|

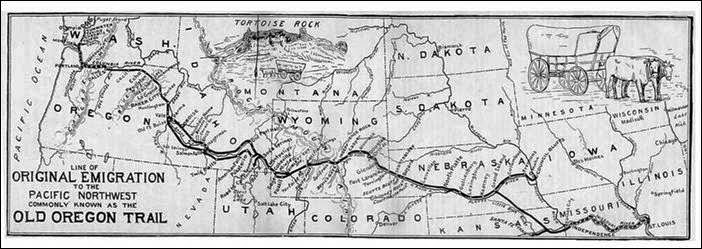

Ward Wagon Train Massacre 1854 - Began the journey in Johnson County, Missouri Originally published on this page in 2013

Started in Warrensburg, Missouri

Canyon County Idaho, Wagon Train Started in Johnson County, Missouri 360 Degree View of the site Shoshone killed 18 of the 20 members of the Alexander Ward party, (from Johnson County, MO) attacking them on the Oregon Trail in western Idaho. This event led the U.S. eventually to abandon Fort Boise and Fort Hall, in favor of the use of military escorts for emigrant wagon trains.

August 19, 1854, Lake Massacre (Boise, Idaho)

A large emigrant train heading to Oregon had split up into three sections, and the last four wagons had fallen several miles behind. About 70 miles southeast of the old Hudson's Bay Company post of Fort Boise, 11 Shoshone Indians approached the group of 4 families and 2 unattached young men. Ostensibly, the Indians sought to trade for whiskey. The emigrants said they had none. The Indians shook hands, appearing friendly, then opened fire, killing George Lake and fatally wounding two others in the party, Empson Cantrell and Walter G. Perry. The emigrants returned fire and wounded two Indians. The Shoshones stole five horses and rode off.

August 20, 1854, Ward Massacre (Caldwell, Idaho)

The day after the Lake Massacre, the vanguard of the same large but dispersed wagon train to Oregon was about 25 miles southeast of Fort Boise on the Snake River Plain, just east of present-day Caldwell, Idaho, when a party of 30 Shoshones approached Alexander Ward's five-wagon train of 20 emigrants. One Indian tried to take a horse by force, threatening an emigrant with his weapon. The white man shot the Indian down, starting a slaughter. The Shoshones killed Ward and raped and tortured several women, killing some. They hung children by the hair over a blazing fire. One boy, 13-year-old Newton Ward, was shot with an arrow and left for dead. His 15-year-old brother, William, took an arrow through the lung but lived. He hid in the brush until the Indians left, then wandered for five days until he reached Fort Boise. While the massacre was taking place, a group of seven emigrants under Alex Yantis, backtracking in search of stray cows, saw the commotion. They rushed in and rescued Newton Ward, but the Shoshones killed one of them, a young man named Amens, in the process.

Outnumbered, Yantis's party had to leave the few survivors to their fate while they raced to Fort Boise. When the Indians left, they took 46 cows and horses and more than $2,000 in money and property. A rescue party of 18 men arrived two days later, only to bury the mutilated bodies.

In addition to Amens, the Shoshones killed 18 of Ward's party. Some Indians may have been wounded, but it is not known for sure.

|

|

|

Cemetery notes and/or description: The Ward Family Massacre: When Wm. Alexander Ward and his small wagon train reached the Boise River Valley they felt it was the climax of their trip. Behind were months of travel through the debilitating, never-ending desert heat. Not far ahead was a larger wagon train, giving them a confident feeling of security. They drove off the road August 20, 1854, to rest and have lunch by the Boise River. The 20 emigrants, including Ward's wife, four sons, and four daughters; and John Frederick, Adolph Shultz, Dr. Adams, Charles Adams, Samuel Mallagan, William Babcock and several others, were preparing to continue their westward trek when one of the Ward boys rushed up to cry that a horse had been stolen by Indians. Several men were accompanying the party on horseback, and one of these, named Amond or Amen, was dispatched with three others to recapture the horse. The wagon train moved on toward the road, the women and children drowsing in the heat. Ward led the party on horseback, and the other men walked or road by the wagons. When they reached the road the emigrants were ambushed by a band of Snake Indians. Ward fell dead in the first flurry of shots. Amond/Amen joined the melee and was killed as he tried to rescue one of the Ward girls who was being dragged away. The rest of the men held off the hostiles until sundown, but the rain of arrows and rifle bullets felled them all. Although William and Newton Ward were shot through with arrows, they each managed to crawl into the brush and hide. Driving the wagons with the women and children into the bushes, the Indians tortured their victims, burning alive three of the Ward children. The men in the larger wagon train ahead were quick to ride back when they heard the firing but were too late. They buried the dead. Finding the wounded Newton Ward, they carried him back to their train. William Ward, unconscious, lay unnoticed in the bushes. He made his way to Fort Boise a few days later, the arrow still in his lung. Newton and William Ward were the only survivors of the massacre. (They were taken in by family members in Lane County and both lived until 1925.) When three of the Indians were caught they were tried and found guilty. One was shot as he tried to escape. The others were hanged at the scene of their depredations. The gallows were there for many years as a warning to other warrior Indians. The site of the Ward Massacre is near what is now Middleton near Caldwell, Idaho. Take Highway 30 east to the city limits. Turn right at the sign pointing to Municipal Rose Garden. Continue straight ahead 2.8 mi. on a gravel road. Turn right on gravel road 0.9 m., then right again at 0.8 mi. to the monument on the left side of the road. Here the highway follows the exact course of the Oregon Trail. In earlier days the graves of nine victims of the massacre were preserved. Later the owner of the farm plowed them under and planted alfalfa.

