Link to Rural Missouri Story on Lt. Whiteman 2015 |

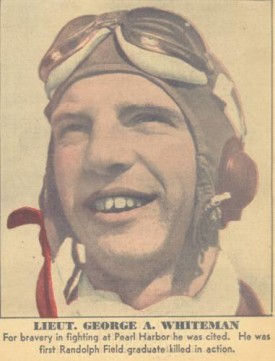

| Lt. George Allison Whiteman, Sedalia, sits in the cockpit of his training school aircraft. The photo is taken from a postcard Lt. Whiteman sent his sister upon graduation in 1940. The words "Lucky, Lucky Me" were his description of how he felt at the moment. |

Born Oct. 12, 1919, Sedalia, Missouri

KIA December 7, 1941

Bellows Field, Hawaii Age 22 (Pearl Harbor Attack)

Namesake of Whiteman Air Force Base - Home of the B-2

Namesake of Whiteman Air Force Base - Home of the B-2

"Upon arriving and seeing that the destruction had left no planes in flying condition (at Wheeler field), Whiteman raced to Bellows Field. Cpl. Harold Kolom, sitting under the wing of a plane writing a letter, looked up to see nine Zeros attacking an incoming B-17. As Corporal Kolom ran towards a parked plane, he saw Lieutenant Whiteman's car race up to the runway.

Maj. D.L. Waddington also saw Lieutenant Whiteman run to one of the P-40s where men were loading ammunition into the guns. Lieutenant Whiteman started the engine and taxied out to the runway with the engine still cold. In fact, Whiteman had been so quick to leave that the armorers did not have time to install the gun cowlings back on the wings. The young aviator began his take-off and had gotten approximately 50 feet in the air when two Zeros opened fire on him. He attempted to turn inside the two Zeros on his tail; however, the P-40 was too slow and cumbersome. Enemy bullets hit the engine, wings, and cockpit. Lieutenant Whiteman tried to make a belly landing on the beach north of the field but instead crashed and the plane went up in flames.

|

| Bellows Field, Hawaii Crash site of Lt. George Whiteman, Whiteman Air Force Base Namesake |

The news of Lieutenant Whiteman's death reached his family at 10:13 p.m. on the evening of Dec. 7, 1941. The telegram read: "Second Lt. George A. Whiteman killed in action this date. Further information will reach you from War Department Washington. Sincere sympathy, Short, Commanding General, Ft Schafter."

|

| Lt. George A. Whiteman's temporary gravesite Bellows Field Dec. 1941, Hawaii Whiteman Air Force Base Namesake, George Williams Photo, nephew |

|

| Lt. George A. Whiteman, killed in action December 7, 1941 Bellows Field, Hawaii, Telegram December 8, 1941 to his family in Sedalia,MO Photo George Williams, Nephew.  |

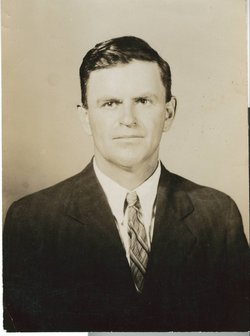

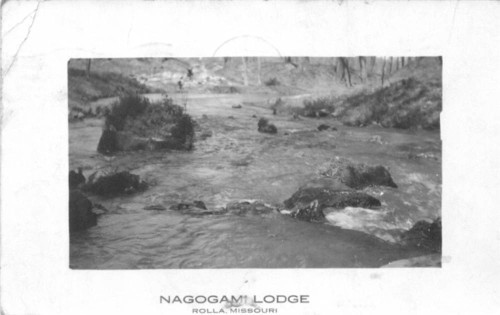

George Allison Whiteman, the eldest of 10 children of John and Earlie Whiteman, was born on Oct. 12, 1919, at the Wilkerson farm near Longwood, in Pettis County, Mo. He graduated from Smith-Cotton High School in Sedalia and attended the Rolla School of Mines, Mo. before enlisting in the service in 1939.

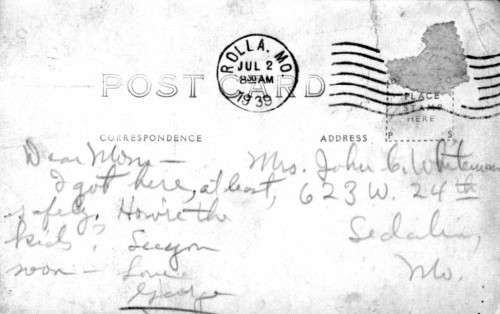

In the spring of 1940, Whiteman received orders to report to Randolph Field, Texas, for training as an aviator. On Nov. 15, 1940, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army Air Corps and volunteered for duty in Hawaii early the following year.

