|

| Blind Boone's home in Kansas City, MO. 912 Park Avenue |

|

| The vibrant image, painted by local Columbia artist David Spear, is titled “Tribute to Blind Boone. |

Lived on East Mill Street

Born: May 17, 1864

Died: October 4, 1927 in the home of his brother, Samuel Hendrix in the backyard at 408 Market St, Warrensburg, MO

Often overlooked by ragtime historians, John William "Blind" Boone had a remarkably successful and influential music career that endured for almost fifty years. Blind Boone: Missouri's Ragtime Pioneer provides the first full account of the Missouri-born musician's amazing story of overcoming the odds.

Boone's background and his approach to music contributed to his ability to bridge gaps--gaps between blacks and whites and gaps between popular and classical music. Boone's thousands of performances from 1879 to 1927 brought blacks and whites into the same concert halls as he played a mixture of popular and classical tunes. A pioneer of ragtime music, Boone was the first performer to give the musical style legitimacy by bringing it to the concert stage.

The mulatto child of a former slave and a Union soldier, Boone was born in Miami, Missouri, in 1864 amid the chaos of the Civil War. At six months he was diagnosed with "brain fever." Doctors, believing they were performing a lifesaving procedure, removed Boone's eyes and sewed his eyelids shut.

Despite blindness and poverty, Boone was a fun-loving, cheerful child. Growing up in Warrensburg, Missouri, he played freely with both black and white children, undaunted by racial differences or his own disabilities. He exhibited a keen ear and musical promise early in life; at only five years of age he recruited older boys and formed a band.

Recognizing Boone's talent, the town's prominent citizens sent him to the St. Louis School for the Blind. There he excelled at music and amazed his instructors. However, Boone became increasingly unhappy with the school's treatment of him and he frequently ran away to the tenderloin district of the city, where he first experienced ragtime. As a result of his forays, he was expelled after only two and a half years.

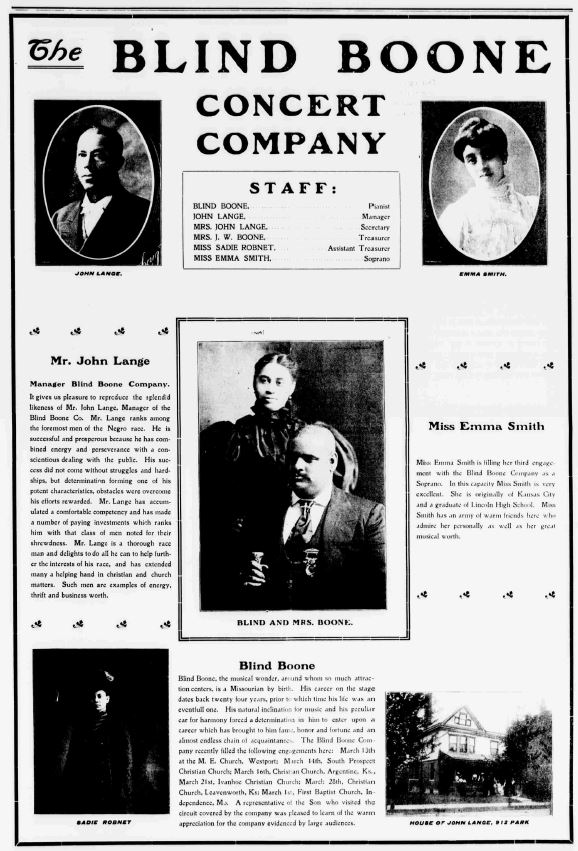

After some harrowing experiences, Boone met John Lange Jr., a benevolent black contractor and philanthropist in Columbia, Missouri. Boone and Lange began a lifelong friendship, which developed from their partnership in the Blind Boone Concert Company. Although the two experienced hardships and racism, fires and train wrecks, Lange's guidance and Boone's talent secured 8,650 concerts in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Blind Boone: Missouri's Ragtime Pioneer offers an engaging and readable account of the personal and professional life of Blind Boone. This book will appeal to the general reader as well as anyone interested in African American studies or music history.Link

AUTHORS/EDITORS

Jack A. Batterson received a Master's degree in Music History from the University of Missouri-Columbia and a Master's degree in Library Science from Indiana University in Bloomington.

Born

Tue, 1864-05-17

John William “Blind” Boone was born on this date in 1864. He was an African American musician.

Born at a federal army camp near Miami, Missouri, his mother, Rachel, was a runaway slave who had taken refuge with the regiment of the Union Army as a cook. The descendants of pioneer Daniel Boone owned her. The regiment's bugler fathered the child, but they were never to know each other. Shortly after Boone was born, his mother moved to Warrensburg, Missouri where she earned a living by cleaning the homes of prominent families. At six months of age, the Young Boone became very ill with "brain fever."

Only a very radical surgical procedure offered a chance to save the child's life releasing pressure from the swelling of the brain. There was one way to accomplish that, by surgical removal of the eyes. The operation was performed. John William lost his sight, but not his very extensive intelligence. Greatly loved, John William was a happy, musically gifted child. At age three, he was capable of beating out rhythms. He had a tin whistle at age five with which he could play tunes and imitate sounds in nature like birds. Soon John organized a band with instruments that included tin whistle, drum, and tambourine. Rachel sought ways to have John educated and succeeded in recruiting the town's assistance.

Warrenberg's city fathers purchased the railroad ticket that brought John William to the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis for two and one-half years. He quickly demonstrated his ability to reproduce on the piano any musical piece he heard. Despite his musical giftedness, the school was teaching him to make brooms. Driven to find outlets for his interests and talents, Boone would sneak out to the 'adult' area of town to hear the Ragtime piano. School officials finally expelled him from school but a conductor befriended and allowed him to ride the train home in exchange for entertaining passengers by playing his harmonica. In Warrensburg, Boone lived in the Black community for the first time in his life. Rachel had married widower Harrison Hendrix, the father of five, when John was eight years old. Wanderlust gripped him, however, and he strayed from home repeatedly at times, with regrettable consequences. The Christmas holidays of 1879 were to bring dramatic positive change to Boone’s life.

The gifted young musician was invited to participate in a festival at the Second Baptist Church in Columbia. The event was an annual gift to the community by a very successful builder and contractor, John Lange, Jr. Boone was invited back for a concert in March, 1880 one in which he was featured with a second sightless black pianist, Tom Bethune known as 'Blind Tom'. John William Boone's professional career was launched with the event and John Lange, Jr. took on the role of his manager.

Lange began by sending John William to Christian College in Columbia to further his musicianship introducing him to the European classical composers. Further, Lange's organizational skills were outstanding. To transcend the stigma of disability, Lange adapted the motto, "Merit, not sympathy, wins" for the J. W. Boone Music Co. To make significant Boone’s capacity to reproduce anything he heard, Lange made it known that one thousand dollars would be given to anyone who could stump him by playing something the artist could not play back accurately.

Boone and Lange never had to make good on the offer. Lang also hired advance men, who would travel to towns to advertise Boone's abilities and make the necessary arrangements prior to the arrival of the great man. His career peaked between 1885 and 1916, earning between $150 and $600 on their best nights. His company trained many young singers and music agents. By 1916, Boone toured US, Canada, and Mexico and (reportedly) England, Scotland and Wales but no documentation has yet been found for the overseas events.

Lange wrote about the period from 1880 to 1915 where they would travel 10 months each year, with 6 concerts per week, a total of 8, 650 concerts. Distance traveled averaged 20 miles per day or 216,000 miles and they slept in 8,250 beds. Boone played mainly in churches and concert halls and to segregated audiences. After he became popular, piano companies provided the pianos so he did not have to haul them by horse and wagon. He wore out 16 pianos by 1915. Boone married Lange's youngest sister in 1889 and never recovered from Lange's death in 1916.

He moved into a permanent home in Columbia Missouri, which is now on the national register. Besides a classical repertoire, Boone played plantation melodies, religious songs and Ragtime. He sang minstrel tunes/plantation songs, wrote and sang 'coon' songs as all Black performers did that came out of the minstrel stereotypes of earlier years. Religious songs included "Nearer My God to Thee" and others. In 1912, he was contacted by the QRS Piano Roll Company and became one of the first black artists to cut piano rolls. Boone gave generously to black churches and schools, and at one time he had had an income of $17,000 per year. Boone gave many benefit concerts to further Black schools and churches in the Columbia area. He was just 5 feet tall but was a very impressive figure. Because he could not walk without guidance, he frequently carried a child upon his shoulders as a navigator. He had an astounding memory and was called a walking encyclopedia.

