The Second Annual Re-Union.

CIVIL AT WAR VETERANS WILL HAVE A GREAT TIME PERTLE SPRINGS, NEAR WARRENSBURG, MISSOURI, DURING THE EARLY FALL. (Camp Frederick Douglas)

July 4, 1908 Sedalia Weekly Conservator

Rev. James W. Jackson, Colonel, of Clinton, Missouri, Gives An Explanatory Outline of The Movement.

The first annual reunion was held at the Pertle Springs, near Warrensburg Missouri, in October 1907. It proved to be a most fortunate move both for the old soldiers and the citizens. It would be impossible to convey too many minds or easily describe the happy effect which this first annual reunion threw once a heart which otherwise might have been sad, cold, and selfish. And it did arouse both the old soldier and the citizen to the highest pitch of enthusiasm. The officers and the executive committee elected at the first annual reunion will appear on the Circular Letters, together with the facilities of transportation and accommodations. The second Annual Reunion will meet at Pertle Springs near Warrensburg Missouri, in the fall of 1908, the date of which will appear on the on the program.

|

| 22th Regiment U. S. Colored Troops |

|

| Sgt Major Christian Fleetwood - American Civil War Medal of Honor recipient |

|

| US Colored Troops Medal |

Comrades: The men of each generation, in such a family as the Negro soldiers of the Civil War, have some great Mission, ours is to transmit the experiences and the observations in the instructions in the discipline, in the drill, on the dress parade, around the camp-fire, on the march and on the battle-field of glory, to the present generations, thru the medium of the annual reunion. Only those acquainted with these can appreciate the full meaning of the annual reunion. For these are not written in the histories of the Civil War, was in any other hooks; but they are written only in the heart, soul, and mind of the old soldiers hence the necessity of perpetuating the annual reunion on the part of the old soldiers, and hence, the necessity of attending the annual reunion on this part of present generations. The annual reunion is a patent factor in tolling the number of agencies that work in bringing about a chosen sympathy and cooperation between the Veteran and the Citizen. Its effect upon the general struggle of civilization and industry, lies in this encouragement and moral weight that it gives to the Negro race in various occupations of life. For example, during the first annual reunion as stated above, quite a number of prominent Negro citizens of Johnson County (Missouri) were in attendance, and they were so favorably impress with the annual reunion, that they concluded to return home and organize a permanent Annual Fair Association exhibit the products of Johnson County. They ask veterans permission to hold their first annual fair in connection with the Second Annual Reunions, winch was reunion that never takes a step backward in the scale of civilization and industry. Done by order of the Rev. RICHARD RUSH, Commander in Chief of the Negro Soldiers of the Civil War of the State of Missouri.

The word reunion thrills the old veteran’s nerves like an electric shock. The events of the Civil War came back to him with an extraordinary vividness of expression. The annual reunion is in itself, an appeal to an old time honored alliance between comrades, sanctified by common sufferings and endeared by mutual associations shared in the duties and incidents of Military life. The annual reunion is most firmly embedded in the old veteran's memory. Indeed, it has always for him a significance quite independence of its obvious import. It symbolizes the duties, obligations the accidents, the experiences, the observations, and the tender memories of which all his Military life has taught him. The annual reunion of the Negro soldiers of the Civil War of the state of Missouri, is truly an annual reunion, an annual reunion where people of all' creeds and opinions can meet together, and are actually treated alike. The spirit of the Republic reigns at this annual reunion rather Racial Distinction or Social Status. There is neither Black, Yellow, White, Red, nor Brown, but all are American citizens, and all are welcome. Among those who have help to preserve the Union, few have stamped themselves the more clearly upon the nation's memory than the Negro soldiers of the Civil War. He ever remains a singular vivid image before the nations' eyes. Indeed, the obligation under which the Negro soldier of the Civil War has laid the Negro race and the debt all the nation owes to one who has help to preserve the Union, should inspire the Negro race, and the nation, with a liberal enthusiasm for the annual reunion, and a zeal for perpetuating the experiences, the observations and the tender memories of the old soldiers Military life. The annual reunion of the Negro veteran of Civil War, with its national character, its national reputation, its national honors, its national rights and its national privileges, is of sufficient weight to have the right influence in the formation of the Negro's life. It furnishes great opportunities to the Negro race. The Negro race robs itself of those opportunities when it neglects to attend the annual reunion. The Negro veteran of the Civil War may be assured that nowhere could his time, talent and attention find a better object for their employment, than the annual reunion. He needs no other incentive to perpetuate the annual reunion man in prospect before him of furthering the happiness and welfare of the Negro race, comrades, let us rally to me annual reunion with an enthusiasm equal to its importance, annual reunion in reality and not merely in name, an annual.

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments in the United States Army composed of African-American(colored) soldiers; they were first recruited during the American Civil War, and by the end of that war in April, 1865, the 175 USCT regiments constituted about one-tenth the manpower of the Union Army. In the decades that followed the USCT soldiers fought in the Indian Wars in the American West, where they became known as the Buffalo Soldiers; they received the nickname from Native Americans who compared their hair to the fur of bison.

History

Confiscation Act

The U.S. Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act in July 1862. It freed slaves whose owners were in rebellion against the United States, and a militia act empowered the President to use freed slaves in any capacity in the army. President Abraham Lincoln was concerned with public opinion in the four border states that remained in the Union, as they had numerous slaveholders, as well as with northern Democrats who supported the war but were less supportive of abolition than many northern Republicans. Lincoln opposed early efforts to recruit black soldiers, although he accepted the Army's using them as paid workers.

Union Army setbacks in battles over the summer of 1862 led Lincoln to emancipate all slaves in states at war with the Union. In September 1862, Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, announcing that all slaves in rebellious states would be free as of January 1. Recruitment of colored regiments began in full force following the Proclamation of January 1863.

|

| 1st Sgt. Octavius McFarland, Sixty-second U.S. Colored Infantry |

The United States War Department issued General Order Number 143 on May 22, 1863, establishing the Bureau of Colored Troops to facilitate the recruitment of African-American soldiers to fight for the Union Army.[3] Regiments, including infantry, cavalry, engineers, light artillery, and heavy artillery units, were recruited from all states of the Union and became known as the United States Colored Troops (USCT).

|

| Pvt. Abram Garvin, 108th U.S. Colored Infantry |

Approximately 175 regiments composed of more than 178,000 free blacks and freedmen served during the last two years of the war. Their service bolstered the Union war effort at a critical time. By war's end, the men of the USCT composed nearly one tenth of all Union troops. The USCT suffered 2,751 combat casualties during the war, and 68,178 losses from all causes. Disease caused the most fatalities for all troops, black and white.