As the sun rose over Oahu on the morning of Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor began. Lieutenant Whiteman went to his P-40B Warhawk aircraft at Bellows Field and had just lifted off the runway when a burst of enemy gunfire hit his cockpit, wounding him and throwing the plane out of control. The plane crashed and burned just off the end of the runway. Lieutenant Whiteman died from his injuries.

The news of Lieutenant Whiteman's death reached his family at 10:13 p.m. the same day. In an interview with the Sedalia Democrat that night, his mother said: "It's hard to believe. It might have happened anytime, anywhere. We've got to sacrifice loved ones if we want to win this war." She gave the reporter a photograph of her son sitting in an aircraft with the inscription "Lucky, lucky me."

Whiteman was one of the first Airmen killed during the assault which marked the United States entry into World War II. For his gallantry that day, Lieutenant Whiteman was posthumously awarded the Silver Star, the Purple Heart, the American Defense Medal with a Foreign Service clasp, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign medal with one bronze star, and the World War II Victory Medal.

Another honor bestowed on Lieutenant Whiteman came 14 years after his death. On Aug. 24, 1955, Gen. Nathan F. Twining, Air Force chief of staff, informed Whiteman's mother that the recently reopened Sedalia Air Force Base would be renamed Whiteman Air Force Base in tribute to her son. The dedication and renaming ceremony took place on Dec. 3, 1955.

Source: Whiteman Air Force Base, Mo., Office of History

Citation: The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the Silver Star Medal (Posthumously) to George A. Whiteman, 2nd Lieutenant (Air Corps), U.S. Army Air Force, for gallantry in action while serving as a Pilot of the 44th Pursuit Squadron, 18th Pursuit Group, at Bellows Field, Island of Oahu, territory of Hawaii, on 7 December 1941. When surprised by a heavy air attack by Japanese Forces on Bellows Field and vicinity and while under fire, Second Lieutenant Whiteman attempted to take off to engage the enemy, and while so doing was shot down in flames by enemy aircraft.

Whiteman was one of the first Airmen killed during the assault which marked the United States entry into World War II. For his gallantry that day, Lieutenant Whiteman was posthumously awarded the Silver Star, the Purple Heart, the American Defense Medal with a Foreign Service clasp, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign medal with one bronze star, and the World War II Victory Medal.

|

| Bellows Field, Hawaii |

|

| P-40 at Bellows Field, Hawii |

|

| P-40, similar to the plane 2LT George Whiteman Flew on Dec 7, 1941 |

Bellows Field

Name: George Allison Whiteman

Rank: Lieutenant

Service Branch: Army

Date of Birth: October 12, 1919

Date of Death: December 7, 1941

George enlisted in the army on October 20, 1939. He was assigned to the Eighteenth Pursuit Group, Forty-Fourth Pursuit Squadron at Wheeler Field on Oahu. On December 7, 1941 George was killed in the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. When he went up in his plane, he was spotted immediately by two Japanese fighters. At least two, if not three, enemy planes opened fire on him. He was hit by enemy fire and attempted to make a belly-landing. His plane crashed and burned. George died in the fire.

On October 1, 1955, the name of the Sedalia Air Force Base in Knob Noster, Missouri, was changed to Whiteman Air Force Base, and on December 3, a dedication ceremony was held. Two weeks later, on December 17, a special group of dignitaries was invited to a "briefing and orientation" at the base.

|

| Whiteman, George Allison, 2LT | ||

Last Rank Second Lieutenant

Last Service Branch Aviation

Last Primary MOS AAF MOS 1056-Pilot, Single-Engine Fighter

Last MOS Group Aviation (Officer)

Last Unit

1940-1941, AAF MOS 1056, Hawaiian Command

Service Years

1939 - 1941

| Personal Details | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Ribbon Bar

| |||

| |||

Unit Assignments

| |||

| |||

Last Known Activity George Allison Whiteman, the eldest of ten children of John and Earlie Whiteman, was born Oct. 12, 1919, at the Wilkerson farm near Longwood, Mo., in Pettis County. He graduated from Smith-Cotton High School in Sedalia and attended the Rolla School of Mines in Rolla, Mo., prior to enlisting in the service in 1939.

In the spring of 1940, Whiteman received orders to report to Randolph Field, Texas, for training as an aviator. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army Air Corps Nov. 15, 1940, and volunteered for duty in Hawaii early the following year.

As the sun rose over Oahu on the morning of Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor began. Lieutenant Whiteman got to his P-40B aircraft at Bellows Field and had just lifted off the runway when a burst of enemy gunfire hit his cockpit, wounding him and throwing the plane out of control. The plane crashed and burned just off the end of the runway.