Boone could tell a child's age by putting his hand upon a child's head. H e had a very happy and warm personality and children loved him. Boone also belonged to fraternal organizations, yet his only family was his wife and his mother Rachel who died in 1901. After 1920, competition from movies and radio made it very difficult to secure bookings. Boone did a final big tour in the East in 1919 and 1920. His last concert was on May 31, 1927. He died of a heart attack on October 4, 1927. The funeral was a major event in the black community in Columbia, Missouri.

Reference:

The African American Atlas

Black History & Culture an Illustrated Reference

by Molefi K. Asanta and Mark T. Mattson

Macmillam USA, Simon & Schuster, New York

ISBN 0-02-864984-2

The legendary ragtime pioneer John William Boone was born to Rachel Boone in 1864. census records have indicated a range of birth years from 1862 to 1866, but 1864 is the most accurate year of birth according to the author's research. Rachel was an escaped slave from Kentucky who found a position as a "contraband cook" for the Union Army in Miami, Missouri. A mulatto, she claimed to be an indirect descendant of famed American Daniel Boone, a claim with some measure of credibility, and kept that name. John's father was a white bugler with the Union Army.

Given that information, the Union Army records show only one bugler in an applicable at that time period, Private William S. Belcher of Company F of the 3rd Regiment, Missouri State Militia Cavalary, then later with the 7th Regiment in the same capacity as bugler. Not only was he in the Miami area around the probable time of conception, but further investigation into Army records reveal that he was on a furlough to Miami about the time of John's birth in 1864. The furlough turned into an attempt to enlist with the 23rd Missouri Infantry the day after John's birth, which turned into a desertion charge from the Union Army and a conviction. After the war he married and became a farmer. It is unclear if he ever had more than peripheral contact with his son for whatever reasons. Shortly after John's birth Rachel moved to Warrensburg, Missouri. She is shown there in 1870 working in washing and ironing, and was working for many prominent families in the area. Curiously, John, now called Willie, was shown as only 4 years old in that census, and he had another brother, Wyatt, father unknown, who is shown as 2 years old in 1870. When Willie was around 6 months (some sources claim 6 years) old he contracted what the doctors called "brain fever," most likely some form of meningitis by later accounts, and their cure was to have his eyes surgically removed to relieve the pressure,

At age 7 he received a French harp as a gift, quickly learning to tune and play it. This allowed him to earn some extra income, even before he was 8, playing it at various functions or in people's homes. When he was eight, Rachel ended her life as a single mother by marrying Harrison Hendrix, and eventually the couple added five more siblings to Willie's family. They moved to a one room cabin, but by all reports it was a loving household, and Willie remained close to his step-siblings throughout his life. In an effort to accommodate her son's needs, Rachel enrolled Willie at the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis, with the generous help of donations by neighbors and townspeople, both black and white. Some also funded the train trip, and made him clothes to take along. His blindness and pure joy in life helped make all of them color blind as well. He left Warrensburg in the fall of 1873. It was clear early on that Willie was not happy at the school, and instead of communing with his own classmates, he preferred to listen to older students practice in the music room. One of them, Enoch Donley, befriended Willie and taught him basics of technique, and also introduced him to a piano teacher at the school. After a year of work, Boone was able to play virtually anything he heard with commendable technique. The situation at the school changed within a couple of years, and a new supervisor was put in place, changing the way black students were treated. Willie was removed from most of his musical access and taught to make broom instead. In order to play he escaped the school at night (presumably with some assistance) and started hanging around the nearby tenderloin district where early forms of what would become ragtime were being performed. While he was able to pick up a lot from listening to the brothel and bar pianists, he was eventually caught enough times that he was expelled from the school. Forced to live on the streets, he played where he could, often in churches, and even sang to people in public places like train depots for money. Nearly starving, a conductor found him and managed to get him back to Warrensburg and his mother. Back home, Willie continued to play in homes, halls and churches. It was in a church where he was giving a small concert that John Lange, a local contractor and successful black businessman, first heard Boone play. He was substantially impressed, and after some time decided to expand his scope of business operations, becoming one of the first African American managers of a concert artist. In preparation for sending Willie out into the world, Lange sent him to Christian College in Columbia for advanced musical training with Anna Heuerman. It was here that he learned a great love for classical music, which he was quickly able to emulate, and even duplicate, sometimes on the first or second hearing. After sufficient training, Boone came home, and with Lange formed the Blind Boone Company, adopting the motto Merit, Not Sympathy, Wins. Based in Columbia, the pair set out to make Boone famous, with resounding results - albeit slowly resounding.