USCT regiments were led by white officers, and rank advancement was limited for black soldiers. The Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments in Philadelphia opened the Free Military Academy for Applicants for the Command of Colored Troops at the end of 1863. For a time, black soldiers received less pay than their white counterparts, but they (and their supporters) lobbied and gained equal pay. Notable members of USCT regiments included Martin Robinson Delany, and the sons of Frederick Douglass.

The courage displayed by colored troops during the Civil War played an important role in African Americans gaining new rights. As the abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote:

"Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship."

The historian Steven Hahn proposes that when slaves organized themselves and worked with the Union Army during theAmerican Civil War, including as some regiments of the USCT, their actions comprised a slave rebellion that dwarfed all others.

Volunteer regiments

Before the USCT was formed, several volunteer regiments were raised from free black men, including freedmen in the South. In 1863 the former slave William Henry Singleton helped recruit 1,000 blacks from escaped slaves in New Bern, North Carolina for the First North Carolina Colored Volunteers. He became a sergeant in the 35th USCT. Freedmen from the Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony, established in 1863 on the island, also formed part of the FNCCV and the 35th. Nearly all of the volunteer regiments were converted into USCT units.

In 1922 Singleton published his memoir, a slave narrative, of his journey in going from slavery to freedom and being a Union soldier. Glad to participate in reunions, years later at the age of 95, he marched in a Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) event in 1938.

State volunteers

Four regiments were considered Regular units, rather than auxiliaries. Their veteran status allowed them to get valuable federal government jobs after the war, from which African Americans had usually been excluded in earlier years. But, the men received no formal recognition for combat honors and awards until the turn of the 20th century. The units were:

- 5th Massachusetts (Colored) Volunteer Cavalry Regiment

- 54th Massachusetts (Colored) Volunteer Infantry Regiment

- 55th Massachusetts (Colored) Volunteer Infantry Regiment

- 29th Connecticut (Colored) Volunteer Infantry Regiment

Corps d'Afrique

The Corps d'Afrique, one of many Louisiana Union Civil War units, was formed in New Orleans after the city was taken and occupied by Union forces. It was formed in part from the Louisiana Native Guards. The Native Guards were former militia units raised in New Orleans. They were property-owning free people of color (gens du couleur libres).

Free mixed-race people had developed as a third class in New Orleans since the colonial years. Although the men had wanted to prove their bravery and loyalty to the Confederacy like other Southern property owners, the Confederates did not allow these men to serve and confiscated their arms. The Confederates said that enlisting black soldiers would hurt agriculture. Since the units were composed of freeborn creoles and black freemen, it was clear that the underlying objection was to having black men serve at all.

For later units of the Corps d'Afrique, the Union recruited freedmen from the refugee camps. Liberated from nearby plantations, they and their families had no means to earn a living and no place to go. Local commanders, starved for replacements, started equipping volunteer units with cast-off uniforms and obsolete or captured firearms. The men were treated and paid as auxiliaries, performing guard or picket duties to free up white soldiers for maneuver units. In exchange their families were fed, clothed and housed for free at the Army camps; often schools were set up for them and their children.

Despite class differences between freeborn and freedmen the troops of the Corps d'Afrique served with distinction, including at the Battle of Port Hudson and throughout the South. Its units included:

- 4 Regiments of Louisiana Native Guards (renamed the 1st-4th Corps d'Afrique Infantry, later made into the 73rd-76th US Colored Infantry on April 4, 1864).

- 1st and 2nd Brigade Marching Bands, Corps d'Afrique (later made into Nos. 1 and 2 Bands, USCT).

- 1 Regiment of Cavalry (1st Corps d'Afrique Cavalry, later made into the 4th US Colored Cavalry).

- 22 Regiments of Infantry (1st-20th, 22nd, and 26th Corps d'Afrique Infantry, later converted into the 77th-79th, 80th-83rd, 84th-88th, and 89th-93rd US Colored Infantry on April 4, 1864).

- 5 Regiments of Engineers (1st-5th Corps d'Afrique Engineers, later converted into the 95th-99th US Colored Infantry regiments on April 4, 1864).

- 1 Regiment of Heavy Artillery (later converted into the 10th US Colored (Heavy) Artillery on May 21, 1864).

|

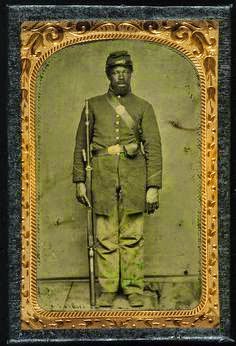

chicago history museum: African American Civil War soldier, c. 1863 |

Right Wing, XVI Corps (1864)

Colored troops served as laborers in the 16th Army Corps' Quartermaster's Department and Pioneer Corps.

- Detachment, Quartermaster's Department.

- Pioneer Corps, 1st Division (Mower), 16th Army Corps.

- Pioneer Corps, Cavalry Division (Grierson), 16th Army Corps.

USCT Regiments

- Notes:6 Regiments of Cavalry [1st-6th USC Cavalry]

- 1 Regiment of Light Artillery [2nd USC (Light) Artillery]

- 1 Independent USC (Heavy) Artillery Battery

- 13 Heavy Artillery Regiments [1st and 3rd-14th USC (Heavy) Artillery]

- 1 unassigned Company of Infantry [Company A, US Colored Infantry]

- 1 Independent USC Company of Infantry [ Southard's Independent Company, Pennsylvania (Colored) Infantry ]

- 1 Independent USC Regiment of Infantry [Powell's Regiment, US Colored Infantry]

- 135 Regiments of Infantry [1st-138th USC Infantry] (The 94th, 105th, and 126th USC Infantry regiments were never fully formed)

- The 2nd USC (Light) Artillery Regiment (2nd USCA) was made up of 9 separate batteries grouped into 3 nominal battalions of three batteries each. The batteries were usually detached.

- I Battalion: A,B & C Batteries.

- II Battalion: D, E & F Batteries.

- III Battalion: G, H & I Batteries.

- The second raising of the 11th USC Infantry (USCI) was created by converting the 7th USC (Heavy) Artillery into an infantry unit.

- The second raising of the 79th USC Infantry (USCI) was formed from the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry.

- The second raising of the 83rd USC Infantry (USCI) was formed from the 2nd Kansas Colored Infantry.

- The second raising of the 87th USCI was formed from merging the first raisings of the 87th and 96th USCI.

- The second raising of the 113th USCI was formed by merging the first raisings of the 11th, 112th, and 113th USCI.

