Post Civil War Vigilante Mobs Hang Eight White Men and Shoot 1 Dead around Warrensburg-Fayetteville, MO 1866-67

The facts of the murder are about as follows: Two men called at the residence or house, which was occupied by two families; that of Mr. Sweitzer, consisting of a wife and five children, and one room occupied by Mr. Younger and wife. One of the men was dressed in soldier's clothes, tall, black hair, and dark complexion. The other was heavy, low stature, and dressed in citizens' costume. Both attempted to disguise, but parties that had met them once could hardly fail to recognize that pair. They entered the room occupied by Mr. Younger, feigned drunkenness, and asked them if they could stay all night. They were told that the house was crowded, and that no stranger could be entertained. In the more infernal hue, than damned assassination." The robbers and murderers rifled the murdered man's pockets, and fled, leaving them alone, the living with the dead. There came a long night of watching, weeping, and praying. “You had no children, butchers; if you had, the thought of them would have stirred up remorse." But they were left with curses: the mother a widow, the children fatherless; that husband and father lying dead before them, slain by assassins, who had been petted and encouraged in their infamous crimes so long, that they defied the laws of God and man, forgetting that the former had said, "Thou shalt not kill," and that the latter demanded life for life. So the hours wore away- Who can imagine the horror of that night, when darkness lent his robe to monster fear: And heaven's black mantle banishing the light, Made everything in ugly form appear. Mr. Sweitzer had in his possession about $130, which they succeeded in carrying off; though in their fright they must have been careless of the booty, as $120 dollars of the money taken, was found in the road the next morning near Hazel Hill. Sweitzer, a short time previous to his death, had purchased a farm in the nation, and was to make a payment on the same about the time of his death. The robbers, no doubt, thinking he had a large sum of money, went to the house for the purpose of securing the same, and, finding they could not obtain it without bloodshed, resorted to the killing as described above. We will leave the family of Mr. Sweitzer to their melancholy fate, and follow the murderers. After leaving the house they met Mr. Jack Redford, and fired several shots at him, killing his horse, which was found dead by the roadside next morning. It is supposed they attempted to take the life of Redford to prevent detection. But “Murder will out." Other sins only speak; murder shrieks out; the element of water moistens the earth, but blood flies upwards, and bedews the heavens. Early next morning the news had spread, and parties were suspected. Sullen, methinks, and slow the morning breaks, As if the sun were listless to appear, And dark designs hang heavy on the day. It was the morning of February 28, 1867. The storm was dead; the clouds, one by one, drifted away, leaving the sky mirror-like. The rain of the previous night congealed as it fell, and when day broke all was in ice. The trees were bending under their burdens; millions and millions of icicles hung from every tree, shrub and twig of our great forests; each blade of grass and tiny weed wore a coat of crystal. The rising sun shot its rays through this beautiful glistening mass, and was reflected and thrown back in variegated colors by the millions of glittering beauties that hung so feebly from the trees. Everything wore a glittering coat, the forests resembled trees, shrubs and logs of ice. The ground was clothed-not in a mantle of white, but a robe of crystal. It was grand, glittering and glorious, but not of long duration-born of night, lived but a day, and vanished. As the sun rose heavenward, and the air became warm, the ice began to melt and fall. In a short time nothing could be heard but breaking and falling ice, everything so tastily robed in gorgeous costume was fast becoming bare and ragged. One could only look on and silently admire the splendors of nature. Amid this decaying beauty rode a solitary horseman, his powerful horse, heavily ironed, plowed up the ice, as he cantered over its smooth surface. The rider sat erect in the saddle, and moved gracefully with every motion of the horse, showing plainly that he was an accomplished horseman. He stood about six feet four inches in height, and weighed about one hundred and sixty-five pounds. He wore a soldier's costume, with a navy revolver at each side. His hair, long, black and inclined to curl, was thrown carelessly back from a broad, dark, swarthy brow. On his upper lip he wore a carefully trained mustache, black as jet; nose, slightly Roman, and eyes dark, restless and piercing. He looked on me with dangerous eye-glance, showing his nature in his countenance; His rolling eyes did never rest in place, but walked each where for fear of hid mischance, holding a lattice before his face, through which he did but peep as forward he did pace.

Although he attempted to disguise himself, he was known. It was Dick Sanders, the outlaw. The news of the murder had reached town early in the morning, and everything was excitement. Our citizens were determined to submit no longer to such fiendish outrages-every breast was filled with horror and indignation-personalities and political differences were forgotten, or laid aside. There was no prejudice in the matter. With one voice they swore to avenge the death of Sweitzer, and exterminate the murders and thieves that had so long ruled the destinies of our people, and carried death and destruction into so many peaceful homes. They were at last unmasked, and were no longer to carry out their infamous crimes under the cover of the “Bonny Blue," or urge their heartless companions on with the wolf cry of rebels, while, on the other hand, peaceable and law-abiding citizens were shot down and robbed as southern sympathizers. Leading men, who encouraged them, trembled. The masses were aroused. No man dare say, "Stop." It was like the gathering of a fearful storm. Muttering thunders could be heard from every quarter of the county. At night it would come and like a mighty avalanche, tearing loose from some Alpine height, would sweep everything before it. That day will long be remembered. It was fearful. Low conversation, silent preparation, a gradual gathering of men, the return and departure of couriers, in quick succession, all indicated the storm was about to break forth in all its fury. A meeting was called at the court house, at one o'clock, to take into consideration the best and surest way of ridding our county of the band of marauders that made it their headquarters.