Ward-Masterson Wagon Train Would Have Looked Similar to this Scene

OREGON TRAIL JOURNAL, LETTERS, ETC.

The original journal was apparently copied by Harvey H. Jones and sent to family back east. The copy was then again copied, along with the letters, by O.S.J. [?Jones]. Occasional words seem to have been omitted in the process. I worked from photocopies of the handwritten copies of the journal, records and letters. This is an exact copy of whatever was in the manuscript (including obvious errors) except that letters and notes on ferries have been inserted into their chronological order.

Jones appears to have copied his journal in section and sent each section off as it was completed. Apparently, the last section had not been copied when he was killed in the White River Massacre.

Manuscript frayed - dates of first few entries worn away. Dates marked ? are first attempts at restoration

Aug 15 - Traveled 11 miles over a rough road. Saw a great many dead cattle. Camped by a brook (Jones manuscript:10).

Aug 16 - Traveled 20 miles without watering our cattle, over rough roads. Camped on Boise River (Jones manuscript:10).

Aug 17 - Traveled 16 miles. The country is poor along here. Camped on Boise River (Jones manuscript:10).

Aug 18 - Traveled 12 miles. Plenty of game and fish along here. Camped on Boise River (Jones manuscript:10).

Aug 19 - Traveled 12 miles. The Indians stole a cow as we were passing through some high rushes. Camped on Boise River (Jones manuscript:10).

Aug 20 - Started back to find the cow. Six men with me all on mules and horses. We met young Grant soon after we started. He said he had not seen the cow, he had passed one wagon a few miles back and that she might be with them. We met the wagon, the cow was not with them, the proprietor was Alfred Mastison [Masterson] a man who had traveled with Mr. Yantis on the forepart of the journey. We told him that the Indians acted very bold and saucy along here and that we thought he was presumptions to be traveling by himself. We told him he had better hurry on and overtake our train, that we thought he could do it that night if he hurried (Jones manuscript:10). We met Mr, Mastison about 3 miles before we reached the place where the cow was stolen. We had previously appointed Mr. Yantis captain of our little band. Soon after we passed Mr. Mastison, the road leaves the river and passed over a ridge and then down into the valley again. As we were going down the hill into the valley I saw some wagons a few miles up the river. I pointed them out to the rest of the company. One other man saw them. The rest of the company could not see them and said they guessed we were mistaken. I told them I was certain I saw some wagons coming toward us and presumed they were Mr. Ward’s train that Mr. Mastison had told us was behind. We thought we saw a creature away down on the valley. We went toward it until we saw it was a black stump. We then commenced hunting for the tracks of the packers where they had gone from their camping place to the road believing that they had killed the cow. We soon found where their horses had been feeding through the night. Mr. Yantis soon hallowed from a thicket of willows “here Jones is the remains of your cow.” From the appearance of things the packers and Indians had killed the cow and jerked the meat and what they could not eat the packers had taken with them. There were two or three bony pieces left over the fire, the entrails, hide and head were thrown into a (Jones manuscript:11) pond of water nearby. We were all sorry then that we had not searched the Packer’s budget. I took the largest piece of meat and told them I would take it to camp. As we were going across the valley toward the road I saw the wagons again, the remainder of the company saw them this time. They were standing still and we thought they were moving although it was about two o’clock. Mr. Yantis said he would be glad to see Mr. Ward and he would go and see him and we might wait at the ford until he came up. Another man said he would go with Mr. Yantis. They turned their horses and rode in a hurry up the valley toward the wagons, while we rode slowly across the valley toward the road. The wagons were corralled in the road on a small ridge. We had reached the road and followed it a short distance when I heard some person hallo behind us. I looked around and saw Mr. Yantis and the other man riding toward us at full gallop, motioning to us to come to them. We knew that something was the matter and rode toward them as fast as possible. They told us that the cattle and wagons were all huddled up together that the Indians were riding around them whooping and hallowing and shouting at them, and we might possibly save some of their lives if we would hurry. We rode toward the wagons as fast as our animals could carry us. When we got nearly to them, we saw the Indians [driving?] two of the wagons down the hill into the willows. We feared we (Jones manuscript:12) were too late. About that time the mule I was riding fell down and threw me 12 or 15 feet headlong into the dust. I was not hurt by the fall. Mr. Yantis helped me fix my saddle. We rode up to within rifle shot of the wagons in the bushes. An Indian rode out of the bushes toward us in a very daring manner. Mr. Yantis dropped behind some bushes and slipped up close to the Indians, before the Indian saw him. He shot at the Indian. The Indian appeared to be severely wounded, wheeled his horse and dashed into the bushes. Several of our men shot at the Indian and the Indians shot at us. One ball passed close by my head. A young man a few feet to my right received two balls almost at the same time. He staggered back a few feet and fell. I asked him if he was badly hurt, he said “Do not leave me.” I saw he was dying. he was a fine respectable young man, his name was Ames. He was the eldest son and main dependence of a poor widow. They were going to the Willamette Valley. When the man fell, three of our company mounted their horses and left the remaining three of us to fight the Indians alone. We hailed to them to come back and not leave us but they rode out of shooting distance and stopped. I told the two men that we could do no good by staying there, and that I would not stay. I mounted my mule and rode to the two wagons on the hill, the whole company followed me. An awful sight met our eyes, dead and wounded Indians and whites were lying promiscuously scattered on the ground around the wagons. There was a wounded Frenchman sitting by a (Jones manuscript:13) wagon, he could talk as strong and rational as ever he could. He begged us to take him along with us, We told him we could not take him since he was not able to ride a horse, he then begged of us to give him some water, but we had none to give him. Mr. Ward’s youngest son was also wounded and sitting up by a wagon. When Mr. Yantis approached him he reached out his hand and shook hands with him and said “Mr, Yantis we have been lying by waiting for you, we thought you were behind. He said he thought he could ride on horseback and some agreed to take him with us. When we attacked the Indians by the wagons in the bushes we could hear the women screaming I thought at the time that the Indians were torturing them or they were calling to us to release them. I was afraid of both. The horse that the young man rode, who was killed was left with his body and fell prey to the Indians. There were 4 or 5 yoke of oxen hitched together standing by the wagon on the hill. Bedding, clothing, provisions, and broken guns scattered over the ground. Some of the men were dead and some dying. I saw three young men lying together two were dead, the other was breathing. He heard me speak, opened his death struck eyes and looked wishfully in my face. I imagined he wanted to ask me to help him, but had not strength to talk. We did not see any women or small children, they had been taken into the brush. It was nearly night and we knew that we could not whip fifty Indians (the wounded boy said he thought there were about that number) and so we left the field of battle, started at a lively walk (Jones manuscript:14) for our wagons. We did not hurry our horses when we left for two reasons, one was that our animals could not stand it to be ridden fast, and the other was, the Indians would think we were afraid of them and follow us. Riding gave the wounded boy great pain, the loss of blood made him very thirsty. We had to stop several times and give him drink. We kept a sharp lookout in every thicket we passed through expecting the Indians would ambush us. I had the dysentery very bad that day and was unfit for such a trip. I took the wounded boy on behind me when we first started from the battle ground but I soon found I was too weak to take him as he hung very heavily on me and so I got Mr. Neily a very large stout man to take him. About dark we came up to Mr Mastison’s wagon. He had given up overtaking out train that day and camped for the night. The wounded boy we had with us was a nephew of Mr. Mastison. Ward’s wife was Mastison’s sister. He also had another sister in the train. He wept like a child when he learned the fate of his sisters. Mrs. Mastison fixed a good comfortable bed for her little nephew in her wagon. She gave me a good cup of coffee which revived me very much. We told Mr. Mastison we would help him hitch up his team and go on and overtake our train that night, as we thought he was not safe there. Soon after we got started with Mr. Mastison we saw a great light back at the battleground. We knew the Indians were burning the wagons and we feared the women and children also. We did not get to our train until about 2 o’clock AM. The captain promised (Jones manuscript:15) us we left in the morning, that he would not drive far that day but he drove all day hard and did not stop until he got to Fort Boise. There was a quack doctor in our train, he dressed the boy’s wounds. He was wounded in his side with an arrow and had his head badly bruised with a club or something of the kind, but he soon got able to be about. We wanted now if possible to raise a force sufficient to get the women and children from the Indians should they be alive. There were two large trains about one day ahead of us, Noble and Ball. A Young man that belonged at the Ferry at Fort Boise went out and got some help from those trains (Jones manuscript:16)