The news of Lieutenant Whiteman's death reached his family at 10:13 p.m. Dec. 7. In an interview with the Sedalia Democrat that evening, his mother, Earlie Whiteman, said: "It's hard to believe. It might have happened anytime, anywhere. We've got to sacrifice loved ones if we want to win this war." She gave the reporter a photograph of her son sitting in an aircraft with the inscription "Lucky, lucky me."

Lieutenant Whiteman is believed to be one of the first Airmen killed during the assault which marked the United States' entry into World War II. For his gallantry that day, he was posthumously awarded the Silver Star, the Purple Heart, the American Defense Medal with a Foreign Service clasp, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign medal with one bronze star, and the World War II Victory Medal.

Another honor was bestowed on Lieutenant Whiteman 14 years after his death. Gen. Nathan F. Twining, Air Force Chief of Staff, informed Mrs. Whiteman on Aug. 24, 1955, that the recently reopened Sedalia Air Force Base would be renamed Whiteman Air Force Base in tribute to her son. The dedication and renaming ceremony took place on Dec. 3, 1955

Comments/Citation George Allison Whiteman was born on the Wilkerson farm near Longwood, Missouri in Pettis County on October 12, 1919. His parents were John Casey and Earlie Sanders Whiteman. John was an oil truck driver. John and Earlie had ten children which included eight boys and two girls. George, named after Mr. Whiteman's father, brother, and George Wilkerson, was the oldest child. The other children born to John and Earlie were Paul, John Jr., Eugene, Carl, Marshall, Robert, Lee, Violet and Susan.

Until George started school, he lived with his family on the Wilkerson farm. Throughout his early years, he had a strong interest in World War I and especially in airplanes. He often expressed his desire to become a pilot. After his family moved to Sedalia, George attended Horace Mann Elementary School and Jefferson Elementary School, then later Martha Letts Junior High School. In 1926 at the age of seven, George's I.Q. was determined to be 128. George used his academic abilities to complete a curriculum in six years that was designed to take eight years. On September 8, 1931, at the beginning of his ninth grade year, he entered Smith-Cotton High School. While at Smith-Cotton, he continued a rigorous academic schedule by taking courses in English (four years), Civics, Algebra I, Plane Geometry I, Solid Geometry, Advanced Arithmetic, Advanced Algebra, Manual Training (two years), Bookkeeping I, Typing I, American History, American Problems, Chemistry I, Physics I, and Physical Education (four years). His favorite subject in school was chemistry. George also developed an insatiable appetite for reading. One of his favorite magazines was "Popular Mechanics." During his school years, his habit of reading earned him much teasing from his brothers, sisters, and friends. In fact, he could usually be found reading a book on the one-and-a-half-mile walk to and from school. On several occasions, he was so engrossed in his reading that he was almost hit by a passing car. On May 23, 1935, at the age of 15, George graduated from Smith-Cotton with a rank of 22 out of a class of 218 students. While George was at Smith-Cotton, the family's address was listed as Walnut and Heard Streets.

Though the country was embroiled in the midst of the Great Depression when money was scarce, George wanted to go to college. His father was unable to provide any financial help toward his education, but George was not to be deterred. He chose to enter Rolla School of Mines in Rolla, Missouri in an attempt to get a degree in Chemical Engineering. He received a scholarship and, during his first two semesters at Rolla, he took courses in General Chemistry, General Engineering Drawing, Philosophy and Composition, Algebra, Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), Physical Education, Qualitative Analysis, Geometry, Trigonometry, and Analytical Geometry, and also attended a special lecture. In an attempt to support himself and ease his financial burdens, he accepted odd jobs and stoked furnaces. He roomed with an elderly lady in Rolla and some of his earnings went toward his room. He accepted a fifty dollar loan for tuition from his high school Trigonometry teacher, Mattie Montgomery or "Mathematical Mattie" as she was known to her students. By participating in ROTC, George was also able to receive a few more dollars. His sister, Violet, recalled that he hitchhiked home on the weekends to be with his family. She also remembers her father taking him to the edge of Sedalia and sometimes, if he was unable to get a ride, his father would drive him to Rolla. Whiteman was proud to be a freshman at Rolla. In fact, he thought the Rolla School of Mines was second in academic excellence only to The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Whiteman took exceptional pride in the green beanies that freshmen were required to wear. Although this would bring him much hazing, he didn't mind. On many occasions, he could be heard singing the Rolla engineer song which went: "I am a rambling wreck from Rolla Tech, and a hell of an engineer." After George's death at Pearl Harbor, one of his college professors wrote the family to say that Whiteman had, during an oral discussion, come up with a theory that would later be known as radar. Due to financial hardship, George was forced to discontinue his college education after his second year at Rolla.