At the appointed time there were over 400 men there. The house was organized by calling Col. Isaminger to the chair, and N. B. Klaine to act as secretary. Prof. Biggar was called and approved the object of the meeting. He said: "It is our duty to ferret out the murderers of our peaceable citizen, who has so lately been killed, and bring them to justice. Murderers may any day walk our streets with safety, and it is necessary that we engage detectives. We have not the same advantages that larger cities enjoy, and whatever action is taken now, is for our safety. I am opposed to summary vengeance, but when law cannot be enforced, and violators brought to justice, it is necessary for the people to take the matter in hand. The right of the people to take care of themselves, if the law does not, is an indisputable right. We must unite and put down lawlessness." Rev. J. W. Newcomb was next called and said: "The meeting has my hearty approval. The sentiments expressed by Mr. Biggar are my own. 'He that draweth the sword shall perish by the sword,' and as exemplified in this case, men who discard law and order, have to be met perpetrators of murders and robberies to justice, and

WHEREAS; The greatest of crimes are becoming more and more frequent and punishment less and less certain; therefore, Resolved, That we, the people of the town of Warrensburg, and of the county of Johnson, without distinction of party, do pledge ourselves that we will, to the extent of our ability, assist in the discovery of the perpetrators of all murders and robberies, and will assist the officers of justice in detecting and punishing them; and as the civil law proves inadequate to bring such criminals to justice, therefore, Resolved, That we will support a vigilance committee, in executing summarily,' all murderers, robbers and horse thieves, wherever they can be identified with reasonable certainty, believing, as we do, that self-preservation is the first law of nature, and that the citizens of a county are justified in administering justice to such criminals, wherever the duly constituted authorities from any cause whatever, are unable or fail to do so.

Sanders was present during the meeting, but the instant it adjourned, disappeared. The committee organized, and by nine o'clock were on the march. "Hark! Peace! It was the owl that shrieked, the fatal bell-man, which gives the sternest good night," Night had again spread her black mantle over our half of the earth. The weather had moderated, the wind was soft and damp. The roads were soft and sloppy and disagreeable, it was nine o'clock. The Warrensburg committee consisted of about one hundred of our best citizens. They were joined at Fayetteville by the Fayetteville committee, and together they marched directly to the Nation; a detachment from the main body proceeded to the house of a desperado, named whom they arrested and held, while others, with his wife for a guide, on Honey creek, where the execution took place. It was dead midnight. The ground had congealed. A full moon looked down from mid-heaven. The wind was still, the frosts glittered in the pale moonlight; nothing was heard, save the tramp of feet, or the distant hoot of the night owl. The main body of the committee were at the rendezvous, awaiting the arrival of the prisoners. The men were standing in groups or seated on fallen trees. All was still. No noise was heard- all seemed to be impressed with the solemnity of the occasion. With no light, save that of the full moon, the court was convened. The prisoner, Sanders, was brought forward, and walked with a firm step, taking a position directly fronting the judge, when the court addressed him as follows: "Richard Sanders, you are charged with one of the most infamous crimes known to the law-not one, but many. You are charged with murder, and, to make it still more infamous on your part and more horrible to a refined community, I will add assassination." Sanders interrupted the judge by saying: "It's a d-d lie!" The judge, without noticing the interruption, continued: "You are charged with stealing horses; you are charged with murder and robbery, in the broadest sense of the word; you are charged with being at the head of a band of murderers and marauders, who have, for years, made Johnson County the scene of death and destruction. And, to crown your long reign of infamy, I charge you with being the murderer of David Sweitzer." "It's a lie! Let it be proved," said the prisoner, in an altered voice, looking around him with a disturbed air. Sanders was livid. A legal arrest, perhaps, would have appeared less formidable. His audacity would not have forsaken him before an ordinary tribunal; but everything that now surrounded him surprised, alarmed him. He was in the power of those whom he had deeply wronged. The judge continued: "Yes, you have again spilled blood without any just provocation. The man whom you assassinated last night came to you in confidence, not suspecting your murderous intent. He asked you what you wanted. ' Your money and your life!' and you shot him dead." "Such was the story of Mrs. Groninger," said a man in the crowd. "It is false! She lied!" "Mrs. Groninger didn't lie," said the judge, coldly. "For the crimes you have committed you must die! If we turn you over to the civil authorities you will escape, or, by some of your comrades in infamy, prove an alibi, and be turned loose again upon society. No, it must not be. If, perchance, you were tried, found guilty and sentenced to death by a civil court, there would be a chance for you to escape justice, or you would stand on the scaffold if found guilty and jest with the hangman, or, I fear, profane the name of God with your dying breath. No, it must not be, you must die in secret; die tonight; die now. It will save your mother the shame of a son dying on the scaffold, and she can say, 'He was murdered, killed by a mob.' Listen! You are not the only one. Many of your companions will follow, and that soon! This last outrage is more than we can bear. Your crimes demand an extraordinary reparation. You have broken into houses with arms in your hands. You have shot men down in order to steal. You have committed another murder. You must die here. In compassion to your mother I will spare you the shame of the scaffold. I now sentence you to hang by the neck until dead!" Nothing could be heard but the quick breathing of the prisoner, or the whistling of the wind through the branches of the leafless trees. The voice of the judge was not harsh, but soft and sad. He was calm and collected, and every feature showed that he was about to accomplish a solemn and formidable mission. The prisoner was stupefied and seemed to be so overcome by the recollections of the past, that he uttered not a word. He was placed upon a horse, with a rope fastened from his neck to a limb above. The judge again asked, 'Who killed Sweitzer?' Sanders replied, 'I don't know. I think Morg Andrew.' Someone in the crowd cried, 'Oh! Hell, Dick; drive up the mule.' The horse was driven out from under, and the shadows of eternity gathered around him. The other prisoners were released without any confession on their part. The members of the committee then dispersed to their respective homes, with orders to be ready at a moment's warning, leaving the dead alone in the woods. "Vengeance to God alone belongs; but when they thought on all their wrongs, their blood was liquid flame." The chief of the outlaws was dead.