Notable actions

USCT soldiers suffered extra violence at the hands of Confederate soldiers. They were victims of battlefield massacres and atrocities, most notably at Fort Pillow in Tennessee. They were at risk for murder by Confederate soldiers, rather than being held as prisoners of war.[11]USCT regiments fought in all theaters of the war, but mainly served as garrison troops in rear areas. The most famous USCT action took place at the Battle of the Crater during the Siege of Petersburg. Regiments of USCT suffered heavy casualties attempting to break through Confederate lines. Other notable engagements include Fort Wagner, one of their first major tests, and the Battle of Nashville.[11]

The prisoner exchange protocol broke down over the Confederacy's position on black prisoners of war. The Confederacy had passed a law stating that blacks captured in uniform would be tried as slave insurrectionists in civil courts—a capital offense with automatic sentence of death.[12] USCT soldiers were often murdered by Confederate troops without being taken to court. The law became a stumbling block for prisoner exchange.

USCT soldiers were among the first Union forces to enter Richmond, Virginia, after its fall in April 1865. The 41st USCT regiment was among those present at the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. Following the war, USCT regiments served among the occupation troops in former Confederate states.

Awards

Soldiers who fought in the Army of the James were eligible for the Butler Medal, commissioned by that army's commander,Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. In 1861 at Fort Monroe in Virginia, Butler was the first to declare refugee slaves as contraband and refused to return them to slaveholders. This became a policy throughout the Union Army. It started when a few slaves escaped to Butler's lines in 1861 - their owner, a Confederate colonel, came to Butler under a flag of truce and demanded that they be returned to him under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 - Butler informed him that since Virginia claimed to have left the Union, the Fugitive Slave Law no longer applied, and later Butler kept them, declaring the slaves contraband of war.

Eighteen African-American soldiers won the Medal of Honor, the nation's highest award, for service in the war:

- Sergeant William Harvey Carney of the 54th Massachusetts (Colored) Volunteer Infantry was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Battle of Fort Wagner in July 1863. During the advance, Carney was wounded but still went on. When the color-bearer was shot, Carney grabbed the flagstaff and planted it in the parapet, while the rest of his regiment stormed the fortification. When his regiment was forced to retreat, he was wounded two more times while he carried the colors back to Union lines. He did not relinquish it until he handed it to another soldier of the 54th. Carney did not receive his medal until 37 years later.

- 13 African-American soldiers, including Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood and Sergeant Alfred B. Hilton (mortally wounded) of the 4th USCT, were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions at the Battle of Chaffin's Farm in September 1864, during the campaign to take Petersburg.

- Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith of the 55th Massachusetts (Colored) Volunteer Infantry was recommended for the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Battle of Honey Hill in November 1864. Smith prevented the regimental colors from falling into enemy hands after the color sergeant was killed. Due to a lack of official records, was not awarded the medal until 2001.

|

Two unidentified African American Union Army soldiers, full-length portrait, wearing uniforms, c. 1864 |

Postbellum

The USCT was disbanded in the fall of 1865. In 1867 the Regular Army was set at 10 regiments of cavalry and 45 regiments of infantry. The Army was authorized to raise two regiments of black cavalry (the 9th and 10th (Colored) Cavalry) and four regiments of black infantry (the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st (Colored) Infantry), who were mostly drawn from USCT veterans. In 1869 the Regular Army was kept at 10 regiments of cavalry but cut to 25 regiments of Infantry, reducing the black complement to two regiments (the 24th and 25th (Colored) Infantry).

Legacy

The motion picture Glory, starring Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman and Matthew Broderick, portrayed the African-American soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. It showed their training and participation in several battles, including the second assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863.[14] Although the 54th was not a USCT regiment, but a state volunteer regiment originally raised from free blacks in Boston, similar to the 1st and 2nd Kansas Colored Infantry, the film portrays the experiences and hardships of African-American troops during the Civil War.The history of the USCT's wartime contribution was kept alive within the black community by historians such as W. E. B. Du Bois. Since the 1970s and the expansion of historical coverage of minorities, the units and their contributions have been the subject of more books and movies. During the war years, the men had difficulty gaining deserved official recognition for achievement and valor. Often recommendations for decorations were filed away and ignored. Another problem was that the government would mail the award certificate and medal to the recipient, who had to pay the postage due (whether he were white or black). Most former USCT recipients had to return the medals for lack of funds to redeem them.

Legacy and honors

- In September 1996, a national celebration in commemoration of the service of the United States Colored Troops was held.

- The African American Civil War Memorial (1997), featuring Spirit of Freedom by sculptor Ed Hamilton, was erected at the corner of Vermont Avenue and U Street, NW in the capital, Washington, DC. It is administered by the National Park Service.

- In 1999 the African American Civil War Museum opened nearby.

- In July 2011, it celebrated a grand opening of its new museum facility at 1925 Vermont Avenue, just across from the Memorial. It plans four years of related events during the 150th anniversary of the Civil War and the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Movement, to commemorate African-American contributions under the theme: "From the Civil War to Civil Rights".

Numbers of United States Colored Troops by state, North and South

The soldiers are classified by the state where they were enrolled; Northern states often sent agents to enroll ex-slaves from the South. Note that many soldiers from Delaware, DC, Kentucky, Missouri and West Virginia were ex-slaves as well.

| North | Number | South | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 1,764 | Alabama | 4,969 |

| Colorado Territory | 95 | Arkansas | 5,526 |

| Delaware | 954 | Florida | 1,044 |

| District of Columbia | 3,269 | Georgia | 3,486 |

| Illinois | 1,811 | Louisiana | 24,502 |

| Indiana | 1,597 | Mississippi | 17,869 |

| Iowa | 440 | North Carolina | 5,035 |

| Kansas | 2,080 | South Carolina | 5,462 |

| Kentucky | 23,703 | Tennessee | 20,133 |

| Maine | 104 | Texas | 47 |

| Maryland | 8,718 | Virginia | 5,723 |

| Massachusetts | 3,966 | ||

| Michigan | 1,387 | Total from the South | 93,796 |

| Minnesota | 104 | ||

| Missouri | 8,344 | At large | 733 |

| New Hampshire | 125 | Not accounted for | 5,083 |

| New Jersey | 1,185 | ||

| New York | 4,125 | ||

| Ohio | 5,092 | ||

| Pennsylvania | 8,612 | ||

| Rhode Island | 1,837 | ||

| Vermont | 120 | ||

| West Virginia | 196 | ||

| Wisconsin | 155 | ||

| Total from the North | 79,283 | ||

| Total | 178,895 |

United States Colored Troops in Missouri:

Finding African American History at the Missouri State Archives

History of United States Colored Troops

During the Civil War, over 8,000 black Missourians served in the Union Army. They were not treated the same as white soldiers. They were not paid as much and their weapons and uniforms were inferior and of poor quality. But these African American soldiers fought for something they believed in -- freedom from slavery.

The Civil War started on April 12, 1861, at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. Many African American men wanted to fight for the Union. Some were free blacks and others were former slaves. They tried to volunteer at recruiting stations, but were turned away. The Union Army did not want black soldiers.