Aug 21 -- We corralled our wagons near the fort and made preparations to go the next day and fight the Indians (Jones manuscript:16).

Aug 22 - We succeeded in raising a mounted band of 20 men well armed and still had enough left to guard the wagons. I stayed with my family as my wife was unwilling to have me go. Old Mr. Grant from Soda Springs with his family and some Indians came riding up in the evening. We saw them in the distance we thought they were Indians coming to fight us. We made all preparations for a battle but we were badly fooled to find it otherwise (Jones manuscript:16).

Aug 23 - Early in the morning the little army returned. They gave us a salute of guns as they rode up. Everyone ran to hear the news. They said they did not find any of the Indians, they had gone to the mountains. They had (Jones manuscript:16) murdered the women and children in the cruelest manner. They found young Miss Ward where we left the Indians in the bushes. She was a beautiful and highly respected young lady 16 years old. The Indians had, from appearances tried to commit rape upon her and she had resisted. They had become angry and killed her by running irons up her womb they had left an iron in her. They had started with old Mrs. Ward and her three youngest children and Mrs. White to cross Boise River to their encampment. They killed Mrs. White before they got there by cutting and pounding her and then threw her into a pond-hole. Mrs. White was on her way to her husband in Oregon. Old Mrs. Ward and her three children they took to their camp and had a War dance over them, they built a fire and took the children by their hair and held them in the fire before their mother’s eyes. The Indians had burned off as much of the lower part of the children as they could without burning their own hands and left the remainder lying there. They had murdered old Mrs. Ward in a slow and cruel manner by cutting and burning her. She expected to be confined in about a month, she was the mother of a large family. The murdered Frenchman had crawled several rods from the wagons but was dead when they found him. The rest of the men were lying where we left them, their pockets had been rifled, otherwise, they had not been molested excepting that the Indians had emptied the feather beds on the ground and set fire to the feathers and as some of the bodies were under the feathers they got blackened by the fire (Jones manuscript:17).

The Indians had partly burned three of the wagons and left the others uninjured. Our men buried the bodies as well as they could, they had nothing to dig with but a small fire shovel. They found and buried nine men, three women and three children. As soon as the returned volunteers had told their tale and eaten the breakfast we commenced crossing Snake River. We swam the cattle and ferried our wagons. It is a wide dangerous stream to swim cattle across, but ours all got across safely. About 4 o’clock PM a large band of Nez Perce Indian came to salute the fort. They were painted very nicely and rode handsome horses. They rode around the fort and as many of our wagons as had not crossed the River, in single file yelling with all their strength and firing guns. They looked very nice and gave a good salute for a band of savages (Jones manuscript:18).