|

| In 1867 the Courthouse was here on Main Street, In Warrensburg, MO It is a museum today. |

WHEREAS; The greatest of crimes are becoming more and more frequent and punishment less and less certain; therefore, Resolved, That we, the people of the town of Warrensburg, and of the county of Johnson, without distinction of party, do pledge ourselves that we will, to the extent of our ability, assist in the discovery of the perpetrators of all murders and robberies, and will assist the officers of justice in detecting and punishing them; and as the civil law proves inadequate to bring such criminals to justice, therefore, Resolved, That we will support a vigilance committee, in executing summarily,' all murderers, robbers and horse thieves, wherever they can be identified with reasonable certainty, believing, as we do, that self-preservation is the first law of nature, and that the citizens of a county are justified in administering justice to such criminals, wherever the duly constituted authorities from any cause whatever, are unable or fail to do so.

Sanders was present during the meeting, but the instant it adjourned, disappeared. The committee organized, and by nine o'clock were on the march. "Hark! Peace! It was the owl that shrieked, the fatal bell-man, which gives the sternest good night," Night had again spread her black mantle over our half of the earth. The weather had moderated, the wind was soft and damp. The roads were soft and sloppy and disagreeable, it was nine o'clock. The Warrensburg committee consisted of about one hundred of our best citizens. They were joined at Fayetteville by the Fayetteville committee, and together they marched directly to the Nation; a detachment from the main body proceeded to the house of a desperado, named whom they arrested and held, while others, with his wife for a guide, on Honey creek, where the execution took place. It was dead midnight. The ground had congealed. A full moon looked down from mid-heaven. The wind was still, the frosts glittered in the pale moonlight; nothing was heard, save the tramp of feet, or the distant hoot of the night owl. The main body of the committee were at the rendezvous, awaiting the arrival of the prisoners. The men were standing in groups or seated on fallen trees. All was still. No noise was heard- all seemed to be impressed with the solemnity of the occasion. With no light, save that of the full moon, the court was convened. The prisoner, Sanders, was brought forward, and walked with a firm step, taking a position directly fronting the judge, when the court addressed him as follows: "Richard Sanders, you are charged with one of the most infamous crimes known to the law-not one, but many. You are charged with murder, and, to make it still more infamous on your part and more horrible to a refined community, I will add assassination." Sanders interrupted the judge by saying: "It's a d-d lie!" The judge, without noticing the interruption, continued: "You are charged with stealing horses; you are charged with murder and robbery, in the broadest sense of the word; you are charged with being at the head of a band of murderers and marauders, who have, for years, made Johnson County the scene of death and destruction. And, to crown your long reign of infamy, I charge you with being the murderer of David Sweitzer." "It's a lie! Let it be proved," said the prisoner, in an altered voice, looking around him with a disturbed air. Sanders was livid. A legal arrest, perhaps, would have appeared less formidable. His audacity would not have forsaken him before an ordinary tribunal; but everything that now surrounded him surprised, alarmed him. He was in the power of those whom he had deeply wronged. The judge continued: "Yes, you have again spilled blood without any just provocation. The man whom you assassinated last night came to you in confidence, not suspecting your murderous intent. He asked you what you wanted. ' Your money and your life!' and you shot him dead." "Such was the story of Mrs. Groninger," said a man in the crowd. "It is false! She lied!" "Mrs. Groninger didn't lie," said the judge, coldly. "For the crimes you have committed you must die! If we turn you over to the civil authorities you will escape, or, by some of your comrades in infamy, prove an alibi, and be turned loose again upon society. No, it must not be. If, perchance, you were tried, found guilty and sentenced to death by a civil court, there would be a chance for you to escape justice, or you would stand on the scaffold if found guilty and jest with the hangman, or, I fear, profane the name of God with your dying breath. No, it must not be, you must die in secret; die tonight; die now. It will save your mother the shame of a son dying on the scaffold, and she can say, 'He was murdered, killed by a mob.' Listen! You are not the only one. Many of your companions will follow, and that soon! This last outrage is more than we can bear. Your crimes demand an extraordinary reparation. You have broken into houses with arms in your hands. You have shot men down in order to steal. You have committed another murder. You must die here. In compassion to your mother I will spare you the shame of the scaffold. I now sentence you to hang by the neck until dead!" Nothing could be heard but the quick breathing of the prisoner, or the whistling of the wind through the branches of the leafless trees. The voice of the judge was not harsh, but soft and sad. He was calm and collected, and every feature showed that he was about to accomplish a solemn and formidable mission. The prisoner was stupefied and seemed to be so overcome by the recollections of the past, that he uttered not a word. He was placed upon a horse, with a rope fastened from his neck to a limb above. The judge again asked, 'Who killed Sweitzer?' Sanders replied, 'I don't know. I think Morg Andrew.' Someone in the crowd cried, 'Oh! Hell, Dick; drive up the mule.' The horse was driven out from under, and the shadows of eternity gathered around him. The other prisoners were released without any confession on their part. The members of the committee then dispersed to their respective homes, with orders to be ready at a moment's warning, leaving the dead alone in the woods. "Vengeance to God alone belongs; but when they thought on all their wrongs, their blood was liquid flame." The chief of the outlaws was dead.