President Abraham Lincoln had trouble deciding whether to recruit black soldiers. Eleven slave states had already left, or seceded from, the United States. There were four more states that allowed slavery. These four states - Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware - were called "border states" because they were in between the southern states that seceded and the northern states. President Lincoln was afraid that if he allowed black men to fight, thereby emancipating them, those last four slave states would secede, too. He hoped that the war could be won quickly without using African American soldiers.

However, President Lincoln did not realize how hard the Confederate Army would fight. It won several battles, such as Bull Run in Virginia, and Wilson's Creek in southwest Missouri. Many soldiers from both sides were killed and wounded. But Lincoln still would not allow black soldiers to fight.

Some officers thought African Americans should be part of the Union Army. They tried to form regiments of black volunteers to fight, but the War Department forced them to stop.

By July 1862, the United States Congress passed a law allowing African Americans to serve in the Union Army as laborers or cooks or wagon drivers. The law still did not allow black soldiers. But abolitionist General Jim Lane organized a black regiment in Kansas. It was called the 1 st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment. It included former slaves from Missouri, Arkansas, and the Indian Territory. The regiment's first battle was at Island Mound, Missouri, in October 1862. By January 1863, the regiment was mustered into the regular Union Army, and it was renamed the 79 th United States Colored Infantry Regiment (New).

In August 1862, the War Department decided to officially allow the Union Army to recruit African American soldiers. It also said that any slave who fought would be declared free. This meant freedom for their wives and children, too.

Each state recruited its own black soldiers. In early 1864, all the units with African Americans were designated the United States Colored Troops (USCT), with a few exceptions. Each unit in the USCT was assigned a regiment number. The men who enlisted in the USCT came from many different states and backgrounds.

The USCT had an estimated 160 to 170 regiments of infantry, cavalry, heavy artillery, and light artillery. During the Civil War, most regiments consisted of up to 1,000 soldiers. It was hard to keep accurate records. The regiment numbers changed sometimes and some units were deactivated. The total number of African American soldiers is thought to have been between 176,000 and 200,000. There were also African American men and women civilians, perhaps as many as 200,000, who worked as scouts, spies, cooks, teamsters, or chaplains.

The United States Colored Troops made up about ten percent of the U.S. Army during the Civil War. Another 19,000 African Americans served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died in battle or from infection or disease. Though reluctantly accepted into the military, black soldiers consistently proved their courage during the fighting.

Facts About U.S. Colored Troops, and Slave Refugees of Civil War Missouri (and beyond)

During the Civil War, many military units had their own regimental flags they would carry into battle. The units in the United States’ Colored Troops developed their own “battle flags.” This is the flag for the USCT 24th Regiment, Pennsylvania.

This flag was designed by David Bustill Bowser, an African American artist from Philadelphia who also created several other designs for USCT banners. He also painted Lincoln and a famous portrait of John Brown.

1) Only men ages 18 to 45, of good health and physical condition could enlist in the U.S. Colored Troops. Before December 1863, Missouri slaves of loyal masters needed consent before enrolling.

2) The first colored regiment organized in the State of Missouri was the 3rd Arkansas Infantry (African Descent). It was composed of primarily Missourians but because of prejudice the State did not want to claim them as their own. The unit was composed of freemen and slaves of master's loyal to the Union. They began recruitment on shortly after May 22, 1863 and were organized Aug 12, 1863 at Schofield Barracks, St. Louis, Mo. They were redesignated the 56th U.S. Colored Troops on March 11, 1864. Most of their service was garrison duty at Helena, Arkansas but they did go on two nearby expeditions. The regiment lost a whopping 674 men. 25 killed; 649 died of disease. It remained on duty at Helena till mustered out, Sept. 15, 1866.

3) Missouri was the first State to see Colored Troops in combat. At Island Mound, Missouri in the western part of the state, the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry saw action against Confederates (Oct. 29, 1862). [Kansas was a bit premature in forming this unit according to Federal law. Most of the men of this regiment were former slaves from Arkansas and Missouri. Out of convenience, the owners of these slaves were assumed to be all disloyal.] A detail of soldiers of this unit went out on picket duty and were separated from the main part of the regiment. They took refuge in a ravine and held their ground. Capt. Richard Ward who commanded these troops stated, "I have witnessed some hard fights, but I never saw a braver sight than that handful of brave men fighting...Not one surrendered or gave up a weapon." One of the Confederates reported that "The black devils fought like tigers...not one would surrender, though they had tried to take a prisoner."

4) Originally the slaveowner's consent was required before a slave could enlist. Order No. 135 of Nov. 1863 changed this, allowing enlistment without consent. If the owner did consented they were given some compensation. In addition, the order abolished the highly effective recruitment patrols. There was some dispute that these patrols were forcing some slaves against their will. Certainly they were opposed by most slaveowners. Unfortunately the change required slaves willing to enlist, to travel to the recruitment stations, sometimes many miles away..

5) Runaway slaves seeking to enlist had to overcome many risks on their journey. Slave Patrols, bushwhackers, and guerrillas.

6) If a runaway slave made it to the recruiting station (usually the office of the Provost Marshall), he still could be rejected due to poor health or physical condition. If rejected he became a refugee and if outside of the contraband camps, risked danger of being captured by a slave patrol.

7) Men of the U.S. Colored Troops often escaped from master's that disapproved of blacks being soldiers. After they enlisted, if their families were not in the contraband camp, sometimes masters abused. their wives or children in retaliation..

8) Some families of soldiers were sold as revenge for slave joining the Army. Usually slaves were sold to Kentucky were it was also a protected institution.

9) On Nov 10, 1863, Gen. John M. Schofield issued Special Order 307, an order that prohibited the selling of slaves from the State. A month later he modified it allowing the sale of any slave unfit for military service.

10) Most U.S. Colored Regiments were assigned Post and Garrison Duty or labor on fortifications. This included guarding Confederate prisoners of war. When they saw action they demonstrated that they could fight as well as white troops.

11) Missouri ranked 4th of the Union States, in regard to the number of Colored troop enlistments (8,344). This represents 39 percent of the prewar black males (21,167), age 18 to 45.

12) In addition to Missouri units, many black Missourians served in regiments of other States. Most of the Kansas Colored Troops (2,080) were from runaway or abducted slaves from Missouri. (Kansas' prewar black male population was only 126, age 18 to 45.) Also Eastern recruiters often came to St. Louis looking to enlist black Missourians. Some joined units as far away as Massachusetts.

13) Four companies (Co. G, H, I, K) of the 1st Iowa Colored Troops (60th U.S. Colored Infantry) were composed of Missourians. The regiment finished its organization at Benton Barracks in St. Louis, Mo. Iowa could only claim 440 men of this regiment and of this number, many were former Missouri slaves. Iowa's prewar male population of military age was only 249.