Snake River crossing $6 per wagon. Swam cattle (Jones manuscript:21).

WARD OUTFIT From Johnson County Missouri, leaving From Johnson County Missouri, leaving there 1854 March 20 (Ward in Gregg 1950:43).

About 20 persons in all (Masterson in Barton 1990:960. Masterson Family Traveled with Yantis Party in the forepart of the journey. At time of massacre, these 3 people were 4 miles ahead with the cattle. (Barton 1990:97).

Masterson, James Alfred [1850] Born 1827 Oct 4, Logan County Kentucky, son of Lazarus Masterson and Elizabeth Givens (Barton 1990:93,222).

Married 1. Vilinda H. Campbell 1854 April 6, Missouri

2. Martha Ann Gay 1871 Aug 27 Lane County Oregon (Barton 1990:222). Died 1908 Sept 11 Cour d’Alene Idaho. Buried Forest Cemetery, Cour d’ Alene (Barton 1990: 222).

Masterson, Vilinda H. Campbell Born 1837 Aug 10, Lafayette County Missouri, daughter of Henry Campbell and Nancy W. Ashburn (Barton 1990:222). Died 1870 Feb 20, Waconda, Marion County Oregon near Salem of TB. Buried Bell Passi Cemetery Woodburn Oregon (Barton 1990:93,98,222).

Masterson, Robert Brother of Alfred Masterson, Margaret Masterson Ward and Eliza Masterson White (Barton 1990:93). Son of Lazarus Masterson and Elizabeth Givens(Barton 1990:222).

Single (Barton 1990:93). The presence of this brother was not mentioned by Jones. If Masterson is accurate in placing him here, then he must have been young enough that Jones passed over mentioning him. Masterson is the only reference to him seen so far. Ward Family From Johnson County, Missouri (Bird 1934:81). If the Mastersons traveled with Yantis Party in fore part of journey (Jones manuscript:10), then Ward family may also have done so. One ox team of 6 yoke and two teams of 4 yoke.

Ward, Alexander, age 44 Son of David Ward and first wife (IGS #570). Killed 1854 Aug 20 in Ward Massacre near Middleton, Canyon County Idaho (Gregg 1950:48).

Ward, Margaret Masterson, age 37 Daughter of Lazarus Masterson and Elizabeth Givens (Barton 1990:222). Killed 1854 Aug 20 in Ward Massacre near Middleton, Canyon County Idaho (Gregg 1950:48).

Ward, children of Alexander Ward and Margaret Masterson: 5 children were killed during the massacre, 2 children were taken by Indians and died later and William and Newton survived (Masterson in Barton 1990:98). Six children killed at massacre sites (Gregg 1950:48); probably not true.

Mary, age 18 Killed 1854 Aug 20 in Ward Massacre near Middleton, Canyon County Idaho (Gregg 1950:48).

William Ward - Survived Grave Site William Masterson Picture below

Birth: Dec. 18, 1813

Lincoln County Kentucky, USA

Death: Oct. 13, 1890

Sodaville Linn County Oregon, USA

William A. Masterson was the third child of Lazareth Masterson and Elizabeth (Givens) Masterson. He married Eliza Jane (Violet) Masterson in 1840 in Missouri. They had 11 children.

While their parents and some siblings stayed in Missouri, William and Eliza Jane, with their children, and at least five of William's siblings and their children traveling separately or together, left Missouri for a new life out west.

In Canyon County, Idaho, two of William's sisters, Margaret (Masterson) Ward and Elizabeth (Masterson) White, with their husbands and their children, were traveling to meet up with other Masterson siblings in Oregon, including William and Eliza Jane, who were waiting for them in Lane County. The Ward and White families were traveling in a wagon train being led by Margaret (Masterson) Ward's husband Alexander Ward when they were attacked by hostile Indians. This became known as the "Ward Family Massacre." William's two nephews, the teenage sons of Alexander and Margaret (Masterson) Ward, were the only survivors. The two boys lived with William and Eliza Jane Masterson in Oregon until the boys reached adulthood.

William Masterson was a millwright by trade and built the Eagle Mills in Ashland and many other mills in Lane County, Oregon.

After living in Lane County, most of William and Eliza Jane Masterson's children eventually settled in eastern Oregon or in Idaho.

William Masterson was a contemporary of Rev. Jacob Gillespie. The Mastersons were present at the first church service that Rev. Gillespie preached in Lane County.

William Alexander Masterson died at Soda Springs in Douglas County, Oregon. Eliza Jane (Violet) Masterson survived her husband by 15 years, passing away in Elgin, Union County, Oregon on November 23, 1905. She is buried in the Elgin City Cemetery.

Robert, age 16 Oldest son (Ward in Gregg 1950:43). Killed 1854 Aug 20 in Ward Massacre near Middleton, Canyon County Idaho (Gregg 1950:48).

Newton - age about 13 (Bird 1934:82). Shot by an arrow (Ward in Gregg 1950:44). Taken to Oregon by Yantis Party (Johnson County, Mo)

William M., age 11 (Gregg 1950:430. Shot by arrow through left lung and side. Made his way to Fort Boise. After weeks recuperation, went on to Oregon with last wagon company of 1854 season. The family provided spring wagon for him for which they charged $1/day. Outraged citizens of Portland took up a collection to pay the bill (Gregg 1950:44).