George moved to Chicago, Illinois in 1937. There he took a job with White Castle cooking hamburgers. He was provided two meals a day in addition to the money he earned. His average salary during this time was $18 a week. His youngest sister, Sue, took a job as a stenographer and was earning $5 a week. At Christmas time, Sue sent money to George in Chicago and, combining her money with his money, he bought presents for the family from both of them. Violet remembered the excitement and joy the large box brought to the family as it sat in the dining-living room. For his brothers, Marshall, Carl, and Bobby, he had bought shirts and corduroy overalls. Sue recalled he had used good taste when picking the gifts. Marshall received everything in blue to go with his eyes and platinum hair color. Carl and Bobby received dark colors to match their hair and eyes. Each child had received a toy and, of course, there was a present for his mother. Sue also received a gift of sheer hosiery, although she and George had made a prior agreement not to spend anything on each other.

George had a girlfriend, Marian, and, many times, he didn't have enough money to take her out. Consequently, they visited museums, went for walks, and had Coca Cola dates. He advised his sister, Violet, that you didn't have to spend a lot of money in order to have a good time. During this time, his sister, Sue, married Ray Berry and moved to Chicago for six months. She remembers the good times the three of them had visiting the Marshall Field Museum and that she would cook special meals for Ray, George, and herself on her days off. One story she recalls is about George's girlfriend, Marian. Marian was the sister of a college friend of George's. She worked as a governess for a well-to-do family. One evening, the family threw a dinner party and the butler failed to show. George immediately volunteered to take his place and apparently had a good time. Sue accredits his successful performance for the evening to all the Sherlock Holmes and other English books he had read. In fact, at one point, Sue found 32 thick books from the local library while cleaning his apartment. After George was killed at Pearl Harbor, the hostess of the dinner party, Mrs. Porter, wrote Sue a very nice letter concerning George Whiteman.

Shortly after Sue and her husband returned to Missouri, George followed. It was at this time that he joined the Coast Artillery. His serial number was 6 934 535. He was now able to repay his loan to Mattie Montgomery who had helped him attend Rolla. Determining that George was underweight, the recruiters suggested he join the Army, gain some weight, and then try for pilot school. On October 20, 1939, after some consideration and still possessing a desire to become a pilot, George Allison Whiteman enlisted in the United States Army. His serial number was 0 399 683. In one of his letters, George describes one of his first experiences in the Army. His first duty station was in Leavenworth, Kansas. When he departed Leavenworth by train for Fort Winfield Scott, California, he apparently slept through Kansas but did see most of Colorado. In Denver, his outfit switched trains from the Union Pacific to the Denver, Rio Grande, and Western rail lines. In his letter, Whiteman was so enthralled by the scenery he was seeing in Colorado, he found it difficult to express its beauty in writing. He fell asleep in Western Colorado and, when he awoke, he was greeted by the sight of the Great Salt Lake in Utah. He claimed ". . . if it hadn't been for the haze, I believe you could have seen for 20 miles in the flat." On the third day, they arrived at their destination, Fort Scott. His impression of California was that the state was "too foggy. . . and the air isn't fresh." It was on this trip that his unit got introduced to mess kits. It seems that eating with them on the train was an amusing experience, but he didn't go into the details in his letter.

His sister, Violet, had received a letter from him saying that he would visit her in Denver, but when the date came and went without his arrival, she began to wonder what had happened. Shortly thereafter, she received another letter saying, "Vi, I won't be there, in a fit of peeve I joined the Army." She never found out what the peeve was.

His letters from California center mainly on financial concerns. A letter dated December 21, 1939, talks of insurance and his promotion from Buck Private to Private First Class, increasing his monthly wages from $21 to $30 a month. It is also here that he mentioned for the first time to his battery commander about an assignment to Randolph Field, Texas. It was at Randolph that the army trained its pilots, and George was going to be able to attain something he had dreamed about all his life. He had confidence that he could also go to West Point, but his preference was flying. His letter also relates the fact that he was now considered a soldier instead of a recruit and this meant passes into town. He closed with rumors of the unit moving "everywhere - from Alaska to Panama" and the desolation of living in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) barracks that were their home on the base.

On February 2, 1940, his sister, Sue, received another letter. In it, he apologized for not writing sooner. He had been participating in maneuvers and had been unable to write. He wrote of his ex-girlfriend, Marian. He was puzzled about the name she chose for her child. "It doesn't sound like Marian," he wrote. This letter closed with a story about the photo he enclosed. Whiteman wrote that he had grown a mustache just to prove he could and then shaved it off.

In the spring of 1940, George finally reported to Randolph Field, Texas to be trained as an army aviator. Once there, he described his schedule as "ground school, flying planes, drill, athletics, studying, 10:00 p.m. bed check, and 6:00 a.m. reveille." He wrote that the "washout" rate in the first six weeks of training was 40%. "Washout" referred to those who failed and were then reassigned to other training programs. He said if he were to get "washed out" of flying training, he would take a discharge and go to New Mexico seeking work as he had a few prospects in that state.