14) Four regiments were organized at Benton Barracks, St. Louis, Mo. These were the following:

- 1st Missouri Colored Infantry (62nd U.S. Colored Infantry)

- 2nd Missouri Colored Infantry (65th U.S. Colored Infantry)

- 3rd Missouri Colored Infantry (67th U.S. Colored Infantry)

- 4th Missouri Colored Infantry (68th U.S. Colored Infantry)

15) Colored Troops had separate hospital wards at Benton Barracks. Nurses were staffed by the Colored Ladies Union Aid Society.

16) Not all the troops at Benton Barracks experienced good treatment from the government. Lt. Col. William F. Fox, U.S.V. reported that for the 2nd Missouri Colored Infantry,"Over 100 men died at [Benton] Barracks before the regiment took the field, the men having been enlisted by the Provost-Marshals throughout the State and forwarded to this Post during an inclement season,-- thinly clad, and many of them hatless, shoeless, and without food. Many suffered amputation of frozen feet or hands, and the diseases engendered by this exposure resulted in a terrible and unprecedented mortality."

17) A contraband camp of former slaves was also located at Benton Barracks, north of the City of St. Louis (in present location of Fairgrounds Park in present day north St. Louis). During the summer of 1863, St. Louis was inundated by thousands of refugee slaves. The government had no way to determine which of these individuals were slaves or "freedmen", thus they were all treated as freedmen. On certain occasions slave owners (or slave catchers) tried to retrieve their subjects, but Union guards would only allow slaves to go willingly and without abuse.

18) Colored Troops went long periods of time without pay. Rarely were they able to send money back to help their families. Men who were rejected for service in the Army were anxious to work for money instead. James E. Yeatman of the Western Sanitary Commission (a forerunner of the Red Cross) gave this description: "Besides the fact that men are thus pressed into service, thousands have been employed for weeks and months, who have never received any thing but promises to pay. This negligence and failure to comply with obligations, have greatly disheartened the poor slave, who comes forth at the call of the President, and supposes himself a free man, and that, by leaving his rebel master, he is inflicting a blow on the enemy, ceasing to labor and to provide food for him and for the armies of the rebellion. Thus he was promised freedom, but how is it with him ? He is seized in the street, and ordered to go and help unload a steamboat, for which he will be paid, or to sent to work in the trenches, or to labor for some quartermaster, or to chop wood for the Government. He labors for months, and at last is only paid with promises, unless perchance it may be with kicks, cuffs, and curses."

19) Life at the contraband camps was very harsh for the families of soldiers. Yeatman: "The poor negroes are everywhere greatly depressed at their condition. They all testify that if they were only paid their little wages as they earn them, so they could purchase clothing, and were furnished with the provisions promised, they could stand it; but to work and get poorly paid, poorly fed, and not doctored when sick, is more than they can endure. Among the thousands whom I questioned, none showed the least unwillingness to work. If they could only be paid fair wages, they would be contented and happy. They do not realize that they are taken and hired out to men who treat them, so far as providing for them is concerned, far worse than their "secesh" masters did. Besides this they feel that their pay or hire is lower now than it was when the "secesh" used to hire them. This is true."

20) In wartime Missouri, no matter what Congress says, there were no guarantees for former slaves. "...Every day blacks and colored people of all shades--men, women, and children--are thrown into it, who had believed in the gospel of liberty...We spoke to an old soldier of the Twelfth Regiment [Colored Troops], who had carried a musket in the service of liberty since the commencement of the war...A negro who has gone through all the toils of the Twelfth Regiment for two years is now a fugitive slave in the jail, caught on Lincoln's slave-hunting ground in Missouri......who has given our Provost-Marshal-General Broadhead authority to recall and declare null and void the free papers which have been given by his predecessors or by former commanders of this department to the slaves of rebel masters? Does a slave become a free man by a certificate of liberty, duly made out by competent authority, or is such a certificate of liberty a mere piece of paper, which may be torn up at pleasure? [--Spirit of the German Press, The Westliche Post. Article in Official Records, Maj. Gen. J. M. Schofield, dated Saint Louis, September 20, 1863]

21) The highest ranking black was Martin R. Delaney, commissioned a Major and "graduate of the Harvard Medical School and the first Negro field officer to serve in the Civil War." He served in the 104th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops. [The New York Times, Mar.1, 1865]

22) Lincoln University of Missouri (Jefferson City) was founded in 1866 by officers and men of the 62nd and 65th U.S. Colored Troops.

The following facts on U.S. Colored Troops was authored by the National Archives:

1) "179,000 black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy."

2) "Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war—30,000 of infection or disease"

3) In 1863 the Confederate Congress threatened to punish severely officers of black troops and to enslave black soldiers. As a result, President Lincoln issued General Order 233, threatening reprisal on Confederate prisoners of war (POWs) for any mistreatment of black troops. Although the threat generally restrained the Confederates, black captives were typically treated more harshly than white captives..

4) Black soldiers were initially paid $10 per month from which $3 was automatically deducted for clothing, resulting in a net pay of $7. In contrast, white soldiers received $13 per month from which no clothing allowance was drawn.

5) In June 1864 Congress granted equal pay to the U.S. Colored Troops and made the action retroactive. Black soldiers received the same rations and supplies. In addition, they received comparable medical care.

6) Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all non-combat support functions that sustain an army, as well. Black carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters also contributed to the war cause.

6) Because of prejudice against them, black units were not used in combat as extensively as they might have been. Nevertheless, the soldiers served with distinction in a number of battles. Black infantrymen fought gallantly at Milliken's Bend, LA; Port Hudson, LA; Petersburg, VA; Nashville, TN" (and the assault on Fort Wagner, SC by the 54th Massachusetts.)

For more on Slavery and the Civil War in Missouri, see my other article, "Slavery in St. Louis".

U.S. Colored Troops and Sailor Awarded Medal of Honor

APPLETON, WILLIAM H.

Rank and organization: First Lieutenant, Company H, 4th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Petersburg, Va., 15 June 1864; At New Market Heights, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: Portsmouth, N.H. Born: 24 March 1843, Chichester, N.H. Date of issue: 18 February 1891. Citation: The first man of the Eighteenth Corps to enter the enemy's works at Petersburg, Va., 15 June 1864. Valiant service in a desperate assault at New Market Heights, Va., inspiring the Union troops by his example of steady courage

BARNES, WILLIAM H.

Rank and organization: Private, Company C, 38th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at:------. Birth: St. Marys County, Md. Date of issue 6 April 1865. Citation: Among the first to enter the enemy's works; although wounded.

BARRELL, CHARLES L.

Rank and organization: First Lieutenant, Company C, 102d U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: Near Camden, S.C., April 1865. Entered service at: Leighton, Allegan County, Mich. Birth:------. Date of issue: 14 May 1891. Citation: Hazardous service in marching through the enemy's country to bring relief to his command.