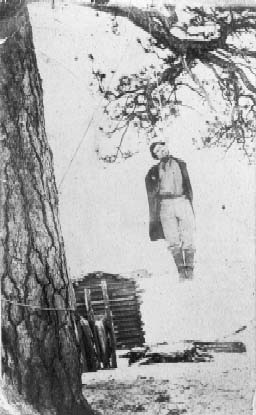

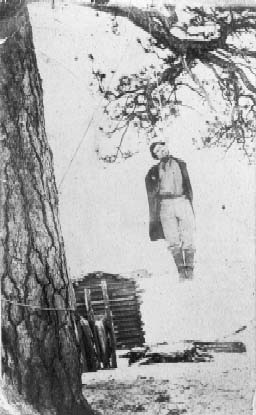

This Mob Hanging Was in Montana

They met the night after his death, February 28th, at the residence of "Bill Stephens," some five miles southeast of this city. It would be hard for one to describe the meeting, as information is not accurate; suffice it to say there were a lot of desperate looking men present. A stranger set of mortals one never set eyes upon. You would be puzzled to discover the least resemblance between them; each seemed to dress to suit his own peculiar taste, and carried a brace of revolvers belted around him. But we will not attempt to describe their costumes. And those heads! What a study for a white-coated phrenologist! It was the desperado band, and "Bill Stephens" was their chosen captain-their chief. Many of our readers knew him personally, but for those who were fortunate enough not to, we will attempt a description: Imagine a man six feet seven inches in height, lean and lank, weighing 175 pounds, sandy complexion, red hair and beard, pale blue eyes, nose resembling the beak of an owl, long bony hands, face marked with deep lines of dissipation, and you have a photo of "Bill Stephens." In future, he was to be their chief. They separated that night with the understanding that they would not attempt anything more until the storm blew over. It was the night of March 4th, a mixture of rain and snow had fallen the day previous; the clouds had blown away, and the night set in calm, cold and clear. It was three o'clock A. M. The waning moon was up and shed an uncertain light; the damp snow still clung to the branches of the trees, when a detachment of the committee, numbering about twenty men, started on foot, taking a southeast direction; each man was armed with a revolver and double-barreled shot-gun. Just before day they arrived at the residence of "Bill Stephens." It was the motto of the committee to kill those men without exposing their own lives in the act. They secreted them- selves in the barn, crib and along the fence, knowing that Stephens was a desperate character, and would not be likely to allow himself taken without a struggle. They abandoned the idea of hanging, and secreted themselves for the purpose of shooting him down as soon as he should make his appearance in the morning. For that purpose they waited. As the east began to flame with the fires of approaching day, and the blue canopy, so splendidly set with bright, sparkling gems began to fade to a dull grey, Stephens made his appearance at the door, in his shirt sleeves. Quiet reigned, broken only by the crowing of the early cock. A large dog met him at the door, the truest friend of man and Stephens speaking a kind word, stooped to stroke his fine canine head, when the report of twenty shot guns rang out on the still morning air, and Stephens fell, pierced by an unknown number of buckshot. He was taken in by some of the family, not dead, but in a dying condition. It was a terrible mode of obtaining the ends of justice, but there was no other alternative. It had to be. He lived until about 12 o'clock, when the last spark of life expired. Thus ended the career of Bill Stephens, the man who attempted to assassinate Gen. F. P. Blair, in this city, June 1, 1866, and who was the second chosen chief of the band. We may well say, that the master-stroke was given when Stephens fell. The crew dispersed, some to Kansas, Arkansas, Texas and different portions of Missouri, while a few of the most daring remained, among them, Jeff Collins. Pure was the cool air, and evening calm Perpetual reigned, save what the zephyrs bland, Breathed o'er the sombre expanse. The morning of March 4th, 1866, dawned calm, cool and clear. The news of Stephens' fate came to the city early in the morning, and was received with general satisfaction by the masses. One of the boldest and most dangerous of the clan was out of the way, and the band really broken up. The day turned out to be warm and pleasant; the snow melted away, leaving the ground again bare. There was an unusual stir on our streets during the middle of the day. The signs indicated that there was something up. It was soon discovered that it was the intention of the committee to arrest Jeff Collins, a notorious character, who had been making Warrensburg his headquarters for some time. Collins, in the forenoon was noticed to be filled with suspicion, and to remove that, it was necessary for the parties suspected to appear perfectly careless as to his whereabouts or movements during the day. Men whom he had held under a cocked navy with one hand, and slapped in the face with the other, met him on friendly terms, and drank with him often during the afternoon. The committee saw that his suspicions were aroused, and that he was making secret preparations to escape. As soon as this was ascertained, guards were thrown out in every direction, and men were stationed with glasses in the fourth story of Ming's hotel, to watch his movements. (Ming's Hotel was a four story building at 101 South Holden, it burned down in 1873 Link)

