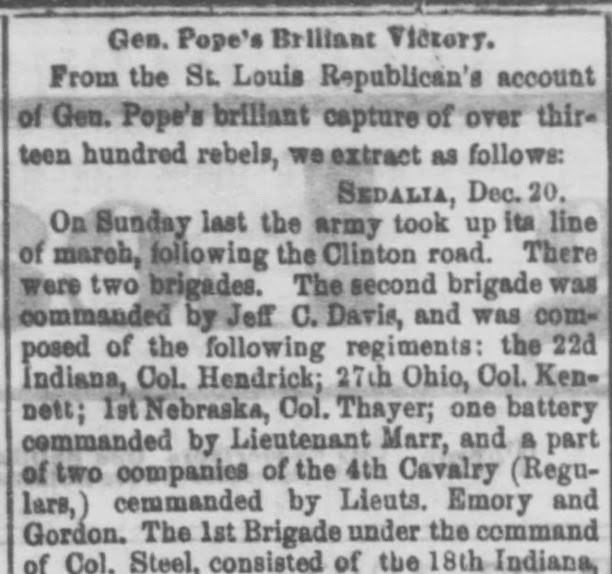

Gen. Pope's Brilliant Victory.

From the St Louis Republican's account of Gen. Pope's brilliant capture of over thirteen hundred rebels, we extract as follows: SEDALIA, Dec. 20. 1861

On Sunday last the army took up its line of march, following the Clinton road. There were two brigades. The second brigade was commanded by Jeff C. Davis, and was composed of the following regiments: the 22nd Indiana, Col. Hendricks; 27th Ohio, Col. Kennett; 1st Nebraska, Col. Thayer; one battery commanded by Lieutenant Marr, and a part of two companies of the 4th Cavalry (Regulars,) commanded by Lieuts. Emory and Gordon. The 1st Brigade under the command of Col. Steel, consisted of the 18th Indiana, Col. Patterson; 8th Indiana, Col. Benton; 14th Indiana, one battery, Capt. Klaus, and four companies of the 1st Iowa Cavalry, Major Torrence. With this force Gen. Pope marched eleven miles the first day, in the direction of Clinton, camping on Honey Creek. Next day a march of thirty-seven miles brought him to Shawnee Mounds, where he received definite information that the enemy his men so much desired to meet, were encamped twelve miles northwest. The rebels were reported to be in considerable force, and seven hundred cavalry under command of Lieut Col. Brown, was sent against them. The number of this rebel force could no one ascertained with certainty, but it is supposed to have exceeded one thousand. Here began a rapid flight and a hot pursuit that did not end until Colonel Brown reached Johnstown, in Bates county.

While encamped near Warrensburg, Gen. Pope received information that a large rebel force, numbering twelve or fifteen hundred, were encamped near Milford on Blackwater. Having sent Merrill's Horse out on the road leading from Milford(Valley City) to Warrensburg, to intercept the enemy should they attempt a flight, he marched the remainder of the army to Walnut Creek, on the road leading from Warrensburg to Knob Noster, and there encamped. Milford is distant from Knob Noster northwest about ten miles, and there the enemy were encamped on the north side of Blackwater totally unconscious of the proximity of the Federal army. From the camp on Walnut Creek to Milford is about six miles. Gen. Pope sent 450 cavalry, under command of Jeff C. Davis, to Knob Noster, with instructions to proceed thence directly upon the rebel camp. By this disposition of his forces Gen. Pope bad the rebels completely surrounded at all points they were likely to attempt Sight, his main army being on the South, Merrill's Horse on the West, and Col. Davis, the attacking party, coming down upon them from the southeast. At a glance it will be seen no better disposition of the troops could have been made to secure a triumphant Issue. As a support to Col. Davis, a section of artillery followed him under command of Major Speed Butler, with one company of the 1st Iowa cavalry. The attacking force immediately under the command of Col, Davis, was a part of the 1st Iowa regiment, led by Major Torrence, and parts of two companies United states regulars, commanded respectively by Lieuts, Gordon and Emory. With this force, not exceeding 450 men Col. Davis marched upon the enemy. It is plain the rebels had no idea of the close proximity of them, Pope’s army, for when few men were thrown forward by Col. Davis, the rebels eagerly sought to surround them in considerable force, and retired precipitately when they discovered the remain der of his force. Prior to this, however, the rebel pickets were driven in by the regulars under Emory and Gordon, whose men succeeded in killing one picket and capturing another. The regulars led the charge on the bridge over the creek where they were encamped, and a gallant charge it was, for the bridge was well guarded. Having forced the bridge, the enemy guarding it retired rapidly, some following the rot straight out from the creek and up a hill, and others following along the creek to the main camp. Lieut Gordon with great gallantry followed the latter, charging upon them with all speed, and coming upon the enemy in large force, be discharged two volleys at them, and in return received heavy fire from nearly all the rebels in camp, by which he lost one man mortally and nine severely wounded.