BATES, DELAVAN

Rank and organization: Colonel, 30th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Cemetery Hill, Va., 30 July 1864. Entered service at: Oswego County, N.Y. Born: 1840, Schoharie County, N.Y. Date of issue: 22 June 1891. Citation: Gallantry in action where he fell, shot through the face, at the head of his regiment.

BEATY, POWHATAN

Rank and organization: First Sergeant, Company G, 5th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: Delaware County, Ohio. Birth: Richmond, Va. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Took command of his company, all the officers having been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it.

BENNETT, ORSON W.

Rank and organization: First Lieutenant, Company A, 102d U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Honey Hill, S.C., 30 November 1864. Entered service at: Michigan. Born: 17 November 1841, Union City Branch County, Mich. Date of issue: 9 March 1887. Citation: After several unsuccessful efforts to recover 3 pieces of abandoned artillery, this officer gallantly led a small force fully 100 yards in advance of the Union lines and brought in the guns, preventing their capture.

BLAKE, ROBERT

Rank and organization: Contraband, U.S. Navy. Entered service at: Virginia. G.O. No.: 32, 16 April 1864. Accredited to: Virginia. Citation: On board the U.S. Steam Gunboat Marblehead off Legareville, Stono River, 25 December 1863, in an engagement with the enemy on John's Island. Serving the rifle gun, Blake, an escaped slave, carried out his duties bravely throughout the engagement which resulted in the enemy's abandonment of positions, leaving a caisson and one gun behind.

BRONSON, JAMES H.

Rank and organization: First Sergeant, Company D, 5th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: Delaware County, Ohio. Birth: Indiana County, Pa. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Took command of his company, all the officers having been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it.

BRUSH, GEORGE W.

Rank and organization: Lieutenant, Company B, 34th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Ashepoo River, S.C., 24 May 1864. Entered service at: New York. Born: 4 October 1842, West Kill, N.Y. Date of issue: 21 January 1897. Citation: Voluntarily commanded a boat crew, which went to the rescue of a large number of Union soldiers on board the stranded steamer Boston, and with great gallantry succeeded in conveying them to shore, being exposed during the entire time to heavy fire from a Confederate battery.

DAVIDSON, ANDREW

Rank and organization: First Lieutenant, Company H, 30th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At the mine, Petersburg, Va., 30 July 1864. Entered service at: Otsego County, N.Y. Born: 12 February 1840, Scotland. Date of issue: 17 October 1892. Citation: One of the first to enter the enemy's works, where, after his colonel, major, and one-third the company officers had fallen, he gallantly assisted in rallying and saving the remnant of the command.

DORSEY, DECATUR

Rank and organization: Sergeant, Company B, 39th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Petersburg, Va., 30 July 1864. Entered service at: Baltimore County, Md. Birth: Howard County, Md. Date of issue: 8 November 1865. Citation: Planted his colors on the Confederate works in advance of his regiment, and when the regiment was driven back to the Union works he carried the colors there

and bravely rallied the men.

EDGERTON, NATHAN H.

Rank and organization: Lieutenant and Adjutant, 6th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: Philadelphia, Pa. Birth: ------. Date of issue: 30 March 1898. Citation: Took up the flag after 3 color bearers had been shot down and bore it forward, though himself wounded.

EVANS, IRA H.

Rank and organization: Captain, Company B, 116th U.S. Colored Troops, Place and date: At Hatchers Run, Va., 2 April 1865. Entered service at: Barre, Vt. Born: 11 April 1844, Piermont, N.H. Date of issue: 24 March 1892. Citation: Voluntarily passed between the lines, under a heavy fire from the enemy, and obtained important information.

FLEETWOOD, CHRISTIAN A.

Rank and organization: Sergeant Major, 4th U.S. Colored Troops, Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: ------. Birth: Baltimore, Md. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Seized the colors, after 2 color bearers had been shot down, and bore them nobly through the fight.

GARDINER, JAMES

Rank and organization: Private, Company I, 36th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at:------. Birth: Gloucester, Va. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Rushed in advance of his brigade, shot a rebel officer who was on the parapet rallying his men, and then ran him through with his bayonet.

HARRIS, JAMES H.

Rank and organization: Sergeant, Company B, 38th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At New Market Heights, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at:------. Birth: St. Marys County, Md. Date of issue: 18 February 1874. Citation: Gallantry in the assault.

HAWKINS, THOMAS R.

Rank and organization: Sergeant Major, 6th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: Philadelphia, Pa. Birth: Cincinnati, Ohio. Date of issue: 8 February 1870. Citation: Rescue of regimental colors.

HILTON, ALFRED B.

Rank and organization: Sergeant, Company H, 4th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date. At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at:------. Birth: Harford County, Md. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: When the regimental color bearer fell, this soldier seized the color and carried it forward, together with the national standard, until disabled at the enemy's inner line.

HOLLAND, MILTON M.

Rank and organization: Sergeant Major, 5th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: Athens, Ohio. Born: 1844, Austin, Tex. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Took command of Company C, after all the officers had been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it.

JAMES, MILES

Rank and organization: Corporal, Company B, 36th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 30 September 1864. Entered service at: Norfolk, Va. Birth: Princess Anne County, Va. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Having had his arm mutilated, making immediate amputation necessary, he loaded and discharged his piece with one hand and urged his men forward; this within 30 yards of the enemy's works.

KELLY, ALEXANDER

Rank and organization: First Sergeant, Company F, 6th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: ------. Birth. Pennsylvania. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Gallantly seized the colors, which had fallen near the enemy's lines of abatis, raised them and rallied the men at a time of confusion and in a place of the greatest danger.

MERRIAM, HENRY C

Rank and organization: Lieutenant Colonel, 73d U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Fort Blakely, Ala., 9 April 1865. Entered service at: Houlton, Maine. Birth: Houlton, Maine. Date of issue: 28 June 1894. Citation: Volunteered to attack the enemy's works in advance of orders and, upon permission being given, made a most gallant assault.

NICHOLS, HENRY C.

Rank and organization: Captain, Company E, 73d U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Fort Blakely, Ala., 9 April 1865. Entered service at: ------. Birth: Brandon, Vt. Date of issue: 3 August 1897. Citation: Voluntarily made a reconnaissance in advance of the line held by his regiment and, under a heavy fire, obtained information of great value.

PINN, ROBERT

Rank and organization: First Sergeant, Company I, 5th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: Massillon, Ohio. Born: 1 March 1843, Stark County, Ohio. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Took command of his company after all the officers had been killed or wounded and gallantly led it in battle.