About four o'clock in the evening he went down Pine street to Washington Avenue, thence south to a house somewhere about Ming or South street, where he stopped. This was telegraphed from Ming's hotel by a given signal. Instantly fifteen or twenty men started in that direction with shotguns. They soon arrived, and secreted themselves behind fences and out-buildings; in this position they silently awaited his exit from the house. This building, the reader will recollect, stood on the hill south of the railroad. The last rays of the setting sun disappeared slowly behind the imposing mass of buildings that surround the public square. On every side, as far as the eye could reach, were spread out immense fields, whose brown furrows were hardened by the frost. A vast solitude of which the old square and its surroundings seemed the basis. The perfectly serene and cloudless sky was mottled in the west with long streams of purple a certain sign of wind and cold. These colors, at first very bright, became of a violet hue as the twilight advanced and the night came on. A young moon, like the half of a ring of silver, began to shine softly in the midst of the azure and shade. The silence was profound-the hour, we may say, solemn. At this moment Collins stepped out, intending, no doubt, to make good his escape in the gathering shades of evening, little thinking that the great orb of day had set for the last time between him and eternity. We will not attempt to describe the horror depicted in his countenance when, on raising his eyes they came in contact with twenty double barreled shotguns, cocked and levelled at his breast. In an instant he had taken in the situation. There was no escape. The commander of the squad said, "Jeff Collins, we want you. Surrender!" No man can say that Collins was a coward, for he was anything else; but at that moment he trembled, perhaps for the first time in his life. After a few moments' reflection, raising his trembling hands toward heaven, now becoming dull and gray by the shades of evening, he said, " I surrender. " The captain replied, "drop your pistols." Collins made a motion as though he was going to draw them from the scabbard, when the captain said, "stop, undo your belt, and drop them." Collins did as directed. The pistols dropped to the ground, and he stood there alone, friendless and defense- less. Night came on clear and cold. The committee had assembled in the large livery stable that stands in the rear of Ming's hotel. At that time the building belonged to other parties. It was nine o'clock. The judge was seated on a stool in the mouth of a stall, and the jury stood in a line across the front portion of the building. A side door was suddenly opened, and Collins appeared, pushed forward by several of the party, with his arms tightly bound behind him. He was no longer agitated; his handsome, dark face wore a scowl of hatred and defiance. There was no positive proof of his ever committing a murder; but circumstances were all against him, and the accusation of the judge was similar to that brought against Sanders, with the exception of the Sweitzer matter. Collins simply replied: "Well?" The judge then continued to accuse:

About four o'clock in the evening he went down Pine street to Washington Avenue, thence south to a house somewhere about Ming or South street, where he stopped. This was telegraphed from Ming's hotel by a given signal. Instantly fifteen or twenty men started in that direction with shotguns. They soon arrived, and secreted themselves behind fences and out-buildings; in this position they silently awaited his exit from the house. This building, the reader will recollect, stood on the hill south of the railroad. The last rays of the setting sun disappeared slowly behind the imposing mass of buildings that surround the public square. On every side, as far as the eye could reach, were spread out immense fields, whose brown furrows were hardened by the frost. A vast solitude of which the old square and its surroundings seemed the basis. The perfectly serene and cloudless sky was mottled in the west with long streams of purple a certain sign of wind and cold. These colors, at first very bright, became of a violet hue as the twilight advanced and the night came on. A young moon, like the half of a ring of silver, began to shine softly in the midst of the azure and shade. The silence was profound-the hour, we may say, solemn. At this moment Collins stepped out, intending, no doubt, to make good his escape in the gathering shades of evening, little thinking that the great orb of day had set for the last time between him and eternity. We will not attempt to describe the horror depicted in his countenance when, on raising his eyes they came in contact with twenty double barreled shotguns, cocked and levelled at his breast. In an instant he had taken in the situation. There was no escape. The commander of the squad said, "Jeff Collins, we want you. Surrender!" No man can say that Collins was a coward, for he was anything else; but at that moment he trembled, perhaps for the first time in his life. After a few moments' reflection, raising his trembling hands toward heaven, now becoming dull and gray by the shades of evening, he said, " I surrender. " The captain replied, "drop your pistols." Collins made a motion as though he was going to draw them from the scabbard, when the captain said, "stop, undo your belt, and drop them." Collins did as directed. The pistols dropped to the ground, and he stood there alone, friendless and defense- less. Night came on clear and cold. The committee had assembled in the large livery stable that stands in the rear of Ming's hotel. At that time the building belonged to other parties. It was nine o'clock. The judge was seated on a stool in the mouth of a stall, and the jury stood in a line across the front portion of the building. A side door was suddenly opened, and Collins appeared, pushed forward by several of the party, with his arms tightly bound behind him. He was no longer agitated; his handsome, dark face wore a scowl of hatred and defiance. There was no positive proof of his ever committing a murder; but circumstances were all against him, and the accusation of the judge was similar to that brought against Sanders, with the exception of the Sweitzer matter. Collins simply replied: "Well?" The judge then continued to accuse:

"You are charged with being a member of the band of robbers that have for so long infested this country." "Well?" The judge continued, "What have you to say in defense of these charges?" "Nothing." Judge, "Are you guilty as charged?" "You are the judge, not I." Judge. "Then you have no defense to make?" "No; it would be of no use. Your court sits to convict, not to try." Judge!" Confess your crimes and it may not go hard with you." "I confess nothing." The judge then addressed the jury: "Gentlemen, what shall be done with the prisoner?" The jury replied, unanimously, "Hang him." The court then proceeded to sentence: "Jeff Collins, I sentence you to be hung by the neck until dead! dead!! dead!!!" Instantly a door on the east side of the building flew open, and the crowd started, leading the prisoner with ropes. It is needless to say that the jury had decided the fate of Collins before he was brought before them. The party passed out East Culton Street to McGuire, thence south along the railroad bridge, and stopped under the spreading branches of an old black-jack tree, where the execution took place.

A rope was adjusted around his neck, thence over a limb above. Judge, "Have you any word to leave?" "Yes. Tell my mother that I died a brave, but innocent boy." At that moment several men fell back on the rope, and Collins was drawn from the earth, to descend no more alive. The body was allowed to hang that night and the next day, but disappeared the next night. It is supposed that his body was dissected by the medical fraternity of this city, and that the skeleton was consumed in the great fire of 1867. The train bell tapped. Hear it not Stephens, Andrews? "For it’s a bell that summons thee to Heaven or to hell."

|

| Jeff Collins Vigilante Hanging Was Here. Possibly from one of these Blackjack Trees on Maguire at Grover. Foster School Pictured Here, Warrensburg, MO |

The next two individuals heard from were Thomas Stephens, son of Bill Stephens, and Morg. Andrews. The authorities of Johnson county being informed that they were in the jail at Lawrence, Kansas, sent for them. They were delivered to the officers according to law, a requisition having first been served upon the governor of Kansas by the governor of Missouri. The prisoners were both young, neither of them being over eighteen or nineteen years of age. Stephens was tall, dark, black hair and eyes. Andrews vice versa.

"It was an evening bright and still as ever blushed on rose or bower, smiling from Heaven, as if naught of ill could happen in so sweet an hour." It was eleven o'clock; the night was calm and clear; the gentle breeze floated from the south; the dew-drops clung tenderly to the shrubs and trees; the flowers filled the air with fragrance, and the night-birds piped their plaintive songs from the spreading boughs of our giant oaks; the moon, the waning moon, shed a dim shadow-light, making every object appear ghastly and uncertain. This night two more souls were sent to eternity. At last the loud, shrill whistle of the down express was heard. The committee were in waiting, and divided into detachments. The train stopped, and the prisoners were taken off by the civil officers in charge, who attempted to take them to the county jail, by smuggling them out at the rear of the train, but the vigilantes were in the rear, as well as the front.

They had proceeded but a short distance when they were met by a party of some fifty armed men who relieved them of their charge. The officers made but feeble resistance and were soon overpowered. The party then bound their hands behind them, with instructions to leave and keep quiet, which they did without much grumbling. Then came the procession through town to the place of execution. They were led along the shadowy street, No look of kindness, all was frown; so they hurried through the pitiless town. On they passed, door after door, "The happy homes of rich and poor;" Trembling and fear of the pitiless mass, they arrived at the old public square at last. There they were met by at least four hundred men, who were signaled to that point by a skyrocket, the most of them being members of the Fayetteville committee. The procession was formed on the north and east sides of the square. The prisoners were placed in a hack, and the procession moved slowly in the direction of Post Oak bridge. There was no excitement. No boisterous demonstrations were indulged in, and we may say it was a solemn procession, sad, yet pitiless. Soon the sound of the advance was heard crossing the bridge. The loud, keen whistle of the Eureka Mills broke the dead stillness of the night, and we knew that it was 12 o'clock and that the night was waning.