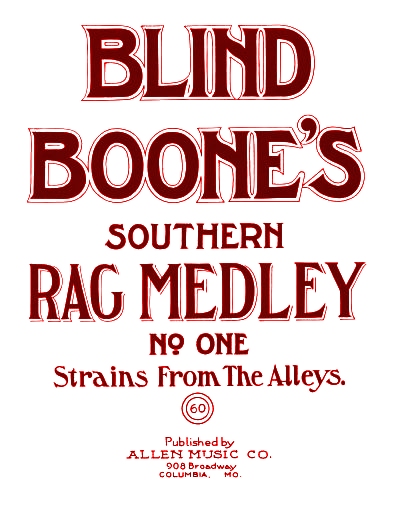

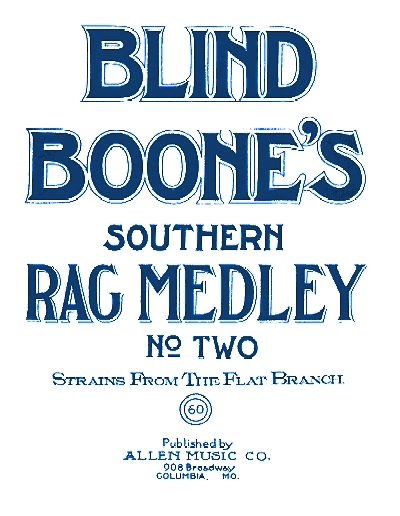

This was Boone's own pianistic representation of an F4 tornado that tore through Marshfield, Missouri on April 18, 1880, killing 99 people and injuring at least another 100. Descriptions of Boone's performance conjure up a tour de force of effects that potentially had a detrimental effect on the instrument, and it became his signature piece. Marshfield Tornado was never recorded or printed as Boone wanted it to be entirely his, each performance to be unique. In truth, it is questionable whether a player piano could have fared well with the onslaught of notes from Boone's hands. One newspaper described it as follows: The piece is a variation, beginning with the quiet of the Sabbath morning at church, the approaching storm and the roaring destruction as it sweeps over the town. The noise dies down and peace again reigns." The early years of the show were difficult, but necessary to build Boone's reputation. Lange, Boone, and perhaps a couple of other, traveled the Midwest in a wagon carrying a piano with them, allowing them to set up wherever they needed and avoid the reservations some white piano owners might have about the boy's taking over of their instrument. However, this was hard on the instrument physically, and part of the budget from the income was set aside for replacement pianos every few months. As Boone's reputation grew, it seems that a good piano was more readily available at their destinations, and eventually they did not have to travel with one. They also often stayed with a local sponsor to avoid hotel expenses, but the home base was in Columbia. In the June 1880 census, Boone is shown as one of many residents in the home of Columbia farmer Alfred Woods and his large family, although no profession is listed. As Boone and Lange grew their show, Lange would hire somebody to set out a week or more ahead of the troupe for public relation purposes, advertising the coming of Boone with posters and word of mouth. Notices in the paper comparing Boone with the already established "Blind" Wiggins didn't hurt either, such as this one with an off-handed sleight towards the older artist from the Gettysburg Compiler of June 9, 1885: "Poor Blind Tom, the alleged[!] pianist, is discovering that another black pianist, known as Blind Boone, but who Tom considers anything but a boon to him, is about to become a formidablee rival in concert business." While Blind Tom had his own niche and a considerable lock on Midwest concert halls, the report was more or less predictive. By the end of five years, when Boone was approaching 21, the company had no problem getting booked in towns or cities of every size. The reviews were positive and more money was also coming in, so Boone and company were living well by the time the 1890s came around. In 1891, John married Eugenia Lange, his manager's youngest sister. They remained together for the rest of his life. According to an article in a May 1893 edition of Kunkel's Musical Review, the Blind Boone Concert Company was in town for four weeks, and the star was greatly lauded. "His playing is remarkable, not because of his blindness, but because of his artistic excellence. John W. Boone is justly considered the successor of the celebrated [Louis Moreau] Gottschalk. He grasps with marvelous rapidity any composition played for him, and the most difficult pieces are played after single reading. His engagements here drew crowded houses nightly." The company also grew in size over the next decade, as Lange and Boone added vocalists to the show, including Emma Smith, Melissa Fuell, Marguerite Day, Stella May (just 16 when she was recruited) and Josephine Huggard. They also expanded their reach, performing at least 8,000 concerts in the United States between 1880 and 1895, along with performances in Canada, Mexico and Europe. One of Boone's greatest joys was sharing his gifts and enthusiasm with children. He would openly promote his desire for parents to bring their children to his performances in order to bring them to music, and would sometimes bring large groups of them inside the performance hall for free, simply so he could encourage them to also learn the thrill of playing and sharing that gift. It evidently effected a great many youths who ended up working hard to learn to play, some actually becoming fine pianists in churches or theaters. He often gave back to the church community that supported him, providing funds for a great many church and school building or repair projects wherever he went. According to the 1900 census, Boone was firmly ensconced in Columbia, and Eugenia was now the treasurer for the company. His mother Rachel died in January 1901. Throughout his career Boone had composed a number of number of songs, instrumentals and classically styled pieces, many that were eventually published, including some notable ones between 1900 and 1910. This included the beautiful Aurora Waltz of 1907, reportedly inspired by descriptions of the aurora borealis over the northern hemisphere. In 1908 and 1909 he contributed two medleys to the ragtime collective, largely made up of folk themes and some original derivatives. Blind Boone's Rag Medley Number One: "Strains from the Alleys", and Blind Boone's Rag Medley Number Two: "Strains from the Flat Branch", were not the same type of ragtime that many other composers had been writing by that time.

During his years as a prominent performer, his endorsement was sought out by certain piano companies, and in the end the Chickering Piano Company of Boston, Massachusetts, would offer him the biggest incentive of all. Chickering, perhaps Steinway's biggest U.S. rival at that time, offered him a large oak nine foot concert grand in 1891 which he enjoyed enormously. (It is now kept in the Boone County Historical Society in Columbia, Missouri, and can still be played.) They made several others for him over the years which he routinely wore out. However, his name did show up in connection with other instruments from time to time. Among those were Steinway and Estey, the latter being a famous organ builder as well. In The Music Trade Review of July 6, 1901, a letter of endorsement to Bush and Gerts was quoted: "The Bush & Gerts piano is a fine instrument, possessing a pure sweet tone, and any dealer may well be proud to handle such a piano. It is bound to make friends wherever it is known and sold." One month later on August 3, 1901, the following was printed in the MTR:

Carl Hoffmann, of Kansas City, Mo., is, and long has been, a Chickering enthusiast. The new model Chickering baby grand which he received last week, has, however, compelled more than the ordinary number of adjectives to express his approbation of its musical merits.

While testing this instrument, "Blind" Boone, a negro musician widely known throughout that section, strolled in and became so enamored with the Chickering grand that he purchased it, notwithstanding the fact that he already has several Chickering pianos in his possession. He knows a "good thing" without seeing it. It is said there are few better judges of tone than "Blind" Boone, and it does his judgment credit when he selects a Chickering.

In the case of many concert pianists, the highly-regarded Boone in partiular, it seems that any company that could encourage him to wax poetic on their instrument would exploit those words in their favor, in spite of his association with other companies. Another example is found in the May 28, 1910 MTR concerning the R.A. Rodesch player piano: "Blind Boone, who is one of the celebrated pianists of the West, visited our factory just before [President R.A. Rodesch] left and he was so delighted with what he saw and heard that he left an order for one of the players to be installed in his own piano." Yet another Chickering endorsement was printed on October 9, 1915, and it outlines some of his technique for learning new pieces:

— Uses the Chickering Grand for Concerts — Pianist Well Known in the West.

One of Boone's last endorsements was found in the February 1, 1919 MTR:

While at the Sonora music rooms he was furnished, at the request of the Plaza Theatre of that city, with a Kohler & Campbell piano, Style 8, to be used in conjunction with his program, before commencing which he paid the following tribute to the instrument: "I want to thank Mr. Stephenson for the splendid piano which he has so kindly furnished me with that I might be able to render this program. It is one of a rare make, has a beautiful tone, and it has a splendid action. You will find the Kohler & Campbell a remarkable instrument for the price, the base is excellent and any piano that stands my 'Marshfield Storm' is a good one."

Boone entered his fourth decade of concertizing in 1910. In late 1912 John recorded Rag Medley Number Two and six other tunes from his repertoire to piano rolls for the QRS Piano Roll Company on their Autograph series, one of the first black artists to do so. It is said (hard to verify) that on his recording of When You and I Were Young Maggie that he actually jammed or overloaded the recording mechanism because of the number of notes he was playing in rapid succession at great velocity. One of his favorite concert segments was asking somebody from the audience to play a piece he didn't know (and that was a limited list), after which he would sit down and play it back for them, something that impressed even the highest ranking musicians. It was clear that not only could play virtually anything in the classical style, but that he could also make it his own, infusing Afro-American rhythms and other tricks into the performances. While he didn't quite "rag" the pieces, he did give them a kick that most performers at that time were perhaps not as adept as excecuting.

By 1916 it was estimated that the Boone Company had played over 26,000 concerts in 36 years, suggesting many days where three or four performances were held. But that was perhaps the peak of his career, and his long-time friend and manager John Lange died that same year. The novelty had started to wear off, particularly with a world that was progressing ahead, a world that was at war, and a world that was looking for change. While vaudeville was still thriving in 1920, the beginning of the "jazz age," and movies were coming into their own, Boone's act was old hat by now. Without Lange the bookings diminished greatly and Boone, once flush with money, found himself and Eugenia struggling to make ends meet. In 1920 John and Eugenia are listed in Columbia with her as the head of household, and neither with an occupation listed. He continued to play sporadically over the next several years, but started to show signs of physical deterioration and other health issues. Yet the positive reviews kept appearing. One from September 8, 1924, from the Cape Girardeau Southeast Missourian stated that "Boone proved himself an artist of great versatality playing classical music with the grace and feeling of a true artist, interpreting folklore selections, and singing them with great drollness, and and whipping off ragtime selections with as much energy as would Paul Whiteman's best 'tickler over the ivories.'" In December 1925, the same paper reported Boone off on another seven month tour to "Illinois, Kansas, Oklahoma, Corlorado, New Mexico and California. The end was become inevitable, however. His final public concert was held on May 31, 1927 in Virden, Illinois, during which he announced his plans to retire. Boone's statement found its way into the papers in short order, as partially quoted here:

Blind Boone, negro pianist... brought his colorful concert career of 47 years to a close recently...

After completing a program before a large crowd, the aged musician announced the concert was his final appearance on tour and perhaps his final appearance fo all time. He will retire to Columbia, Mo., this summer and to recover his failing health. It is probable he will give further concerts on special occasions. Columbia was also the home of John [Lange], who for 36 years was Boone's manager. [Lange's] death is believed to have had a telling effect on Boone. In his last concert he was assisted by his niece, Miss Margaret Day, who sang many of his compositions, including "Keep On Till the Judgement." He also played his famous "Marshfield Tornado."... Blind Boone played many concerts in Kansas City, many of them in churches. Years ago one of his regular appearances here was at the old Lydia Avenue Christian church, Fifteenth st. and Lydia av. Always he impressed his audiences with his compositions, his technique, his remarkable memory and a huge watch... [He] would have a "children's program," producing his huge watch. Asked what time it was, he would press a stem and the watch would chime the quarter, half and full hours, to the delight of his juvenile auditors. It was [in Springfield, Illinois] in September, 1909, Boone first met Bert Williams, comedian. The musician called on the singer at the Shubert theater. Williams' dressing room is closed to many of his race, but he welcomed Blind Boone. Complements were mutual... "I feel fully repaid for my so-called affliction," Boone says. "I have music, friends, and am happy." Boone is a business man as well as a musician. His investments have been good. It is estimated his average annual income is about $17,000.