A letter dated April 6, 1940, spoke of his concern for his sister, Violet. He was worried over the fact that she had fallen in love with a sick soldier. His feeling on the subject, however, was that it was none of his business. He mentioned another girlfriend, Grace, who was a fashion model and he wrote that, if he had a family, perhaps he would have something to do in the evenings. This letter states he had flown ten hours since arriving at Randolph.

In a letter dated April 24, 1940, he wrote his sister, Sue, that he hadn't heard from the model in two weeks. He also mentioned that he had received another letter from Violet, gave compliments to Sue's husband, Ray, on his ambition to fly, talked of a cross-country flight in PT RYAN trainers, night flying training, his hope to graduate flying school in November, a desire that "Hitler'd fall out of bed and break his neck," and closes with a wish for some news from home as he had not heard from them in awhile.

In an undated letter from Lindbergh Field, San Diego, he talks about arriving in San Antonio, Texas on July 1st, 1940. He asked about his father and if he still worked at the Missouri State Fairgrounds. He also mentioned some pay matters and, more importantly, he stated that he had 35 hours of flying time with 15 of that being solo. ". . . I feel important!," he wrote. He closes the letter asking about Marian and her brother, Howard.

On August 16, 1940, The Sedalia Democrat ran an article that George was to take examinations for commissioning later that week. It also said that George had transferred from Fort Baker, California to the Aviation Division and Ryan Flying School at Lindbergh Field, then on to Randolph Field, Texas.

On November 15, 1940, George A. Whiteman was honorably discharged from the Army and accepted his commission as a Second Lieutenant in the Army Air Corps Reserve. He had served seven months and 19 days from his time of enlistment until graduating as a pilot. His discharge papers described the young aviator as having gray eyes, light brown hair, fair complexion, and five feet nine-and-a-half inches tall. He wrote his mother and father that he and 16 other men had volunteered for duty at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. He mentions that he would fly one of the army's best fighters, the Curtiss P-36 Hawk, to San Diego, California where they would be put on an aircraft carrier, the USS ENTERPRISE. He would then be a passenger on the carrier and, once arriving in Hawaii, would fly the plane to the base there. In this letter, he also informs the family that he would no longer be permitted to explain in detail what he was doing. Security within the military was getting tighter.

A letter to Sue, dated February 7, 1941, says about the same thing. He alludes to the fact that he believes he made a wise choice in going to Hawaii. He knew he would have to do some overseas duty and thought it better to go to Hawaii than to Trinidad since its location was so close to England. He closes this letter with an apology for the late Christmas present.

In February, 1941, George's transfer to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii took place and he received his field training. George was so proud to be a pilot that he sent his mother a photograph of himself in his aircraft which he autographed simply, "Lucky, lucky me!"

Between February, 1941, and December 7, 1941, Whiteman's life is fairly well shrouded in mystery. He was assigned to the Eighteenth Pursuit Group, Forty-Fourth Pursuit Squadron at Wheeler Field on Oahu. The Eighteenth's crest and motto, "UNGUIBUS ET ROSTRO" meaning "With Talons and Beak," proudly adorned his stationery. On January 3, 1941, George completed a course on chemical warfare and was named the squadron's chemical warfare officer shortly after.

The last letter received by the family was postmarked April 3, 1941, from Honolulu, Hawaii. This was received in June by Sue Whiteman Berry. The contents concerned the death of an acquaintance, the location of a mutual friend at Pearl Harbor, how his station "gets on my nerves" although he preferred Hawaii over his only other alternative, Trinidad, Tobago. He wrote of taking up the sport of golf again, how even though he made more money as a lieutenant, he still owed $700.00 in debts which he was paying off $100.00 at a time. He joked that he was "going into wine, women, and song and forget about worry. Only trouble is that there aren't any women here." He closes with his address and the hopes that his friend, Howard, would write him.

Not having any word from George since June, Sue contacted the Red Cross. The Red Cross then contacted Whiteman and suggested in October, 1941, that he write home. Sue still has the Red Cross response. She and her husband, Ray Berry, had planned on visiting George in Pearl Harbor. She believes that the men stationed on Oahu had an inkling that something could happen and perhaps that is the reason her brother failed to respond.

Although Whiteman was assigned to Wheeler Field, his squadron also had planes at Bellows Field on the northeast coast of Oahu. The planes available to the squadron were the P-36 and P-40. The Curtiss P-36a Hawk had been purchased by the Army Air Force in 1938 at a cost of $23,000 each. By the time of Pearl Harbor, the plane was obsolete and mostly saw service in foreign air forces as an export. The other plane was the Curtiss P-40c and d Tomahawk. This plane was equipped with an Allison V-1710-34 engine, four 50-caliber machine guns in the wings, two 30-caliber machine guns in the nose, and heavier armor plating protection for the pilot. This was the aircraft that faced the Japanese Zero Fighter on December 7, 1941.