|

| Eureka Mills, Built by Land, Fike and Company Warrensburg, Missouri |

The declining moon shed a silvery, silken veil of light that struggled through the gentle swaying branches of those aged elms, that had so long stood as landmarks west of the bridge, and gently "kissed the upturned faces of a thousand roses," that grow where the wind hardly dare stir, unless on tiptoe, filling the cool, mid-their graves again." It was a sad sight to see those young men about to be cut off in the bloom of youth-to see them leave this bright, beautiful, joyous world of ours, where their lives had been so long shadowed with crime, caused from evil counsel, but they had no other advisers. The counsels of a mother had been denied them, and they were now to undergo the suffering that comes only with crime. Without even a prayer in the last moments of their existence, the hack that contained the prisoners was backed up under the suspending ropes, and they were commanded to look upon their doom. Stephens, with an unflinching eye, gazed upon his gallows, while Andrews begged for mercy and his life. Mercy! Mercy! There was none for them. A large heavy man stepped from the crowd and preferred charges against them. He said: "You were with the party that killed and robbed Sweitzer; your comrades are disappearing one by one. You go tonight; your last hour has come. Prepare for death! If you have a prayer to offer to your God, pray." Stephens stood erect with his head thrown back, showing a nerve that nothing but death could destroy. He spoke in a firm but boyish voice and said: "I have never, in all my life, spilled a drop of human blood. The charge of my killing Sweitzer is false! I know you are going to kill me, and there is no use of my wasting your time in talking." Then quietly drawing a small portmonie (wallet) from his pocket containing a few pieces of money and a trinket or two, asked: "Is there one man in this vast crowd who will do me the kindness to deliver this to my young sister. It is small, but all I have." A man stepped forward and took the souvenir and promised to fulfill the trust. "Tell her," said Stephens, "to accept this from her brother who dies an innocent boy. You will find her in the city." The rope was then adjusted around his neck and the driver ordered to move forward; but Stephens anticipating this, sprang from where he stood, and hung a lifeless corpse. Andrews was then made to look upon his dead comrade and was told to pray. He said, while tears rolled down his face, "I cannot pray, in all my life I have never been taught a prayer." He then asked: "for God's sake, somebody pray for me; don't send my soul to hell. Will no one pray? Oh! God! I little thought this world was so hard-dying without a prayer. It is awful, out of all this great crowd, not one will bow down and ask God to forgive me while I die." Someone in the crowd yelled out, "we are like you, we can't pray." He knelt down and tried to pray to the Giver of all good for that mercy that was denied him on this earth. The only words audible were: "Oh God, have mercy on me and save my soul." Oh, the agony of that hour was terrible to that poor brutal boy. Then the command was given to "swing him off." The hack moved from under his clutching feet, and he hung, a wretched, quivering mass. A dark-gray, fleecy cloud came drifting along through the beautiful vaulted heavens and drew for a moment its shadows over the face of the moon. The breeze that was gently wafted through those old branches, moved the dead to and fro. Men moved toward their homes, leaving the dead alone. The wind and the waters chanted their requiems around the unfortunate pair. It was finished. "They have gone beyond Even their exorbitance of power; and when this happens in the most condemned and abject Communities, stung humanity will rise to check it." After the execution of Stephens and Andrews, some of the medical men of our city took possession of their heads. The bodies of the unfortunate boys were buried on the banks of Post Oak, near the place of execution early next morning.

As an incident of that night, a wedding party coming home from the country after three o'clock, drove between the dead men, the driver thinking they were two men standing in the road. The horses struck them with their heads, swinging the bodies to and fro. The driver stopped his team just in time for the dead men to swing their ghastly faces in the door on each side of the carriage. It is needless to say that two ladies fainted, and their escorts have never been known to be out after night since. A man by the name of Hall, was hung by the Fayetteville committee some time about the last of March. The only true statement of facts connected with this execution is, that a man was arrested, confessed killing several men, and was accordingly hung.

As an incident of that night, a wedding party coming home from the country after three o'clock, drove between the dead men, the driver thinking they were two men standing in the road. The horses struck them with their heads, swinging the bodies to and fro. The driver stopped his team just in time for the dead men to swing their ghastly faces in the door on each side of the carriage. It is needless to say that two ladies fainted, and their escorts have never been known to be out after night since. A man by the name of Hall, was hung by the Fayetteville committee some time about the last of March. The only true statement of facts connected with this execution is, that a man was arrested, confessed killing several men, and was accordingly hung.

The next case in which the vigilantes took any part, was that of Thos. W. Little, who was arrested with another man named Myers, and brought to Warrensburg. The charges against Little were very insignificant, and about as follows: Some man was knocked down and robbed of a few dollars, west of Post Oak bridge. Little was charged with the offense, and was tried for it; but the committee failed to convict, from the fact that there was no evidence to substantiate the charge, and the prisoner was sentenced to jail. A few nights afterwards another trial was held in the old billiard hall west of the square, in West End. Several prominent men from Dover were there for the purpose of proving an alibi, among them Dr. Ming. The statement of all these gentlemen went to prove that Little, at the time of the alleged robbery, was in Dover. It was put to a vote whether the committee should hang him or not. The vote stood about as follows: For acquittal, 344; for convicting, 28. From that count it will be seen that the committee were in favor, as a majority of letting the accused one go free. By their vote they pronounced him "not guilty, as charged." After these proceedings the Committee dispersed. But the strangest feature of this case was the fact, that some ten or twelve of our most prominent citizens, after waiting so long, joined the committee that very night and urged with enthusiastic appeals, the necessity of killing Tom Little. "No voice of friendly salutation cheered him; none wished for him to live, or bade God spare him; But through a staring, ghastly-looking crowd, Unhailed, unblessed, with heavy heart he was dragged." It was a warm, sultry, moonlight night in August. About 3 o'clock, a.m., some fifteen or twenty men gathered at the county jail and demanded Little. The jailer without any resistance stood by and saw the jail door battered down, and the prisoner dragged out. He was taken down Main street to a small elm tree, where he was hung.