Another report the following week in The Afro American claimed he has earned some $350,000 during his career claiming he was worth that much, not accounting for the expenses of travel and life in general along the way. Even with such a high income his growing expenses and payment of debts kept the family from being flush. John W. Boone was felled by a fatal stroke and acute dilation of his heart while visiting his half-brother Harry in Warrensburg in October, 1927. In spite of the grand reports of his impressive income, Boone's estate was worth a mere $132.65. Eugenia was soon reportedly found to be insane, although any record of commitment is difficult to locate. There was not even enough money left to afford a proper marker for John's grave.

Fortunately the people of Columbia have since successfully resurrected the memory of Boone, forming the Blind Boone Memorial Foundation, Inc. in 1961. The Chickering oak grand was restored for a concert that same year by the Joplin Piano Company, and the first memorial concert was held using that instrument. They were responsible for marking his grave in 1971, and opening a museum dedicated to him and Missouri folk music. There is an annual ragtime festival held each June in Columbia, Missouri, named in Boones honor, in the grand Missouri theater. His last words speak well of his mission in life, which was most certainly accomplished wherever he went. "Blindness has not affected my disposition. Many times I regard it as a blessing, for had I not been blind, I would not have given the inspiration to the world that I have. I have shown that no matter how a person is afflicted, there is something that he can do that is worthwhile." He proved this beyond the shadow of any doubt, opening doors for a number of African-American artists and businessman through his generosity and extraordinary talent.

A great deal of this biography was extracted or assembled from public government records, school records, newspapers, periodicals and commonly known information about Boone. Some of the information was culled from Blind Boone: Missouri's Ragtime Pioneer by Jack A. Batterson with Rebecca B. Schroeder, available from many sellers including Amazon.com. Thanks also to the Blind Boone Ragtime Festival and Blind Boone Park in Warrensburg, Missouri, for their continuing efforts to keep Boone's memory and positive message of hope alive.

| |||||||||||||

Article Copyright© by the author, Bill Edwards. Research notes and sources available on request at ragpiano.com - click on Bill's head.

Southern Rag Medley #1 by Blind Boone

Little Known Black History Fact: Blind Boone, Musical Wonder

John William Boone was born on a federal camp in

|

| Blind Boone and wife Eugenia |

Miami, Missouri to Rachel Boone Hendricks, a runaway slave, who was owned by descendants of Daniel Boone. Once his mother moved to Warrensburg, Missouri, John was diagnosed with “brain fever” (which was later called cerebral meningitis). The only way his mother could save his life was to have his eyes removed. Baby John lost his sight, but not his intelligence.

His mother would provide him with musical instruments as a toddler, and he began making music at age 3. He imitated birds with a tin whistle and learned music tunes. It was only a matter of time before John Boone would start his own band. Recognizing his talent, the fathers of Warrensburg, Missouri got together and purchased a train ticket for John so he could study at the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis.

A gifted student, Boone wanted desperately to play music on the school’s piano, but they forced him to make brooms. He was taken on as a secret student by one of the older students and would play back music after only hearing it one time. One year, after returning from break, Boone found that the new superintendent banned blacks at the Missouri School for the Blind from playing the piano. So John Boone sought other ways to feed his love of music.

He would sneak out to the nightclubs in the adult part of town called the Tenderloin District. After being continuously absent, the school would finally expel him for his actions. Looking for a way home, a friend and train conductor would allow him to ride the train back in exchange for entertaining passengers on his harmonica. Once he returned, he was playing on the streets again, and came to be managed by swindler Mark Cromwell. Cromwell let Boone play, but refused to pay him the money. He even lost Boone in a gamble, and he was locked in a room for three days until Cromwell stole him back.

|

| Blind Boone at the Piano, Columbia, MO |

During a Christmas performance at church in 1897, John Boone’s life would change. He performed alongside another man named Blind Tom Bethune.

Once Entertainment Hall owner, John Lange Jr., saw Boone play, he signed on as his manager and sent him to college to study music. He then started the J.W. Boone Music Co. They funded the company by asking anyone to challenge Boone with a song – not knowing that he played from memory. The men toured overseas and gave six concerts a week. Now called Blind Boone, John married his manager’s sister and started a family.

When J. Lange passed, Blind Boone performed for charity, giving back to churches. Blind Boone died in 1927 from a heart attack and had one of the largest funerals in the black community of Columbia, Missouri.

Last years: Boone's career flourished during the 1890's when opera houses were the primary source for entertainment and, in particular, his type of variety show. However, around 1920 his career began to decline when the radio and movie theaters superseded the concert hall as the main source of entertainment. There was no longer a demand for his type of company. Furthermore, in 1916 Lange died, creating a decline in bookings and a decrease in finances. At Boone's death on October 4, 1927 Boone's estate amounted to only $132. His grave remained unmarked until 1971.

Boone's last words give insight into his character:

"Blindness has not affected my disposition. Many times I regard it as a blessing, for had I not been blind, I would not have given the inspiration to the world that I have. I have shown that no matter how a person is afflicted, there is something that he can do that is worthwhile."

Boone's presence on the concert stage paved the way for many African-American performers and made the music of African-Americans more accessible to the general public. In

this respect, he was a pioneer.

John W. "Blind" Boone - The ManNotes by Frank Townsell

Born in Miami, Missouri, on May 17, 1864, one year after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, John W. Boone ("Blind" Boone) became, during his lifetime, one of the most loved and respected musicians in America. His mother, Rachel Boone, had fled to freedom during the Civil War and worked, during the war, as a cook in an army camp in west-central Missouri. Rachel claimed to be among the numerous descendants of Daniel Boone and adopted the family name. John's father was a bugler about whom little is known.

Early years:Shortly after giving birth to her son, John, Rachel moved to Warrensburg, Missouri where she worked as a domestic for several prominent families. At the age of six months, John's eyes were removed to save his life due to "brain fever". According to later sources this was probably some form of meningitis.

In spite of his handicap, John led a happy, contented life and displayed early abilities for music. At the age of three, he was observed by neighbors singing and beating time on an old tin pan. At the age of seven someone gave him a French harp which he learned to play to earn money from the local residents. When he was eight, his mother married Harrison Hendrix who had five children and they moved to a one-room log cabin. Apparently it was a happy household because John remained close to his step-brothers and sisters throughout his life. About this time Rachel decided to enroll him in the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis. Donations were made by the local townspeople and in the fall of 1873 Boone left by train for St. Louis.

"Blind" Boone's musical genius is discovered:John did not like school very much and preferred to go to the music room to listen to the older students practice. Soon he was able to play easily the pieces that he heard and was befriended by a fellow student, Enoch Donley, who showed him some of the rudiments of piano technique. It was Donley who persuaded a piano teacher to listen to John. The teacher was very impressed and declared Boone a genius. Boone became proficient in his studies and in less than one year he was able to play any composition he heard. John Lange and "Blind" Boone John Lange and "Blind" Boone:Shortly afterwards, John met John Lange, a man who was to play an important role in the development of his musical career. Lange heard Boone play in a church concert and was so impressed that he offered to manage his career. Lange is also important as one of the first African-American managers of a concert artist. He was a successful businessman and had considerable influence in the black community.

Lange also saw to it that Boone developed his gifts to a greater extent by arranging further training. So Boone was sent to Christian College in Columbia, Missouri, where he studied the classics with Anna Heuerman and perfected his skills.

The first concert of the Boone Company under Lange's auspices was held on January 18th, 1880 at St. Paul's Methodist Church in Jefferson City, Missouri, and was a great artistic success. Boone played a Hungarian Rhapsody by Liszt and some Beethoven Sonatas as well as selections from operas, and a number of his own compositions including the famous "Marshfield Tornado", a piece for which he was to become famous. This piece was a musical representation of a tornado which actually happened in Marshfield, Missouri. According to his biographer, Boone refused to reproduce the piece, either by publication or piano roll, claiming that he wanted to reserve it for his own use. During this period Boone married Eugenia, Lange's sister, who frequently traveled with him on his tours.