The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero-Sen had been designed by an American-trained engineer, Jiro Horikoshi. The plane first flew on March 19, 1939, and first saw combat on July 21, 1940, in China. It proved to be an immediate success. American General Claire Chennault took notes on the plane. He relayed this information to the military authorities in Washington, D.C. His warnings and information were ignored. No one in Washington believed or was willing to accept the fact that the Japanese had invented a superior fighter. This plane would remain supreme in the Pacific and in China until the tactics of Chennault's American Volunteer Group, "Flying Tigers," proved superior over the Japanese tactics and newer and more powerful aircraft were produced. The Zero could out-climb, ont-run, and out-maneuver the American planes that existed at that time. It was lightly armed with four 7.7 mm machine guns. It had no armor plating to protect its pilot or self-sealing fuel tanks, nor could it power dive without the fragile wings ripping off.

As dawn broke over Oahu on December 7, 1941, 353 Japanese planes were winging their way toward their assigned targets. They were to attack the ships in the Harbor, Schofield Barracks, Fort Shafter, Ewa Airfield, Kaneohe Airfield, Hickam Airfield, Wheeler Airfield, and Bellows Airfield. At 7:55 a.m., the first bomb fell on Pearl Harbor. At 8:02 a.m., the Japanese attacked Wheeler Airfield. The 52 P-40s and 39 P-36s were destroyed and the base laid waste. The Japanese had begun the attack with great success.

When the bombing began, Whiteman was in his room at the Bachelor Officer's Quarters to which he had moved in November. He stepped out on the veranda, looked in the direction of Pearl Harbor and immediately guessed what was up. His maid, Kathryn S. Miller, saw him rush back in and, within five minutes, he was speeding away in his car toward Wheeler Field. She noted that he had been in such a hurry that he had changed into his service uniform and not his flying suit.

Whiteman drove the 25 miles to Wheeler Field. Upon arriving and seeing the destruction at Wheeler Field which left him with no plane to fly, he quickly raced over to Bellows Field. At Bellows, a lone Japanese Zero strafed the field at 8:30 a.m., wounding a medical orderly. Another orderly drove a mile to the base commander's house and informed him of the attack. The commander immediately ordered the dispersal of the 20 planes stationed there that morning, only 12 of which were P-40s. Private Ray McBriarty was typical of the men at Bellows that morning. He saw the Japanese plane attack, incorrectly assumed it was an Army AT-6 trainer performing an exercise, then continued on his way to church. Corporal Kolom sat under the wing of a plane writing a letter home. He looked up just in time to see nine Zeros led by Lieutenant Shigematsu, the fighter pilot leader, attack a B-17. The B-17 was one of 14 bombers expected from the mainland that day. Upon arriving, they found themselves in the midst of the attack. This particular B-17 was piloted by Lieutenant Robert Richards. Being practically out of fuel, he decided to make an emergency landing on the 2600-foot runway at Bellows Field. The nine Japanese planes flying in V formation took turns shooting at the lumbering bomber as it came in. Three of the men aboard the plane were wounded, but Richards managed to make a safe landing. At this point, Hickam Field notified the tower at Bellows Field that an attack was under progress. The time was 9:00 a.m. The next events took place all at once.

Kolom ran towards a parked plane that a pilot was frantically trying to start. Japanese planes appeared from everywhere it seemed. One Zero strafed the P-40 to which Kolom was heading. The pilot slumped in the cockpit. He continued on, but when another Zero dove on the hapless plane, he hid under the wing. It was from here that he saw Whiteman's car race up to the runway. Charles King was busy loading ammunition into the P-40s. He was one of the few to heed the warning of Major L. D. Waddington, the base commander, to ready the planes. He, too, saw Whiteman pull up in his car. Whiteman turned off the ignition, jumped out of his car, and raced to one of the P-40s. He told the men loading ammunition into the guns to get off the wing and he would fly the plane as it was. He started the engine and, with the plane's engine still cold, taxied out onto the runway. In fact, Whiteman had been so quick to leave that the armorers did not have time to install the gun cowlings back on the wings. As George began his takeoff run, he was immediately spotted by two Japanese Zeros. At least two, if not three, enemy planes swooped down. He managed to take off and got approximately 50 feet into the air when the Zeros opened fire on him.