Not by the vigilance committee or by their order, but by men who live in Warrensburg, and who never had any connection with the committee until the night of the disgraceful murder of Thomas W. Little, and who very probably joined for the purpose of using their influence in hanging him, and failing to carry the vote, they concluded to hang him on their own responsibility, and against the wishes of a majority of the committee. Having no old grudge against Myers, these new members of the committee did not see proper to murder him. The hanging of Little wound up the career of the vigilance committee in Johnson County, as an organization. Strife and contentions arose in the organization. Leaders were arrayed against one another. The murder of Little was condemned by the masses, as an outrage. Might had triumphed over right. The committee now assumed the costume of night itself, and became powerful and dangerous. It was no longer a terror to the Sanders and Stephens’s gang, for they were dead or scattered to the four winds of heaven, but, became a terror to themselves and to the community at large. It was no longer an organized body, but a blind, passionate mob, threatening to destroy the lives and property of our oldest and best citizens, and were only deterred from executing their threats by the grim muzzle of shot-guns and revolvers. The Journal office, then a democratic paper, was guarded to prevent them destroying the presses and type, simply because it had published an article telling the committee that they had gone far enough, and asking them to disband.

All executions, after the hanging of young Stephens and Andrews, were without the consent of the committee and against their wishes.

|

| Hangings In Warrensburg, Mo. Would Have Been Similar to This One in Montana in the 1860s |

All executions, after the hanging of young Stephens and Andrews, were without the consent of the committee and against their wishes.

The next victim of these men was one James M. Sims, a half crazy fellow who was charged with stealing a horse. The facts are about as follows: In the month of September, a boy went to Post Oak Bridge for the purpose of watering a horse. As he returned to town he was met by Sims, who asked what he would take for the horse. The boy replied that the horse was not for sale. Sims then asked if the horse could pace; the boy answered that he could. Sims then asked permission to try him; the boy dismounted and Sims got on the horse and galloped off. He was followed and captured southeast of Clinton, on Grand River. The parties having him in charge, returned to Warrensburg the next day. Before they reached town they were met and told that they had better change their course, as there were men waiting in town for them to arrive, with the intention of taking the prisoner from them. They made a circuit coming in near Smith's mill, West End, where they were met by some fifty armed men, who demanded the prisoner. He was no sooner demanded than given up; the party then proceeded to the creek where the execution took place. They informed the prisoner that they were going to kill him. He told them that he couldn't help it, and asked for paper and pencil; they were given him when he wrote the following note on the horn of his saddle:

"WARRENSBURG, September 1867. Dear Mollie: As I write, I am only waiting to face death. I am now going to die, and as you know, I die for your sake, and my soul shall cling to yours, whether to heaven or hell it goes. Goodbye. J. M. SIMS."

After writing this note, he climbed up in a wagon that stood under the tree, remarking, that he would rather be on top of the limb than under it.

"WARRENSBURG, September 1867. Dear Mollie: As I write, I am only waiting to face death. I am now going to die, and as you know, I die for your sake, and my soul shall cling to yours, whether to heaven or hell it goes. Goodbye. J. M. SIMS."

After writing this note, he climbed up in a wagon that stood under the tree, remarking, that he would rather be on top of the limb than under it.

The rope was placed around his neck, and the wagon driven out from under Sims, the ninth victim of that Reign of Terror.

As a sequel to a paragraph of the foregoing sketch we submit the following entry from a diary made at the time: "JONES CREEK, January 22, 1879. It has been a miserably disagreeable day. Snow, rain and sleet following alternately, with a strong northeast wind. The country passed through today is very sparingly settled, and I have had trouble to find lodging. The old settlers here show but little hospitality, and that much bested 'christian charity' is more liable to be found in poetry and songs, than in reality. My efforts were at last rewarded by being permitted to stopover night, provided I could 'put up with the fare.' This I eagerly consented to do, for I was tired, cold and hungry. Upon entering the old fashioned Missouri double log house, I found a splendid fire burning in the huge old fire place, and a warm supper on the table, awaiting the attack. During the evening I learned that the name of 'mine host' was William Collins, known here as 'Uncle Billey,' and that he was the father of Jeff. When they learned where I was from, the old lady became very much excited, and very abusive. The family consists of the old gentleman and lady and one daughter at home. The young lady is a decided brunette, and very pretty featured. At the time of the execution of Jeff, she was about thirteen years old, and the shock occasioned by the news of the death of her favorite brother was too much for her, and threw her into a long spell of brain fever. Upon recovering her physical strength, it was found that her mental faculties were gone, and she has been hopelessly insane from that time to this. The gravest charge against Jeff Collins; was the murder of one John Barbee, an ex-bushwhacker near Granby. I learned from parties who were conversant with the facts in the case, that Barbee was not killed by Collins. The facts in the case are as follows: Collins and Barbee met at a saloon in Granby, where they had some altercation over some differences. The affair was supposed to have been amicably settled between them, and Collins started home on a neighbor's wagon, and was overtaken by Barbee on horseback, who lived in same neighborhood, when the trouble was renewed. Collins told Barbee that they would settle the affair then and there; at the same time leaping from the wagon, drawing his revolver and firing. Barbee jumped from his horse and took to the woods with a pistol ball through his hand. This is the only case that has come under my immediate observation since those premature executions, and I have made up my mind that if the charges preferred against the rest of those unfortunate victims, were as recklessly made, and the proof as malicious as in the case of Jeff Collins, that it would have been far better to have left it undone."

History of Johnson County Missouri 1881