Edward, age 9 Killed 1854 Aug 20 in Ward Massacre near Middleton, Canyon County Idaho (Gregg 1950:48).

Francis, age 7 Killed 1854 Aug 20 in Ward Massacre near Middleton, Canyon County Idaho (Gregg 1950:48).

John Apparently a younger child, taken by the Indians. Never found.

Flora, age 5 Killed 1854 Aug 20 in Ward Massacre near Middleton, Canyon County Idaho (Gregg 1950:48).

Susan, age 3 Killed 1854 Aug 20 in Ward Massacre near Middleton, Canyon County Idaho (Gregg 1950:48

Early Wagon Migrations 1845 - Allowances

Supplied by West Central Genealogical Society Transcribed for the WWW by M. Antal(c) 1999 The following list is what each person was allowed to take with them in the early wagon-train migrations: Per Person: 150 lbs. Flour or hard bread 25 lbs. Bacon 10 lbs. Rice 15 lbs. Coffee 2 lbs. Tea 25 lbs. Sugar 1/2 bushel dried peas 1/2 bushel dried fruit 2 lbs. Soleratus (baking soda) 10 lbs. Salt 1/2 bushel cornmeal 1/2 bushel corn Small keg of vinegar Pepper. CLOTHING PER PERSON: MEN - 2 wool shirts 2 undershirts WOMEN - 2 wool dresses BOTH - 2 pair drawers 4 pair wool socks 2 pair cotton socks 4 colored handkerchiefs 1 pair boots and shoes Poncho Broad-brimmed hat COOKING: Baking pan - used for baking and for roasting coffee. Mess pan - wrought iron or tin 2 churns - one for sweet, 1 for sour milk 1 coffee pot 1 coffee mill Tin cup with handle, 1 tine plate, knives, forks, spoons per person MISCELLANEOUS PER FAMILY: Rifle - ball - powder 8 to 10 gallon keg for water 1 ax 1 hatchet 1 spade 2 or 3 augers 1 hand saw 1 ship or cross cut saw 1 plow mold At least 2 ropes Mallet for driving picket pins SEWING SUPPLIES: (place in buckskin or stout cloth bag) Stout linen thread Large needles - thimble Bit of bee's wax Few buttons - buckskin for patching Paper of pins PERSONAL ITEMS: 1 comb and brush, 2 tooth brushes, 1 pound Castile Soap 1 belt knife - 1 flint stone per man PADDING PER PERSON: 1 canvas, 2 blankets, 1 pillow, 1 tent per family MEDICAL SUPPLIES: Iron rust, rum and cognac (both for dysentery), calomel, Quinine for ague, epsom salts for fever, castor oil capsules Camp Kettle, fry pan, and wooden bucket for water.

Life and Death on the Oregon Trail

Provisions for births and lethal circumstances

The Overlanders encountered their first hardship before they even left home

In December of 1847, Loren Hastings was walking the stump-filled, muddy streets of Portland, Oregon, when he chanced upon a friend he had known back in Illinois. Hastings had made the trip on the Oregon Trail unscathed, while his friend had lost his wife. Hastings' summary of their feelings was eloquent: "I look back upon the long, dangerous and precarious emigrant road with a degree of romance and pleasure; but to others, it is the graveyard of their friends."

The overlanders encountered their first hardship before they even left home, as leaving friends and family behind was difficult. Henry Garrison described his uncle's parting from Iowa: "When Grandmother learned the next morning that they were then on their way, she kneeled down and prayed that God would guard and protect them on their perilous journey." She would never see them again.

Covered wagons dominated traffic on the Oregon Trail. The Independence-style wagon was typically about 11 feet long, 4 feet wide, and 2 feet deep, with bows of hardwood supporting a bonnet that rose about 5 feet above the wagon bed. With only one set of springs under the driver's seat and none on the axles, nearly everyone walked along with their herds of cattle and sheep.

Emigrants banded together into parties or companies for mutual assistance and protection. Parties usually consisted of relatives or persons from the same hometown traveling together. In some cases, they formed joint-stock companies, such as the Boston and Newton Joint Stock Association, Iron City Telegraph Company, Wild Rovers, and the Peoria Pioneers.

The organization was required to ensure a successful journey. The most successful groups had a written constitution, code, resolutions, or by-laws to which the emigrants could refer when disagreements threatened to get out of hand. Almost all wagon trains had regulations of some sort, and rare was the group that didn't elect or otherwise appoint officers. The regulations typically included rules for camping and marching and restrictions on gambling and drinking. There were penalties for infractions, social security for the sick or bereaved, and provisions established for the disposition of shares of deceased members of a party.

A typical day started before dawn with breakfast of coffee, bacon, and dry bread. The bedding was secured and wagon repacked in time to get underway by seven o'clock. At noon, they stopped for a cold meal of coffee, beans, and bacon or buffalo prepared that morning. Then back on the road again. Around five in the afternoon, after traveling an average of fifteen miles, they circled the wagons for the evening. The men secured the animals and made repairs while women cooked a hot meal of tea and boiled rice with dried beef or codfish.

Evening activities included schooling the children, singing and dancing, and telling stories around the campfire. Some trains insisted on stopping every Sunday, while others reserved only Sunday morning for religious activities and pushed on during the afternoon. Resting on Sundays, in addition to giving the oxen and other animals a needed break, also gave the women of the wagon train a chance to tend to their domestic chores -- particularly doing the laundry, as the dust on the Trail pervaded every article of clothing exposed to it. Occasionally, a wagon train's arrival at a source of clean water was enough to prompt a special stopover for laundry day.