Whiteman attempted to turn inside the Japanese planes on his tail as he had been taught to do when under attack during takeoff. The writers of the air combat tactics book had ignored the warnings about the Zero, and the P-40 certainly wasn't capable of out flying the Zero. The P-40 was too slow and unmaneuverable to succeed in this tactic. The Japanese fighters opened fire hitting the engine, wings, and cockpit. The plane burst into flames. Whiteman was apparently still alive and tried to make a belly-landing on the beach north of the field. Instead, he crashed and the plane was consumed by flames. King, Kolom and many others tried to reach the plane in an attempt to save him, but it was too late. Whiteman had died.

The attack ended around 10:00 a.m. that morning. The Japanese had managed to sink or seriously damage 18 ships, destroy 188 planes, and damage 159 other planes. The Navy had 710 men wounded and 2008 killed. The Marines had 69 wounded and 109 killed. Civilian casualties were 35 wounded and 68 killed. The Army had 365 wounded and 218 killed, including George Whiteman. Fifteen Medals of Honor, 60 Navy Crosses, five Distinguished Service Crosses, and 65 Silver Stars for acts of valor were awarded. The Japanese lost 29 planes and 100 men.

The Adjutant General in Washington, D.C. was sent the following telegram: "Following Second Lts Air Corps Res Killed in Action Seven Dec at Bellowsfield (sic) COLON Naught Dash Three Nine Nine Six Eight Three STOP Nearest Relative John C Whiteman Six Two Three W Twenty Fourth Street Sedalia Missouri COMMA Relationship Unknown COLON Hans C. Christiansen Naught Dash Four Naught Six Four Eight Two Nearest Relatives Mr. and Mrs. Peter C. Christiansen One Naught One Court Street Woodland Calif Father and Mother STOP Relatives Both Officers Notified By Radio STOP Further Details Later. Short 8:22 PM"

On the evening of December 7, 1941, at 10:13 p.m., Mrs. Whiteman received a telegram informing her of her son's death. It read: "Second Lt. George A Whiteman killed in action this date. STOP Further information will reach you from War Dept Washington. Sincere Sympathy Short C. G. Ft Shafter, TH 10:10 p.m." TH was the abbreviation for Territory of Hawaii. D. Kelly Scruton of The Sedalia Democrat interviewed Mrs. Whiteman that evening. When asked about the telegram, she said "It's hard to believe. There might have been a mix up, it all happened so quickly. There's nothing we can do but wait further news from Washington." She added, "It might have happened anytime, anywhere. We've got to sacrifice loved ones if we want to win this war." She also gave Scruton the photograph of George sitting in his aircraft with the inscription, "Lucky, lucky me." This photo has become known internationally and is frequently used in articles referring to Whiteman.

The second telegram was sent from the War Department on December 8, 1941. It read, "Deeply regret to inform you official information received your son Second Lieutenant George Allison Whiteman Air Corps killed in action December seventh in Hawaii STOP No decision now possible as to when the remains can be returned STOP You will be further advised when the shipment is contemplated. Adams The Adjutant General."

Second Lieutenant George Allison Whiteman has been recognized as the first known American airman to become a casualty of World War II. He was 22 years old. For his brief part in the war, Whiteman was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry, the Purple Heart for wounds resulting in his death, the American Defense Medal for joining the military between 1939 and 1941 with a foreign service clasp for a length of service outside the United States, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with one bronze star for being in the Central Pacific Campaign between December 7, 1941, and December 6, 1943, and the World War II Victory Medal for service between December 7, 1941, and December 31, 1946. The Silver Star is our nation's second-highest posthumous award.

Gene Whiteman, George's brother, said later that the battery on his family's radio had gone out the weekend his brother died. The neighbors talked about an attack on Pearl Harbor, but the family didn't believe it, he said. At the time, they had a Movietone movie show of the diplomats from Japan in Washington, and the Japanese were supposed to be making peace.

On December 9, 1941, Second Lieutenant George Allison Whiteman, Serial Number 0-399-683, of the U.S. Army Air Corps 44th Pursuit Squadron, 18th Pursuit Group, Bellows Field, was temporarily interred in Plot 4, Row F, Grave 30 at Schofield Barracks Cemetery, Schofield Barracks, Territory of Hawaii. Buried on his left in Grave 30 was Second Lieutenant Louis G. Moslener, Serial Number 0 409 917 of the 85th Reconnaissance. Buried on his right in Grave 29 was Second Lieutenant Hans C. Christiansen, Serial Number 0 406 482 of the U.S. Army Air Corps 44th Pursuit Squadron.