Boone plays over 26,000 concerts:Thereafter, Boone became a highly successful concert artist, playing in thousands of concert halls and churches and earning an enormous income. By 1916 his company had played over 26,000 concerts throughout the world and Boone was described by his contemporaries and critics as a musical genius with a both a phenomenal musical ear and musical memory. One of his most remarkable feats was to ask a performer to come from the audience and play a piece which was unknown to him, after which he would repeat it exactly as performed. His reputation was so great that the Chickering Piano Company made a nine foot concert grand for his use exclusively. This impressive instrument was made entirely of oak and is now kept in the Boone County Historical Society at Columbia, Missouri where it is made available to visiting pianists.

Like his famous contemporary, Scott Joplin, Boone wrote music in a variety of styles, but whereas Joplin (whom he knew) was best known for his ragtime music, Boone was best known for his classical compositions although he also wrote and played ragtime music. Boone wrote waltzes, galops, polkas and caprices and infused them with African-American rhythms and melodies. One of his most famous compositions has, as its basis, the melody made famous by Stephen Foster - "Old Folks at Home". The ragtime pieces use indigenous folk tunes of Columbia and show his consummate knowledge of the genre, a knowledge developed from his school days in St. Louis.

|

| Blind Boone Home, Columbia, MO |

|

| Blind Boone |

Blind Boone Park was originally built for the black community during segregation. "Separate but Equal" was the cry of the day in 1954, and this park reflected that sentiment. The park could hardly be considered equal, but did include bathrooms with flush toilets and two BBQ grills. Interestingly enough, although the members of the black community were not welcome in the other parks in town, the black community was generous enough to invite members of the white community to enjoy music and other activities with them in Blind Boone Park. Music was a big part of the summers spent in the little park, with bands setting up on the grass to play and a plywood dance floor laid down for dancing. Kids could run and play while the adults cooked, danced and visited. A small "joint" serving BBQ was across the street from the park (at the "cave"). After segregation was over, the park held little interest. Although still used by some, many were understandably venturing out and exploring the freedoms allowed by law. The city was hardly proud of what the park symbolized and eventually maintenance was discontinued and the site grew up in weeds and brush. In June, 2000 the Blind Boone Park Renovation Group was formed and work began to renovate the park into a community park honoring it's history and the memory of John William "Blind" Boone. A diverse group of volunteers have worked together to make the dream a reality, giving pause to differences and getting to know one another. It is hoped that Blind Boone Park will reopen in Summer of 2004. A grant has been obtained from the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, State Historic Preservation & National Parks Dept. and money is being raised to match grant funds. Building has begun, although the constant rains are making for slow progress. The City of Warrensburg has written a resolution that includes Blind Boone Park in the city park's system upon completion.

Ordinance No. 920

|

| An ordinance naming and designating the West Pine Street Park "Willie 'Blind' Boone Park" Be it ordained by the council of the City of Warrensburg, Missouri, As Follows: Section 1. That the Negro Park located on West Pine Street in the City of Warrensburg, Missouri be and the same is hereby named Willie "Blind" Boone Park. Section 2. That this ordinance shall be in full force and effect from and after its passage by the council and approval by the Mayor. Passed by the council this 18 day of March, 1954 Approved by the Mayor this 23rd day of March, 1954 |

Contact Information:

"Blind" Boone Park Renovation Group

131 S.W. 300

Warrensburg, MO. 64093

Phone (660)441-0879

Email info@blindboonepark.org

John William "Blind" Boone

John William “Blind” Boone, the son of a former slave, overcame blindness, poverty and discrimination to become an amazing composer and concert pianist. His philosophy “Merit, Not Sympathy, Wins” is as valuable a lesson today as it was in his time.

Boone is credited, along with Louis Moreau Gottschalk, with giving legitimacy to black music. Scott Joplin, “Blind” Boone and James Scott are considered Missouri’s “Big Three”. Missouri is considered the hub of ragtime, the precursor to jazz and the first completely American music. He was known to play some ragtime, Boone’s first love though was classical music, particularly that of German composer Franz Liszt.

Boone was a committed philanthropist who supported local causes and opened his home to the community. He donated generously to several churches, and gave his time and talents to local youth. He died in 1927, his wife Eugenia in 1931. There Columbia Cemetery gravesites were unmarked until 1971.

It’s time to restore the lost legacy of “Blind” Boone. The exterior renovations of his home are largely complete, and have remained true to the original era of the structure. But the interior and grounds await their own refurbishing.

|

| John William Boone Death Certificate October 4, 1927 |

Born on December 11, 1941 in Kansas City, Missouri, Frank Townsell grew up in Kansas City and began his piano studies at age of five. In 1959 Frank made his first appearance as a piano soloist with the Kansas City Philharmonic Guild Orchestra.

Frank received a Bachelor or Arts in French Literature from the University of Missouri while studying piano with Richard Canterbury and a Master of Music degree in Piano Performance from the University of British Columbia while studying with Dale Reubart.

In 1971, he received a Diploma from the American Conservatory in Fontainbleau, France. His teachers were Nadia Boulanger, Robert Casadesus and Jean-Jacques Painchaud. He then studied privately with Nadia Boulanger until his return to the United States in 1972.

Frank scored a triumph at his Paris debut, receiving an ovation which led to further successful appearances in France. At Reid Hall in Paris he was a soloist on a recital program in honor of the legendary Mlle. Boulanger and was also featured in recitals at the Fontainbleau Palace where he played for Queen Frederika of Greece.

Mlle. Boulanger said of Mr. Townsell's talent:

"This is a musician of real value and complete seriousness. I recommend him highly."

Frank has appeared in music festivals in Columbia, Missouri and in London, England.

| |

| September 3, 1903 Newspaper, Blind Boone's home burns down, Warrensburg, Missouri |

Date:

Tue, 1864-05-17

John William “Blind” Boone was born on this date in 1864. He was an African American musician.

Born at a federal army camp near Miami, Missouri, his mother, Rachel, was a runaway slave who had taken refuge with the regiment of the Union Army as a cook. The descendants of pioneer Daniel Boone owned her. The regiment's bugler fathered the child, but they were never to know each other. Shortly after Boone was born, his mother moved to Warrensburg, Missouri where she earned a living by cleaning the homes of prominent families. At six months of age, the Young Boone became very ill with "brain fever."

Only a very radical surgical procedure offered a chance to save the child's life releasing pressure from the swelling of the brain. There was one way to accomplish that, by surgical removal of the eyes. The operation was performed. John William lost his sight, but not his very extensive intelligence. Greatly loved, John William was a happy, musically gifted child. At age three, he was capable of beating out rhythms. He had a tin whistle at age five with which he could play tunes and imitate sounds in nature like birds. Soon John organized a band with instruments that included tin whistle, drum, and tambourine. Rachel sought ways to have John educated and succeeded in recruiting the town's assistance.

Warrensburg's city fathers purchased the railroad ticket that brought John William to the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis for two and one-half years. He quickly demonstrated his ability to reproduce on the piano any musical piece he heard. Despite his musical giftedness, the school was teaching him to make brooms. Driven to find outlets for his interests and talents, Boone would sneak out to the 'adult' area of town to hear the Ragtime piano. School officials finally expelled him from school but a conductor befriended and allowed him to ride the train home in exchange for entertaining passengers by playing his harmonica. In Warrensburg, Boone lived in the Black community for the first time in his life. Rachel had married widower Harrison Hendrix, the father of five, when John was eight years old. Wanderlust gripped him, however, and he strayed from home repeatedly at times, with regrettable consequences. The Christmas holidays of 1879 were to bring dramatic positive change to Boone’s life.

The gifted young musician was invited to participate in a festival at the Second Baptist Church in Columbia. The event was an annual gift to the community by a very successful builder and contractor, John Lange, Jr. Boone was invited back for a concert in March, 1880 one in which he was featured with a second sightless black pianist, Tom Bethune known as 'Blind Tom'. John William Boone's professional career was launched with the event and John Lange, Jr. took on the role of his manager.