Marriages and births were always special occasions, and there were a surprising number of both on the Oregon Trail. Weddings were common either at the jumping off spots or, for those romances that bloomed along the Trail, on the Platte River or at Fort Laramie. A tongue-in-cheek conspiracy against the privacy of newlyweds by older-weds was called a "shivaree." Virtually every train had expectant mothers, and their newborns were often named for natural features, events, or important days. There is one story of an orphaned baby who was passed from breast to breast to be fed.

Leaving behind keepsakes, heirlooms, or wedding gifts was a painful reality many emigrants had to eventually face. Articles too precious to leave behind in the East were later abandoned along the trail to spare weary oxen. Hard stretches of the trail were littered with piles of "leeverites" -- items the emigrants had to "leave'er right here" to lighten their wagons. In later years, the Mormons made a cottage industry of salvaging the leeverites and selling them back to emigrants passing through the Salt Lake Valley. This practice, while arguably displaying an enviable entrepreneurial spirit, engendered further ill will between Mormons and Gentiles.

The tiring pace of the journey -- fifteen miles a day, almost always on foot -- got to many an emigrant. Elizabeth Markham went insane along the Snake River, announcing to her family that she was not proceeding any farther. Her husband was forced to take the wagons and children and leave her behind, though he later sent their son back to retrieve her. When she returned on her own, her husband was informed that she had clubbed their son to death with a rock. He raced back to retrieve the boy, who was still clinging to life, and on his return found that his wife had taken advantage of his absence to set fire to one of the family's wagons.

Perils along the way caused many would-be emigrants to turn back. Weather-related dangers included thunderstorms, lethally large hailstones, lightning, tornadoes, and high winds. The intense heat of the deserts caused the wood to shrink, and wagon wheels had to be soaked in rivers at night to keep their iron rims from rolling right off during the day. The dust on the trail itself could be two or three inches deep and as fine as flour. Ox shoes fell off and hooves split, to be cured with hot tar. The emigrants' lips blistered and split in the dry air, and their only remedy was to rub axle grease on their lips. River crossings were often dangerous: even if the current was slow and the water shallow, wagon wheels could be damaged by unseen rocks or become mired in the muddy bottom. If dust or mud didn't slow the wagons, stampedes of domestic herd animals or wild buffalo often would.

Nearly one in ten who set off on the Oregon Trail did not survive. The two biggest causes of death were disease and accidents. The disease with the worst reputation was Asiatic cholera, known as the "unseen destroyer." Cholera crept silently, caused by unsanitary conditions: people camped amid garbage left by previous parties, picked up the disease, and then went about spreading it, themselves. People in good spirits in the morning could be in agony by noon and dead by evening. Symptoms started with a stomachache that grew to intense pain within minutes. Then came diarrhea and vomiting that quickly dehydrated the victim. Within hours the skin was wrinkling and turning blue. If death did not occur within the first 12 to 24 hours, the victim usually recovered. One of this author's relatives, Martha Freel, came to Oregon in 1852. A letter sent home to an aunt in Iowa from Ash Hollow is now in my possession:

"First of all I would mention the sickness we have had and I am sorry to say the deaths. First of all Francis Freel died June 4, 1852, and Maria Freel followed the 6th, next came Polly Casner who died the 9th and LaFayette Freel soon followed, he died the 10th, Elizabeth Freel, wife of Amos [and Martha's mother] died the 11th, and her baby died the 17th. You see we have lost 7 persons in a few short days, all died of Cholera." - Martha Freel, June 23, 1852

The cholera outbreak along the Oregon Trail was part of a worldwide pandemic which began in Bengal. Cities throughout the United States were struck, and the disease reached the overland emigrants by traveling up the Mississippi River from New Orleans. The epidemic thrived in the unsanitary conditions along the Trail, peaking in 1850 as it was stoked by the immense numbers of prospectors and would-be gold miners on the overland trails in 1849 and '50. Adults originating from Missouri seemed to be most vulnerable to the disease. Fortunately, it was prevalent on the Great Plains, and once past Fort Laramie, overlanders were largely safe from cholera at the higher elevations.

Accidents were caused by negligence, exhaustion, guns, animals, and the weather. Shootings were common, but murders were rare -- one usually shot oneself, a friend, or perhaps one of the draft animals when a gun discharged accidentally. Shootings, drownings, being crushed by wagon wheels, and injuries from handling domestic animals were the biggest accidental killers on the Trail. Any one of these four causes of death claimed more lives than were lost to sharp instruments, falling objects, rattlesnakes, buffalo hunts, hail, lightning, and other calamities.

Deaths along the trail, especially among young children and mothers in childbirth, were the most heart-rending of hardships:

"Mr. Harvey's young little boy Richard 8 years old went to git in the waggon and fel from the tung. The wheals run over him and mashed his head and Kil him Ston dead he never moved." - Absolom Harden, 1847

Starvation often threatened emigrants, but it usually only killed their draft animals and thinned the herds they drove west:

"Counted 150 dead oxen. It is difficult to find a camping ground destitute of carcasses." - J.G. Bruff, 1849

"Looked starvation in the face. I have seen men on passing an animal that has starved to death on the plains, stop and cut out a steak, roast and eat it and call it delicious." - Clark Thompson, 1850

Patty Reed, an eight-year-old member of the Donner-Reed Party of 1846 recalled how her mother "took the ox hide we had used for a roof and boiled it for us to eat" when the party was stranded by an early snowfall in the high Sierras. Thirty-five members of the party died, and many of the 47 survivors ate their own dead.