RATCLIFF, EDWARD

Rank and organization: First Sergeant, Company C, 38th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: ------. Birth: James County, Va. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation. Commanded and gallantly led his company after the commanding officer had been killed; was the first enlisted man to enter the enemy's works.

THORN, WALTER

Rank and organization: Second Lieutenant, Company G, 116th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Dutch Gap Canal, Va., 1 January 1865. Entered service at:------. Birth: New York, N.Y. Date of issue: 8 December 1898. Citation: After the fuze to the mined bulkhead had been lit, this officer, learning that the picket guard had not been withdrawn, mounted the bulkhead and at great personal peril warned the guard of its danger.

VEAL, CHARLES

Rank and organization: Private, Company D, 4th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: Portsmouth, Va. Birth: Portsmouth Va. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation: Seized the national colors after 2 color bearers had been shot down close to the enemy's works, and bore them through the remainder of the battle.

WRIGHT, ALBERT D.

Rank and organization: Captain, Company G, 43d U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Petersburg, Va., 30 July 1864. Entered service at:------. Born: 10 December 1844, Elkland, Tioga County, Pa. Date of issue: 1 May 1893. Citation: Advanced beyond the enemy's lines, capturing a stand of colors and its color guard; was severely wounded.

Brief Regimental Histories of Units with a Significant Number of Missourians Present:

3rd REGIMENT ARKANSAS INFANTRY (AFRICAN DESCENT).

Organized at St. Louis, Mo., August 12, 1863. Attached to District of Eastern Arkansas, Dept. Arkansas, to January, 1864. Little Rock, Ark., 7th Army Corps, Dept. Ark., to March, 1864.

SERVICE.--Ordered to Helena, Ark., and Post duty there and at Little Rock till March, 1864. Expedition from Helena up White River February 4-8, 1864, and up St. Francis River February 13-14.Designation of Regiment changed to 56th U.S. Colored Troops March 11, 1864.

1st REGIMENT COLORED KANSAS INFANTRY.

Organized at Fort Scott and mustered in as a Battalion January 13, 1863. Attached to Dept. of Kansas to June, 1863. District of the Frontier, Dept. Missouri, to January, 1864. Unattached, District of the Frontier, 7th Corps, Dept. of Arkansas, to March, 1864. 2nd Brigade, District of the Frontier, 7th Corps, to December, 1864.

SERVICE.--Duty in the Dept. of Kansas October, 1862, to June, 1863. Action at Island Mound, Mo., October 27, 1862. Island Mound, Kansas, October 29. Butler, Mo., November 28. Ordered to Baxter Springs May, 1863. Scout from Creek Agency to Jasper County, Mo., May 16-19 (Detachment). Sherwood, Mo., May 18. Bush Creek May 24. Near Fort Gibson May 28. Shawnee town, Kan., June 6 (Detachment). March to Fort Gibson, C. N., June 27-July 5, with train. Action at Cabin Creek July 1-2. Elk Creek near Honey Springs July 17. At Fort Gibson till September. Lawrence, Kan. July 27 (Detachment). Near Sherwood August 14 Moved to Fort Smith, Ark., October, thence to Roseville December, and duty there till March, 1864. Horse Head Creek February 12, 1864. Roseville Creek March 20. Steele's Camden Expedition March 23-May 3. Prairie D'Ann April 9-12. Poison Springs April 18. Jenkins Ferry April 30. March to Fort Smith, Ark., May 3-16, and duty there till December. Fort Gibson, C. N. September 16. Cabin Creek September 19. Timber Hill November 19. Designation of Regiment changed <dy_1187> to 79th U.S. Colored Troops December 13, 1864, which see.

1st REGIMENT MISSOURI COLORED INFANTRY.

Organized at Benton Barracks, Mo., December 7-14, 1863. Attached to District of St. Louis, Mo., to January, 1864. Ordered to Port Hudson, La. Designation changed to 62nd Regiment United States Colored Troops March 11, 1864

2nd REGIMENT MISSOURI COLORED INFANTRY.

Organized at Benton Barracks December 18, 1863, to January 16, 1864. Duty there till March, 1864. Designation changed to 65th Regiment United States Colored Troops March 11, 1864 .

3rd REGIMENT MISSOURI COLORED INFANTRY.

Organized at Benton Barracks, Mo. Designation changed to 67th United States Colored Troops March 11, 1864

4th REGIMENT MISSOURI COLORED INFANTRY.

Organized at Benton Barracks, Mo. Designation changed to 68th United States Colored Troops March 11, 1864

56th REGIMENT INFANTRY.

Organized March 11, 1864, from 3rd Arkansas Infantry (African Descent). Attached to District of Eastern Arkansas, 7th Corps, Dept. of Arkansas, to August, 1865. Dept. of Arkansas to September, 1866.

SERVICE.--Post and garrison duty at Helena, Ark., till February, 1865. Action at Indian Bay April 13, 1864. Muffleton Lodge June 29. Operations in Arkansas July 1-31. Wallace's Ferry, Big Creek, July 26. Expedition from Helena up White River August 29-September 3. Expedition from Helena to Friar's Point, Miss., February 19-22, 1865. Duty at Helena and other points in Arkansas till September, 1866. Mustered out September 15, 1866. Regiment lost during service 4 Officers and 21 Enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 2 Officers and 647 Enlisted men by disease. Total 674.

60th REGIMENT INFANTRY.

Organized March 11, 1864, from 1st Iowa Colored Infantry. Attached to District of Eastern Arkansas, 7th Corps, Dept. of Arkansas, to April, 1865. 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, 7th Corps, to August, 1865. Dept. of Arkansas to October, 1865.

SERVICE.--Post and garrison duty at Helena, Ark., till April, 1865. Expedition from Helena to Big Creek July 25, 1864. Action at Wallace's Ferry, Big Creek, July 26. Expedition to Kent's Landing August 11-13. Expedition up White River August 29-September 3 (Cos. "C" and "F"). Scout to Alligator Bayou September 9-14 (Detachment). Scouts to Alligator Bayou September 22-28 and October 1-4. Expedition to Harbert's Plantation, Miss., January 11-16, 1865 (Co. "C"). Moved to Little Rock April 8, 1865, and duty there till August 20. Moved to Duvall's Bluff, thence to Jacksonport, Ark. Duty there and at various points in Sub-District of White River, in White, Augusta, Franklin and Fulton Counties, Powhatan on Black River and at Batesville till September. Mustered out at Duvall's Bluff October 15, 1865. Discharged November 2, 1865.

62nd REGIMENT INFANTRY.