Lange began by sending John William to Christian College in Columbia to further his musicianship introducing him to the European classical composers. Further, Lange's organizational skills were outstanding. To transcend the stigma of disability, Lange adapted the motto, "Merit, not sympathy, wins" for the J. W. Boone Music Co. To make significant Boone’s capacity to reproduce anything he heard, Lange made it known that one thousand dollars would be given to anyone who could stump him by playing something the artist could not play back accurately.

Boone and Lange never had to make good on the offer. Lang also hired advance men, who would travel to towns to advertise Boone's abilities and make the necessary arrangements prior to the arrival of the great man. His career peaked between 1885 and 1916, earning between $150 and $600 on their best nights. His company trained many young singers and music agents. By 1916, Boone toured US, Canada, and Mexico and (reportedly) England, Scotland and Wales but no documentation has yet been found for the overseas events.

Lange wrote about the period from 1880 to 1915 where they would travel 10 months each year, with 6 concerts per week, a total of 8, 650 concerts. Distance traveled averaged 20 miles per day or 216,000 miles and they slept in 8,250 beds. Boone played mainly in churches and concert halls and to segregated audiences. After he became popular, piano companies provided the pianos so he did not have to haul them by horse and wagon. He wore out 16 pianos by 1915. Boone married Lange's youngest sister in 1889 and never recovered from Lange's death in 1916.

He moved into a permanent home in Columbia Missouri, which is now on the national register. Besides a classical repertoire, Boone played plantation melodies, religious songs and Ragtime. He sang minstrel tunes/plantation songs, wrote and sang 'coon' songs as all Black performers did that came out of the minstrel stereotypes of earlier years. Religious songs included "Nearer My God to Thee" and others. In 1912, he was contacted by the QRS Piano Roll Company and became one of the first black artists to cut piano rolls. Boone gave generously to black churches and schools, and at one time he had had an income of $17,000 per year. Boone gave many benefit concerts to further Black schools and churches in the Columbia area. He was just 5 feet tall but was a very impressive figure. Because he could not walk without guidance, he frequently carried a child upon his shoulders as a navigator. He had an astounding memory and was called a walking encyclopedia.

Boone could tell a child's age by putting his hand upon a child's head. H e had a very happy and warm personality and children loved him. Boone also belonged to fraternal organizations, yet his only family was his wife and his mother Rachel who died in 1901. After 1920, competition from movies and radio made it very difficult to secure bookings. Boone did a final big tour in the East in 1919 and 1920. His last concert was on May 31, 1927. He died of a heart attack on October 4, 1927. The funeral was a major event in the black community in Columbia, Missouri.

Reference:

The African American Atlas

Black History & Culture an Illustrated Reference

by Molefi K. Asanta and Mark T. Mattson

Macmillam USA, Simon & Schuster, New York

ISBN 0-02-864984-2

Music of Blind Boone

Boone’s style of classical and ragtime/early jazz was groundbreaking. Among his many compositions, the “Marshfield Tornado,” which musically told the story of a deadly tornado that hit Marshfield, Missouri, was perhaps the best known.

Below are links to Boone’s music. Experience his talent for yourself.

Sparks Galop De Concert

Sparks: Galop de Concert

Southern Rag Medley No.2 – Strains From Flat Branch

Medley #2: Strains From Flat Branch

Warrensburg and Columbia, Missouri

On May 17, 1864, as the Civil War entered its final year, John William Boone was born in Miami, Saline County, Missouri. His mother, Rachel Boone, worked as a cook in the federal military camp of the Seventh Militia. She later told her son, whom she called Willy, that his father was a bugler in the army. Born into slavery, Rachel had either escaped or was freed by federal soldiers.

Rachel Boone Hendricks

Rachel moved to Warrensburg with her infant son to work as a servant for various families. Around the age of six months, the baby developed cerebral meningitis or “brain fever.” The illness was often fatal, and the only treatment known at the time led to blindness. Doctors today would treat the illness with antibiotics.

Warrensburg, circa 1867

As Willy grew, the townspeople noticed his talent for music. They encouraged him with gifts of simple instruments, such as a tin whistle, a French harp (or harmonica), and a triangle. Willy started a band with his friends. They played for parades and special gatherings to earn money.

When Willy was about eight years old, his mother married Harrison Hendricks. Rachel and Willy moved into a one-room cabinwith her new husband and his five children.

Boone’s style of classical and ragtime/early jazz was groundbreaking. Among his many compositions, the “Marshfield Tornado,” which musically told the story of a deadly tornado that hit Marshfield, Missouri, was perhaps the best known.

Below are links to Boone’s music. Experience his talent for yourself.

Sparks Galop De Concert

Sparks: Galop de Concert

Southern Rag Medley No.2 – Strains From Flat Branch

Medley #2: Strains From Flat Branch

Warrensburg and Columbia, Missouri

On May 17, 1864, as the Civil War entered its final year, John William Boone was born in Miami, Saline County, Missouri. His mother, Rachel Boone, worked as a cook in the federal military camp of the Seventh Militia. She later told her son, whom she called Willy, that his father was a bugler in the army. Born into slavery, Rachel had either escaped or was freed by federal soldiers.

Rachel Boone Hendricks

Rachel moved to Warrensburg with her infant son to work as a servant for various families. Around the age of six months, the baby developed cerebral meningitis or “brain fever.” The illness was often fatal, and the only treatment known at the time led to blindness. Doctors today would treat the illness with antibiotics.

Warrensburg, circa 1867

As Willy grew, the townspeople noticed his talent for music. They encouraged him with gifts of simple instruments, such as a tin whistle, a French harp (or harmonica), and a triangle. Willy started a band with his friends. They played for parades and special gatherings to earn money.

When Willy was about eight years old, his mother married Harrison Hendricks. Rachel and Willy moved into a one-room cabinwith her new husband and his five children.

Education

With his disability Willy needed a special school. Several Warrensburg residents helped Rachel send her son to the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis. Former Missouri senator Francis Cockrell persuaded Johnson County officials to pay for the train ride to St. Louis and tuition at the school.

With his disability Willy needed a special school. Several Warrensburg residents helped Rachel send her son to the Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis. Former Missouri senator Francis Cockrell persuaded Johnson County officials to pay for the train ride to St. Louis and tuition at the school.

A group of ladies helped sew the clothing Willy would need. In the fall of 1872, nine-year-old Willy traveled alone 225 miles to St. Louis.

Boone's name in the enrollment ledger

Boone quickly learned to love the school. The program taught students skills to help them gain their independence and also emphasized music. The teachers tried to get Boone to study Braille and to learn the broom trade so he could support himself, but he was not interested in reading or making brooms. He would often steal away from his studies to listen to the advanced students as they practiced piano.

Enoch Donnelly, an older white student, appreciated the young boy’s curiosity and often invited Boone to hear him play. After he heard Boone mimicking one of his classical music pieces on the piano, Donnelly gave up a portion of his own practice time to teach the eager student. Boone could remember and play everything he heard, even if he had only heard it once.

Soon the young prodigy was entertaining gatherings at the home of the school superintendent. At home in Warrensburg during school breaks, Boone played piano for church services and social gatherings to earn money to help his family.

The darker sideof St. Louis

Once, upon his return from a school break, he found a new superintendent who did not believe black students should have the same privileges as whites. He would not allow black students to play piano. Unable to bear the new rules, Boone started skipping class to go to the “Tenderloin District” near the school. In the district, a poor and densely populated area, he listened to and played music with the African American musicians who worked in the saloons. The principal eventually dismissed Boone from the school because of his absences.

Ashamed to return to Warrensburg and face his mother, the young boy tried to make a living with his music in St. Louis. Eventually, broke and hungry, Boone returned home through the kindness of A. J. Kerry, a white railroad conductor. Kerry befriended the homeless boy and arranged for Boone to travel home on the train.

Boone organized a band

Back in Warrensburg, Boone earned money playing piano for the Foster School, a white school, and again formed a band of street musicians. After hearing Boone play his harmonica, a local gambler named Mark Cromwell convinced the young boy he could supply him with concert engagements. Lured away from his mother by Cromwell’s tales and flattery, the young boy soon realized he would see none of the promised money.