Col. Davis then moved his men on the hill immediately in the rear of the enemy's camp, which was situated in a bend in the creek, and soon had the foe between himself and the creek, and completely surrounded. The remainder of the story is soon told. The rebels, thus finding themselves hemmed in, had no alternative, but to fight or surrender. They chose the latter, and before another gun was fired they hoisted a white tag, and asked for thirty minutes to consider what they would da. It was then getting dark, and Col. Davis told them the lateness of the hour forbade the demand. They then asked for time to return to their commander, and come again. This was granted. The white flag was borne by a brother of Colonel Robinson, who was in command of the rebels, and soon he reappeared with Col. Anderson, and an unconditional surrender agreed upon. The whole force thus taken was 1,340 men, including three colonels and seventeen captains. In addition to the prisoner of war, the glorious little army under Col Davis also captured over a thousand stand of arms, near four hundred head of horses, sixty-five wagons, and a large amount of baggage, tents, provisions, etc. In a conversation with Col. Magoffin, I learn the rebels were terribly frightened, from the moment of the first attack. A picket, it is said, came into their camp under whip and spur, having run his horse tor two miles at the limit of his speed, and reported the Federals were coming down upon them 6,000 Strong. CoL Magoffin asked him, "how do you know there were 6,000?' "Why." he replied, “haven't I been watching them pass by for the last three hours?" and with this evidence of the faithful discharge of his duty the picket again mounted his horse and put out in search of " some vast wilderness," where, doubtless, be is tonight, housed in a hollow log. 1 learn from some of the prisoners that a large number of the cavalry fled precipitately at the first alarm, and made good their escape. So alarmed were they that they imagined the unarmed recruits, who had been sent to the rear, to be the enemy. The prisoners present a most mournful appearance. They are motley beyond description in appearance, and in every way poorly prepared to endure the hardships of a winter camp life. Very few have overcoats, and the remainder nave only blankets or comforts. Their capture is to themselves an act of humanity. I notice among the prisoners about sixty contrabands, who seem to take the capture of themselves and masters as a remarkable piece of goal luck.

GENERAL POPE SCATTERS AND CAPTURES SECESSIONISTS IN MISSOURI

Home

1861 Campaigns

Armies

Battles, Campaigns & Raids

Confederate Armies

Missouri State Guard

Operations to Control Missouri

Regular Army

State Militia & Volunteers (US)

US Armies

December 18, 1861 (Wednesday)

Four thousand poorly-equipped Rebel recruits of the Missouri State Guard, only half of which were armed, were hardly a match for Union General John Pope’s troops, who spent the previous day scattering the lot of them across southwestern Missouri. By dawn of this day, the last remaining five hundred or so were dispersed after midnight near Johnstown, fleeing towards Butler and Papinville to evade capture.

Pope then turned his force north, on the road to Warrensburg, to await the return of the many details of cavalry that had been sent out to chase down the recruits. A bit after dawn, they arrived, as did one of Pope’s spies.

The spy told him that another large body of the Missouri State Guard was marching south from Waverly and Arrow Rock, two towns along the Missouri River. They planned to encamp just south of Milford, near where the Clear Fork reaches the Black River, ten miles north of Warrensburg. Pope decided to intercept them. He stretched his own 4,000 from Warrensburg, east to Knob Noster, covering all routes south. He then dispatched Iowa and Regular Cavalry, under the direction of the unfortunately named Col. Jefferson C. Davis (no relation to the secessionist President) to Milford in order to turn the Rebels’ left flank, getting into their rear. Another cavalry unit was sent to hit the enemy’s right and rear, uniting with Col. Davis.

All the while, the main body moved four miles south of the Missouri State Guard encampment, ready to move at a moment’s notice. Late in the afternoon, Col. Davis found the Rebel camp opposite the mouth of Clear Fork, driving in the enemy pickets, who escaped across Black River over a long, narrow bridge. Their comrades, a stronger picket line, waited on the other side.

Davis then determined to take the bridge, charging it with his entire command. The Rebel pickets broke and scampered through the woods to their main body. Once across the bridge, two companies of Union cavalry formed line of battle and advanced upon the Rebels, who opened a volley of various small arms fire.

Balls from pistols, rifles and shotguns sang through the air, killing one and wounding eight. Davis pressed the assault and the Rebels began their retreat south. At some point, perhaps a scout or a messenger informed the Missouri State Guard commander that their line of retreat was cut off to the south and west. Realizing that he was surrounded by a larger force than his own, he had no choice by to surrender.

General Pope captured the entire Rebel command, including 1,300 men (and three colonels), 1,000 stands of arms, 500 horses, and seventy-three wagons full of gun powder, lead, tents and other provisions.

As darkness had fallen, both Union and Secessionist troops bedded down for the night, rising to a freezing morning. The prisoners were marched to St. Louis, while Pope’s men returned to Sedalia. Since they set out on the 15th, they had marched 100 miles, capturing 1,500 prisoners and over 2,000 weapons and 100 wagons.1

This little action, though small, was demoralizing to secessionists in western Missouri. General Sterling Price, with the main body of the Missouri State Guard near Osceola, sixty miles south of Warrensburg, realized that his attempts to gather recruits for his army were useless. He was convinced that Missouri had been abandoned by the Confederacy, who had no plans to send any troops into the state.2

- Pope’s report from the Supplemental Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Part II, p22-23. [↩]

- General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West by Albert E. Castel. [↩]

No comments:

Post a Comment