Looking back from the Twentieth Century, it is clear that Indians were usually among the least of the emigrants' problems, though the overlanders certainly thought otherwise at the time. Tales of hostile encounters far overshadowed actual incidents, and relations between emigrants and Indians were further complicated by trigger-happy emigrants who shot at Indians for target practice. A few massacres were highly publicized, further reinforcing the myth. The Ward Train, for instance, was attacked by Shoshones who tortured and murdered nineteen emigrants. One boy escaped with an arrow in his side.

The Oregon Trail is this nation's longest graveyard. Over a 25 year span, up to 65,000 deaths occurred along the western overland emigrant trails. If evenly spaced along the length of the Oregon Trail, there would be a grave every 50 yards from Missouri to Oregon City. Medicine kits the pioneers carried to treat diseases and wounds included patent medicine "physicking" pills, castor oil, rum or whiskey, peppermint oil, quinine for malaria, hartshorn for snakebite, citric acid for scurvy, opium, laudanum, morphine, calomel, and tincture of camphor. It's a wonder that only one in every ten emigrants died along the way.

Independence, Missouri

The queen city of the trails

Few towns its size can claim such a rich history.

Independence, Missouri, lies on the south bank of the Missouri River, near the western edge of the state and a few miles east of Kansas City. Few towns its size can claim such a rich history: the Missouri and Osage Indians originally claimed the area, followed by the Spanish and brief French tenure. It became American territory with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Lewis and Clark recorded in their journals that they stopped in 1804 to pick plums, raspberries, and wild apples at a site later identified as the location of Independence.

William Clark returned to the area late in 1808 and established Fort Osage. George Sibley became the Indian agent for the Osage Indian tribe and the first factor of the tribal fur trading post. The story is told that Indians would gather outside his window to hear his 15-year-old bride play the piano. The Sibleys also entertained such notable visitors as John James Audubon, Archduke Maximilian of Austria, Daniel Boone, Sacajawea, the Choteau brothers, and in 1819 the first steamboat to ply Missouri, the Western Engineer.

As the population grew, Missouri became a separate Territory in 1812. By 1820, there were enough settlers to warrant statehood, but because of Missouri's stance in favor of slavery, it took the Missouri Compromise of 1821 to attain it. The growing communities in the west were grouped together into Jackson County, named in honor of Andrew Jackson, the hero of the War of 1812 and future president. The community of Independence was named county seat over neighboring Westport and Kansas City.

Independence grew up around the building used for court sessions. In 1827, the town was platted and a log courthouse was constructed by slaves. The courthouse was used as a pig pen in the evenings and became thoroughly infested with fleas. The judge was forced to resort to bringing sheep into the courtroom before a session to clear out the fleas. A permanent solution to the flea problem came in 1829 with the construction of a brick courthouse in the town square. The City of Independence was incorporated in 1849, four years after Oregon City's incorporation under the Provisional Government.

Growth in western Missouri increased rapidly because of trade with Santa Fe. Before 1821, trade with the Mexican outpost was illegal. After Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, trade became legal and was actively encouraged by the authorities. William Becknell led the first legal trading expedition and thus won a place in history as the "Father of the Santa Fe Trail."

Originally, cloth and tools were obtained in St. Louis to trade in Santa Fe for furs, salt, and silver and hauled overland in Conestoga wagons. Within a few years, traders were paying to transport their wares to Independence by steamboat, where they were loaded onto wagons for the journey over the Santa Fe Trail. Like the emigrants of later years, the traders recognized that the riverboats could shave several days off their journey by allowing them to jump off farther west.

A brief but significant chapter in the history of Independence began in 1831 when Joseph Smith moved his Latter-Day Saints to the city. They prospered on their large farms, started the first local newspaper, and opened their own schools. Townspeople were afraid the Saints would take over and disliked their anti-slavery views. A mob wrecked the newspaper and tarred and feathered the printers. The Saints departed rapidly for nearby Clay County, but the local citizenry still considered them a problem and the governor eventually ordered them out of the state. They moved to Commerce, Illinois, and rechristened it Nauvoo.

The outfitters who had set up shop to cater to traders on the Santa Fe Trail made Independence a natural jumping-off spot for the Oregon Trail. There was a riverboat landing at Wayne City and a mule-drawn railroad link to Independence. Robert Weston -- blacksmith, wagonmaker, and future mayor -- went so far as to specialize in wagons for the Oregon Trail. Although he insisted that a "Weston Wagon Never Wears Out," few survived the trip to Oregon. Hiram Young, a slave who had purchased his own freedom by making ax handles and ox yokes, also made covered wagons for the overlanders. From 1841 to 1849, wagon trains headed to Oregon and California left from Independence Town Square and followed the Santa Fe Trail into Kansas. However, sandbars building up at the steamboat landing and a cholera epidemic in 1849 prompted emigrants to bypass Independence for Westport. Doing so also shaved 18 miles off the Trail -- a good days' travel -- and eliminated a river crossing, as well.

Famous residents of Independence include Jim Bridger, hunter, trapper, trader, and guide; William Quantrill, leader of a Confederate band of raiders during the Civil War; Frank and Jesse James, outlaws, bank and train robbers, and local heroes; and Harry S Truman, destined to become President of the United States and end World War II with the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Finally, it is interesting to note that it was predicted in the 1840s that the cities of Independence, Westport, and Kansas City would eventually merge into the great city of Centropolis, envisioned as the dominant metropolis of the area, much like Chicago or St. Louis. Today, Westport is part of Kansas City and Independence is its largest suburb.