Boone's life story

Boone played his harmonica on the streets of many Missouri towns just as he had done in Warrensburg, but now Cromwell kept the money. At one point, the gambler lost Boone in a card game. The winner kept the boy in a locked room until Cromwell managed to “steal” him back three days later. Boone’s stepfather searched for the boy and finally brought him home. Throughout his life, some people tried to take advantage of the good–natured Boone.

Boone's name in the enrollment ledger

Boone quickly learned to love the school. The program taught students skills to help them gain their independence and also emphasized music. The teachers tried to get Boone to study Braille and to learn the broom trade so he could support himself, but he was not interested in reading or making brooms. He would often steal away from his studies to listen to the advanced students as they practiced piano.

Enoch Donnelly, an older white student, appreciated the young boy’s curiosity and often invited Boone to hear him play. After he heard Boone mimicking one of his classical music pieces on the piano, Donnelly gave up a portion of his own practice time to teach the eager student. Boone could remember and play everything he heard, even if he had only heard it once.

Soon the young prodigy was entertaining gatherings at the home of the school superintendent. At home in Warrensburg during school breaks, Boone played piano for church services and social gatherings to earn money to help his family.

The darker sideof St. Louis

Once, upon his return from a school break, he found a new superintendent who did not believe black students should have the same privileges as whites. He would not allow black students to play piano. Unable to bear the new rules, Boone started skipping class to go to the “Tenderloin District” near the school. In the district, a poor and densely populated area, he listened to and played music with the African American musicians who worked in the saloons. The principal eventually dismissed Boone from the school because of his absences.

Ashamed to return to Warrensburg and face his mother, the young boy tried to make a living with his music in St. Louis. Eventually, broke and hungry, Boone returned home through the kindness of A. J. Kerry, a white railroad conductor. Kerry befriended the homeless boy and arranged for Boone to travel home on the train.

Boone organized a band

Back in Warrensburg, Boone earned money playing piano for the Foster School, a white school, and again formed a band of street musicians. After hearing Boone play his harmonica, a local gambler named Mark Cromwell convinced the young boy he could supply him with concert engagements. Lured away from his mother by Cromwell’s tales and flattery, the young boy soon realized he would see none of the promised money.

Boone's life story

Boone played his harmonica on the streets of many Missouri towns just as he had done in Warrensburg, but now Cromwell kept the money. At one point, the gambler lost Boone in a card game. The winner kept the boy in a locked room until Cromwell managed to “steal” him back three days later. Boone’s stepfather searched for the boy and finally brought him home. Throughout his life, some people tried to take advantage of the good–natured Boone.

Turning Point

John Lange Jr.

Boone met John Lange Jr. in December 1879. A contractor by trade, Lange owned an entertainment hall in Columbia and hired Boone to play the Christmas program there. He recognized Boone’s talent and also the young boy’s vulnerability.

Lange wrote to Rachel Boone Hendricks to ask if he could take over the musician’s career. He promised to handle Boone’s training and care. The boy’s mother would receive part of his earnings every month until Boone turned twenty-one. When he turned twenty-one, Boone would become a partner in the Blind Boone Company. Lange kept his word. Boone played one of his first concerts as part of the Boone Company in January 1880. The ticket sales totaled a disappointing $7.00.

Blind Tom Wiggins

Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins came to play a concert in Columbia in March 1880. Like Boone, Tom could play any music he heard. As part of the program, his manager challenged anyone in the audience to repeat Tom’s tunes. Tom would play back any tune others played for him. Unlike many others before him, Boone was able to repeat Tom’s music note-for-note.

Early Struggles

Blind Boone at age 15

The first few years Boone traveled with Lange, he was billed under the name “Blind John.” In addition to the fifteen-year-old Boone, a ten-year-old soprano named Stella May accompanied them. Lange often had to bring a good piano along in a wagon or by train because the churches and halls in the small towns where they played did not own one.

Marshfield tornado, April 18, 1880

Just before Boone was scheduled to play in Marshfield, Missouri, a tornado hit the small town on April 18, 1880. The twister killed almost 100 people and injured twice as many. Few buildings other than the courthouse remained standing. Lange read Boone the newspaper articles reporting the tragedy. The musician was inspired to compose “The Marshfield Tornado,” which included effects that sounded like the tornado. After some discussion, Lange and Boone decided to continue on to the scheduled performance in Marshfield.

Many survivors of the tragedy came to hear Boone play. His first piece was the new cyclone composition. Much to the performer’s dismay, the true-to-life sounds of his music caused some to panic and flee the building, thinking another tornado was coming. Despite their own financial hardships, Boone and Lange donated the proceeds from the concert to help rebuild the town. “Marshfield Tornado” became a regular part of Boone’s program, but he always played it last in case it frightened his audience away.

Concerts announced by Ed the parrot

Without the advantage of modern radio or television, word of Boone’s talent spread slowly. As the Boone Company struggled in its early years, Lange sometimes feared he would have to get a job digging coal to keep the company going. When funds ran low, Lange sent the other musicians home, and the two partners traveled the country alone. They were often broke and suffered many difficulties, such as hotel and music store fires and train wrecks. At one point, a business partner ran off with the company piano.

Promotional leaflet

Although many of his friends believed he was foolish to give up his business to promote a little-known black musician, Lange never regretted it. “I have lost all I had more than once, trying to make Boone a success, but I am proud today that I have stuck with it.”

Merit, Not Sympathy, Wins

Mary R. Sampson

Blind Boone played piano by ear. Since he could not read music, he learned new songs by listening closely to other musicians. Around 1883 he took lessons from Mary R. Sampson in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Sampson helped Boone acquire better piano technique and taught him new classical music pieces. After his work with Sampson, Boone’s career began to take off. It was around this time that the group began billing themselves as the Blind Boone Touring Company.

Lange wanted everyone to understand that Boone was a person of talent and achievement, not just a figure of curiosity and sympathy like Blind Tom. He developed the motto “Merit, Not Sympathy, Wins,” which was often printed on the concert program.

Boone played classical music to please one section of his audience and to demonstrate his skill. Then he would play popular music, folk tunes, and Negro spirituals to please another. He called this approach “putting the cookies on the lower shelf” so everyone could enjoy them. Like Blind Tom, Boone challenged his audience to play music for him to imitate.

Haden Opera House Advertisement

Through a carefully constructed program of music, Blind Boone exposed his audiences, both black and white, to the power of music. He developed a uniquely American sound by combining his classical training with his understanding of popular music. Boone was the first performer to unite these musical forms on the concert stage. Many believe his adoption of the “ragged” or syncopated rhythms of the African American community and the heavy bass line of his informal musical compositions inspired the development of ragtime music.

Success at Last

Boone on tour

With Boone’s new approach to his program, success came quickly. Black and white audiences alike came to hear Boone play and enjoyed his music. Prejudices still remained, however. In 1896 the United States Supreme Court upheld segregation laws as long as facilities and opportunities for both races were viewed as equal. In the concert halls, churches, courthouses, and tents where the Boone Company played, the white audiences and black audiences usually sat apart or attended separate programs. Often the black audience was restricted to the worst seats. Some white hotels refused to give the company members lodging, and there were often no black-owned hotels in towns. Many times black families offered the company their hospitality and put them up in their homes.

Boone at Clarksburg depot

Blind Boone became one of the first black artists recorded by the QRS piano roll company in 1912. He played eleven selections while a machine punched the notes on the roll. Boone’s ability to play many notes rapidly made it difficult to record him accurately. His best-known composition, “The Marshfield Tornado,” was never recorded or written down because it was too complex.

Home Life

Eugenia and John William Boone

In 1889 Boone married Eugenia Lange, John Lange’s youngest sister. She traveled with the company for many years as treasurer and often read to her husband. Boone was especially interested in the geography of the country. With his excellent memory, he recalled all the railroad routes he had taken when young and the many places he had traveled.

The young couple purchased a home at 10 North Fourth Street in Columbia. With Boone’s growing financial success, he was able to buy several pianos. Boone could play almost any instrument, but the piano remained his favorite. Often in the summer, when he was not on tour, he spent six hours a day practicing new music. Boone believed the only way to achieve greatness was through study and practice.

John Lange Jr.

Boone met John Lange Jr. in December 1879. A contractor by trade, Lange owned an entertainment hall in Columbia and hired Boone to play the Christmas program there. He recognized Boone’s talent and also the young boy’s vulnerability.