Organized March 11, 1864, from 1st Missouri Colored Infantry. Attached to District of St. Louis, Dept. of Missouri, to March, 1864. District of Baton Rouge, La., Dept. of the Gulf, to June, 1864. Provisional Brigade, District of Morganza, Dept. of the Gulf, to September, 1864. 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, United States Colored Troops, District of Morganza, Dept. of the Gulf, to September, 1864. Port Hudson, La., Dept. of the Gulf, to September, 1864. Brazos Santiago, Texas, to October, 1864. 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, United States Colored Troops, Dept. of the Gulf, to December, 1864. Brazos Santiago, Texas, to June, 1865. Dept. of Texas to March, 1866.

SERVICE.--Ordered to Baton Rouge, La., March 23, 1864, and duty there till June. Ordered to Morganza, La., and duty there till September. Expedition from Morganza to Bayou Sara September 6-7. Ordered to Brazos Santiago, Texas, September, and duty there till May, 1865. Expedition from Brazos Santiago May 11-14. Action at Palmetto Ranch May 12-13, 1865. White's Ranch May 13. Last action of the war. Duty at various points in Texas till March, 1866. Ordered to St. Louis via New Orleans, La. Mustered out March 31, 1866.

65th REGIMENT INFANTRY.

Organized March 11, 1864, from 2nd Missouri Colored Infantry. Attached to Dept. of Missouri to June, 1864. Provisional Brigade, District of Morganza, La., Dept. of the Gulf, to September, 1864. 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, United States Colored Troops, District of Morganza, Dept. of the Gulf, to February, 1865. 1st Brigade, 1st Division, United States Colored Troops, District of Morganza, La., Dept. of the Gulf, to May, 1865. Northern District of Louisiana and Dept. of the Gulf to January, 1867.

SERVICE.--Garrison duty at Morganza, La., till May, 1865. Ordered to Port Hudson, La. Garrison duty there and at Baton Rouge and in Northern District of Louisiana till January, 1867. Mustered out January 8, 1867. Regiment lost during service 6 Officers and 749 Enlisted men by disease.

67th REGIMENT INFANTRY.

Organized March 11, 1864, from 3rd Missouri Colored Infantry. Attached to Dept. of Missouri to March, 1864. District of Port Hudson, La., Dept. of the Gulf, to June, 1864. Provisional Brigade, District of Morganza, Dept. of the Gulf, to September, 1864. 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, United States Colored Troops, District of Morganza, Dept. of the Gulf, to February, 1865. 1st Brigade, 1st Division, United States Colored Troops, District of Morganza, Dept. of the Gulf, to May, 1865. Northern District of Louisiana, Dept. of the Gulf, to July, 1865.

SERVICE.--Moved from Benton Barracks, Mo., to Port Hudson, La., arriving March 19, 1864, and duty there till June. Moved to Morganza, La., and duty there till June, 1865. Action at Mt. Pleasant Landing, La., May 15, 1864 (Detachment). Expedition from Morganza to Bayou Sara September 6-7, 1864. Moved to Port Hudson June 1, 1865. Consolidated with 65th Regiment, United States Colored Troops, July 12, 1865.

68th REGIMENT INFANTRY.

Organized March 11, 1864, from 4th. Missouri Colored Infantry. Attached to District of Memphis, Tenn., 16th Corps, Dept. of the Tennessee, to June, 1864. 1st Colored Brigade, Memphis, Tenn., District of West Tennessee, to December, 1864. Fort Pickering, Defences of Memphis, Tenn., District of West Tennessee, to February, 1865. 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, United States Colored Troops, Military Division West Mississippi, to May, 1865. 1st Brigade, 1st Division, United States Colored Troops, District of West Florida, to June, 1865. Dept. of Texas to February, 1866.

SERVICE.--At St. Louis, Mo., till April 27, 1864. Ordered to Memphis, Tenn., and duty in the Defences of that city till February, 1865. Smith's Expedition to Tupelo, Miss., July 5-21, 1864. Camargo's Cross Roads, near Harrisburg, July 13. Tupelo July 14-15. Old Town Creek July 15. At Fort Pickering, Defences of Memphis, Tenn., till February, 1865. Ordered to New Orleans, La., thence to Barrancas, Fla. March from Pensacola, Fla., to Blakely, Ala., March 20-April 1. Siege of Fort Blakely April 1-9. Assault and capture of Fort Blakely April 9. Occupation of Mobile April 12. March to Montgomery April 13-25. Duty there and at Mobile till June. Moved to New Orleans, La., thence to Texas. Duty on the Rio Grande and at various points in Texas till February, 1866. Mustered out February 5, 1866.

79th REGIMENT INFANTRY.--(NEW.)

Organized from 1st Kansas Colored Infantry December 13, 1864. Attached to 2nd Brigade, District of the Frontier, 7th Corps, Dept. of Arkansas, to January, 1865. Colored Brigade, 7th Corps, to February, 1865. 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, 7th Corps, to August, 1865. Dept. of Arkansas to October, 1865.

SERVICE.--Duty at Fort Smith, Ark., till January, 1865. Skirmish at Ivey's Ford January 8. Ordered to Little Rock January 16. Skirmish at Clarksville, Ark., January 18. Duty at Little Rock, Ark., till July, and at Pine Bluff till October. Mustered out at Pine Bluff, Ark., October 1, 1865, and discharged at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, October 30, 1865.

Regiment lost during service 5 Officers and 183 Enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 1 Officer and 165 Enlisted men by disease. Total 354.

What About Black Confederates ?

Across the South there was a significant minority of slaves and freemen that sided with the Confederacy. Some were promised freedom others were doing it because they believed it was their duty to defend their native States from invaders. This does not mean they were fighting to preserve slavery.

For free blacks in Missouri, the Confederacy had nothing to offer to rally them to their cause. A dozen or so rode with Confederate guerilla forces of Quantrill and a few served elsewhere. Their numbers in Missouri do not compare with the visibility of black Confederate in other southern States. Please see the author's article on Black Confederates in the Civil War for more information.

1 comment:

I have never heard or found any supporting evidence that "in Missouri, since most slave owners were pro-Union." On the contrary, I have found in the large slave owning areas of Missouri's slave owners fought for or had sons in Confederate service. For example, Missouri's Governor C. F. Jackson, who became Missouri's first Confederate Governor, was a large slave owner in Saline County. Prior to moving to Saline he owned a plantation near Fayette, which is still standing to this day. Confederate General John Sappington Marmaduke grew up on his father’s plantation not far from where Gov . C. F. Jackson lived. Both of Missouri’s Confederate Generals Shelby and Price owned plantations with dozens of slaves, Shelby in Lafayette and Price in Chariton. I can provide you with dozens of names of Missouri slave owners who supported the South and are from counties found along the Missouri River from Platte County to Callaway and across the rest of the State’s Little Dixie region. Local Missouri Little Dixie County histories recount the thousands of names of those who served for the Confederate, which also match the local 1860 Federal Slave census in Missouri as slave owners. So, your statement is baseless and unfortunate, because I found much of the information on these pages interesting.

Post a Comment