Another account. August 20, 1854 Ward Massacre (Caldwell, Idaho) The day after the Lake Massacre (previous entry), the vanguard of the same large but dispersed wagon train to Oregon was about 25 miles southeast of Fort Boise on the Snake River Plain, just east of present-day Caldwell, Idaho, when a party of 30 Shoshones approached Alexander Ward's five-wagon train of 20 emigrants. One Indian tried to take a horse by force, threatening an emigrant with his weapon. The white man shot the Indian down, starting a slaughter. The Shoshones killed Ward and raped and tortured several women, killing some. They hung children by the hair over a blazing fire. One boy, 13-year-old Newton Ward, was shot with an arrow and left for dead. His 15-year-old brother, William, took an arrow through the lung but lived. He hid in the brush until the Indians left, then wandered for five days until he reached Fort Boise. While the massacre was taking place, a group of seven emigrants under Alex Yantis, backtracking in search of stray cows, saw the commotion. They rushed in and rescued Newton Ward, but the Shoshones killed one of them, a young man named Amens, in the process. Outnumbered, Yantis's party had to leave the few survivors to their fate while they raced to Fort Boise. When the Indians left, they took 46 cows and horses and more than $2,000 in money and property. A rescue party of 18 men arrived two days later, only to bury the mutilated bodies. In addition to Amens, the Shoshones killed 18 of Ward's party. Some Indians may have been wounded, but it is not known for sure.

Oregon Trail

Shoshone Indians

Shoshone Indians

Location and Marker information:

The highway marker is located at GPS coordinates 43 40.618' N, 116 36.518' W. The other markers are only about 75 yards into the park from the highway marker. The markers and park are on the north side of Lincoln Rd, 0.2 miles east of Middleton Rd. and 1 mile north of Hwy 20, 26, approximately 2.5 miles east of I 84, Exit 29 in Caldwell. The site is approximately twenty miles west of Boise and about two miles south of Middleton. The marker is on page 35 of the publication "Idaho Highway Historical Marker Guide", go here for information and to purchase this guide.

Alexander Ward (b. 1813, d. August 20, 1854)

Alexander Ward (son of David Ward and Nancy Turk Mitchell) was born 1813 in Newport, Cocke County, Tennessee,

and died August 20, 1854, in Canyon County, Idaho. He married Margaret R. Masterson on March 05, 1835, in Lexington,

Missouri, daughter of Lazarus Masterson and Elizabeth (Betsy) Givens.

Notes for Alexander Ward: More About ALEXANDER WARD: Fact: While part of a wagon train on the way to Oregon, he was killed by Indians about 25 miles from Ft. Boise, Idaho. This horrible event was called the "Snake River Massacre", and is also known as the "Ward Massacre." In April 1854 Alexander Ward, Wife Margaret Masterson, and eight children left Missouri, Joined a wagon train and headed for Oregon. On August 20, 1854, the family was massacred by Snake Indians. Only two children survived, William and Newton Ward. More About Alexander Ward and Margaret R. Masterson: Marriage: March 05, 1835, Lexington, Missouri. Children of Alexander Ward and Margaret R. Masterson are: Mary E. Ward, b. 1837, Lexington, Lafayette County, Missouri, d. August 20, 1854, Canyon County, Idaho. George Ward, b. 1838, Lexington, Lafayette County, Missouri, d. August 20, 1854, Canyon County, Idaho. +William Mitchell Ward, b. April 29, 1839, Lexington, Lafayette County, Missouri, d. July 01, 1925, Yountville, California. +Newton Jasper Ward, b. March 04, 1841, Lexington, Lafayette County, Missouri, Notes for Alexander Ward: More About ALEXANDER WARD: Fact: While part of a wagon train on the way to Oregon, he was killed by Indians about 25 miles from Ft. Boise, Idaho. This horrible event was called the "Snake River Massacre", and is also known as the "Ward Massacre." In April 1854 Alexander Ward, Wife Margaret Masterson, and eight children left Missouri, Joined a wagon train and headed for Oregon. On August 20, 1854, the family was massacred by Snake Indians. Only two children survived, William and Newton Ward. More About Alexander Ward and Margaret R. Masterson: Marriage: March 05, 1835, Lexington, Missouri. Children of Alexander Ward and Margaret R. Masterson are: Mary E. Ward, b. 1837, Lexington, Lafayette County, Missouri, d. August 20, 1854, Canyon County, Idaho. George Ward, b. 1838, Lexington, Lafayette County, Missouri, d. August 20, 1854, Canyon County, Idaho. +William Mitchell Ward, b. April 29, 1839, Lexington, Lafayette County, Missouri, d. July 01, 1925, Yountville, California. +Newton Jasper Ward, b. March 04, 1841, Lexington, Lafayette County, Missouri,

d. September 03, 1925, Pateros, Okanogan County, Washington. Edward L. Ward, b. 1843, Johson County, Missouri, d. August 20, 1854, Canyon County, Idaho. Flora A. Ward, b. 1847, Johson County, Missouri, d. August 20, 1854, Canyon County, Idaho. Thomas C. Ward, b. 1848, Johson County, Missouri, d. August 20, 1854, Canyon County, Idaho. Susan F. Ward, b. 1850, Johson County, Missouri, d. August 20, 1854, Canyon County, Idaho.

Snake Indians - Testing Bows

1858-1860

Watercolor on Paper

|

.jpg)