Lange wrote to Rachel Boone Hendricks to ask if he could take over the musician’s career. He promised to handle Boone’s training and care. The boy’s mother would receive part of his earnings every month until Boone turned twenty-one. When he turned twenty-one, Boone would become a partner in the Blind Boone Company. Lange kept his word. Boone played one of his first concerts as part of the Boone Company in January 1880. The ticket sales totaled a disappointing $7.00.

Blind Tom Wiggins

Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins came to play a concert in Columbia in March 1880. Like Boone, Tom could play any music he heard. As part of the program, his manager challenged anyone in the audience to repeat Tom’s tunes. Tom would play back any tune others played for him. Unlike many others before him, Boone was able to repeat Tom’s music note-for-note.

Early Struggles

Blind Boone at age 15

The first few years Boone traveled with Lange, he was billed under the name “Blind John.” In addition to the fifteen-year-old Boone, a ten-year-old soprano named Stella May accompanied them. Lange often had to bring a good piano along in a wagon or by train because the churches and halls in the small towns where they played did not own one.

Marshfield tornado, April 18, 1880

Just before Boone was scheduled to play in Marshfield, Missouri, a tornado hit the small town on April 18, 1880. The twister killed almost 100 people and injured twice as many. Few buildings other than the courthouse remained standing. Lange read Boone the newspaper articles reporting the tragedy. The musician was inspired to compose “The Marshfield Tornado,” which included effects that sounded like the tornado. After some discussion, Lange and Boone decided to continue on to the scheduled performance in Marshfield.

Many survivors of the tragedy came to hear Boone play. His first piece was the new cyclone composition. Much to the performer’s dismay, the true-to-life sounds of his music caused some to panic and flee the building, thinking another tornado was coming. Despite their own financial hardships, Boone and Lange donated the proceeds from the concert to help rebuild the town. “Marshfield Tornado” became a regular part of Boone’s program, but he always played it last in case it frightened his audience away.

Concerts announced by Ed the parrot

Without the advantage of modern radio or television, word of Boone’s talent spread slowly. As the Boone Company struggled in its early years, Lange sometimes feared he would have to get a job digging coal to keep the company going. When funds ran low, Lange sent the other musicians home, and the two partners traveled the country alone. They were often broke and suffered many difficulties, such as hotel and music store fires and train wrecks. At one point, a business partner ran off with the company piano.

Promotional leaflet

Although many of his friends believed he was foolish to give up his business to promote a little-known black musician, Lange never regretted it. “I have lost all I had more than once, trying to make Boone a success, but I am proud today that I have stuck with it.”

Merit, Not Sympathy, Wins

Mary R. Sampson

Blind Boone played piano by ear. Since he could not read music, he learned new songs by listening closely to other musicians. Around 1883 he took lessons from Mary R. Sampson in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Sampson helped Boone acquire better piano technique and taught him new classical music pieces. After his work with Sampson, Boone’s career began to take off. It was around this time that the group began billing themselves as the Blind Boone Touring Company.

Lange wanted everyone to understand that Boone was a person of talent and achievement, not just a figure of curiosity and sympathy like Blind Tom. He developed the motto “Merit, Not Sympathy, Wins,” which was often printed on the concert program.

Boone played classical music to please one section of his audience and to demonstrate his skill. Then he would play popular music, folk tunes, and Negro spirituals to please another. He called this approach “putting the cookies on the lower shelf” so everyone could enjoy them. Like Blind Tom, Boone challenged his audience to play music for him to imitate.

Haden Opera House Advertisement

Through a carefully constructed program of music, Blind Boone exposed his audiences, both black and white, to the power of music. He developed a uniquely American sound by combining his classical training with his understanding of popular music. Boone was the first performer to unite these musical forms on the concert stage. Many believe his adoption of the “ragged” or syncopated rhythms of the African American community and the heavy bass line of his informal musical compositions inspired the development of ragtime music.

Success at Last

Boone on tour

With Boone’s new approach to his program, success came quickly. Black and white audiences alike came to hear Boone play and enjoyed his music. Prejudices still remained, however. In 1896 the United States Supreme Court upheld segregation laws as long as facilities and opportunities for both races were viewed as equal. In the concert halls, churches, courthouses, and tents where the Boone Company played, the white audiences and black audiences usually sat apart or attended separate programs. Often the black audience was restricted to the worst seats. Some white hotels refused to give the company members lodging, and there were often no black-owned hotels in towns. Many times black families offered the company their hospitality and put them up in their homes.

Boone at Clarksburg depot

Blind Boone became one of the first black artists recorded by the QRS piano roll company in 1912. He played eleven selections while a machine punched the notes on the roll. Boone’s ability to play many notes rapidly made it difficult to record him accurately. His best-known composition, “The Marshfield Tornado,” was never recorded or written down because it was too complex.

Home Life

Eugenia and John William Boone

In 1889 Boone married Eugenia Lange, John Lange’s youngest sister. She traveled with the company for many years as treasurer and often read to her husband. Boone was especially interested in the geography of the country. With his excellent memory, he recalled all the railroad routes he had taken when young and the many places he had traveled.

The young couple purchased a home at 10 North Fourth Street in Columbia. With Boone’s growing financial success, he was able to buy several pianos. Boone could play almost any instrument, but the piano remained his favorite. Often in the summer, when he was not on tour, he spent six hours a day practicing new music. Boone believed the only way to achieve greatness was through study and practice.

Boone's Other Talents and Traits

John Lange and Boone

Once Boone met someone—child or adult—he always recognized the voice and remembered the name, even many years later. He also talked about his ability to “see” colors, often identifying the color of fabric or the hair on a child’s head through touch. Boone could describe the appearance of a person after hearing the sound of his voice. He called his ability “seeing with my mind.”

Like his partner John Lange, Boone was generous to those around him. He supported churches and other organizations through donations and loans. He provided loans to Christian College (now Columbia College) and the First Christian Church of Columbia. In gratitude, the church accepted Boone as their first black member.

Once in Kansas, the members of the Boone Company were denied rooms at the only local hotel. An elderly relative offered them the use of her home. When Boone learned she had approximately $360 remaining on her mortgage, a large amount in those days, he paid off her loan. Lange often said, “Boone is charitable and I have been authorized by him whenever I see a deserving person in need of assistance to assist such person in his name.”

Despite many hardships, Boone never appeared down or sorry for himself. Toward the end of his life, he said, “Blindness has not affected my disposition. It has never made me at outs with the world. Many times I regard it as a blessing, for had I not been blind, I would not have given the inspiration to the world that I have. I have shown that no matter how a person is afflicted, there is something that he can do worthwhile.”

The End

John Lange and Boone

Once Boone met someone—child or adult—he always recognized the voice and remembered the name, even many years later. He also talked about his ability to “see” colors, often identifying the color of fabric or the hair on a child’s head through touch. Boone could describe the appearance of a person after hearing the sound of his voice. He called his ability “seeing with my mind.”

Like his partner John Lange, Boone was generous to those around him. He supported churches and other organizations through donations and loans. He provided loans to Christian College (now Columbia College) and the First Christian Church of Columbia. In gratitude, the church accepted Boone as their first black member.

Once in Kansas, the members of the Boone Company were denied rooms at the only local hotel. An elderly relative offered them the use of her home. When Boone learned she had approximately $360 remaining on her mortgage, a large amount in those days, he paid off her loan. Lange often said, “Boone is charitable and I have been authorized by him whenever I see a deserving person in need of assistance to assist such person in his name.”

Despite many hardships, Boone never appeared down or sorry for himself. Toward the end of his life, he said, “Blindness has not affected my disposition. It has never made me at outs with the world. Many times I regard it as a blessing, for had I not been blind, I would not have given the inspiration to the world that I have. I have shown that no matter how a person is afflicted, there is something that he can do worthwhile.”

The End

Blind Boone

After seeing his protégé achieve success, John Lange died in 1916 at the age of seventy-six. Boone hired several managers in succession to take Lange’s place, but never found a replacement for his longtime friend. He continued to tour and practice with the same rigorous schedule. In January 1926 Boone played two live performances at the KFRU radio station in Columbia, Missouri. The Columbia Tribune reported that the programs were the most popular ever heard on the station.

Obituary from

Columbia Tribune