Memorial services honoring George in Sedalia were conducted on Sunday, December 28, 1941, at the East Sedalia Baptist Church at 2:30 p.m. The Reverend Walter P. Arnold, pastor of the church, paid tribute not only to Lieutenant Whiteman, but also to other Pettis County youths who had lost their lives in this great conflict.

|

|

| Lt. George Whiteman, WAFB |

|

| Lt. George Whiteman's Birthplace, Sedalia, Missouri |

Three 44th Pursuit Squadron 3 pilots among heroes at Pearl Harbor

by Casey Connell

18th Wing Historian

12/7/2011 KADENA AIR BASE, Japan

Seventy years have passed since Dec. 7 brought the calamity of war to an American territory, which led to a four-year struggle and more than 418,500 American causalities. Amidst the many heroic actions rendered by service members from all services that infamous Sunday morning, three Army Air Force pilots of,the 18th Pursuit Group, 44th Pursuit Squadron attempted to get airborne to defend their country against a foreign foe.

Two of the three 44th pilots ultimately gave their lives, while their other wingman made a crash landing into the sea, surviving the ordeal but severely wounded. Today, on Kadena Air Base, the 44th Fighter Squadron pilots trace their proud lineage back to those three pilots and their comrades who were to fly and fight across the Pacific.

The 44th Pursuit Squadron was stationed at Bellows Field, Hawaii, when the Imperial Japanese Navy commenced its attack against American forces. Founded as a casual training camp on Aug. 7, 1941, to provide basic training for newly arrived casuals or recruits, Bellows Field was also home to the 86th Observation Squadron. The 86th Observation Squadron had six O-47 observation monoplanes and two O-49 Vigilant light observation aircraft, in addition to one squadron of P-40 Warhawk fighter aircraft. The three 44th PS pilots, 2nd Lt. Hans C. Christiansen, 1st Lt. Samuel W. Bishop and 2nd Lt. George A. Whiteman, were at Bellows undergoing gunnery training on their P-40 Warhawks. One of the objectives of the Imperial Japanese Naval Force was to annihilate land-based airpower on Oahu by seizing control of the air and coordinating with Japanese D3A Val dive bombers in attacks against Hickam, Wheeler, and other airfields. The Japanese achieved their tactical goal of total surprise.

Dozens gather to honor 2nd Lt. George A. Whiteman, namesake of Air Force base

|

| Glenn Berry, of Allison, left, and George Williams, of Bolivar, both nephews of 2nd Lt. Whiteman, lay a wreath at his gravesite during Saturday’s ceremony at Memorial Park Cemetery. |

|

| Stan DeFoe, of Sedalia, a retired Navy captain, salutes as the American flag is posted during Saturday’s memorial service for 2nd Lt. Whiteman. |

Under a flagpole, near a nondescript grave, dozens of people gathered Saturday morning at Memorial Park Cemetery to honor 2nd Lt. George Whiteman — Whiteman Air Force Base’s namesake.

The 22nd Memorial Wreath Laying Ceremony was put on by the Whiteman Military Affairs Committee and the Sedalia Area Chamber of Commerce. Dianne Simon, who served as coordinator of the event, opened the ceremony by recognizing several members of the Whiteman family, military members and City of Sedalia officials.

Whiteman, a Sedalia native, was honored because he was one of the first American airmen killed during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Members of the 40 & 8, Voiture 333, solemnly placed their blue hats over their hearts as members of the Smith-Cotton High School Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps honor guard presented the colors as the national anthem was sang. Simon then introduced Brig. Gen. Robert E. Wheeler as the guest speaker.

Wheeler is the commander of the 509th Bomb Wing at Whiteman AFB, where he is responsible for the combat readiness of the Air Force’s only B-2 wing.

“I am deeply honored to be here,” Wheeler said, “and I am honored to be a part of this heritage-rich area.”

Wheeler said Sedalia has a proud and storied history before giving a brief history on the base and Lt. Whiteman’s military service.

“He is the perfect namesake for our base.”

Wheeler said Whiteman had an “uncommon” IQ of 128 and walked miles to school.

“Today we salute Lt. Whiteman,” Wheeler said.

Following Wheeler’s speech, members of Whiteman’s family laid a patriotic-themed wreath on his grave. The ceremony continued with the retirement of the colors by VFW Post 2591 as Simon read the history behind why the American flag is folded into a perfect triangle.

“The flag folding ceremony represents the same religious principles on which our country was originally founded,” Simon said.

As the men completed the folding, Simon said “the end result takes on the appearance of a cocked hat, ever reminding us of the soldiers who served under Gen. George Washington and the sailors and marines who served under Capt. John Paul Jones who were followed by their comrades and shipmates in the Armed Forces of the U.S., preserving for us the rights, privileges, and freedoms we enjoy today.”

The ceremony concluded with a Whiteman AFB T-38 Four Airship Missing Man Flyover and the firing of three volleys of shots by members of the VFW.

Sedalia resident Stan DeFoe, 91, attended the ceremony in his crisp, white Navy uniform. DeFoe, retired Navy captain, served 32 years in the military and is a cousin of Whiteman.

DeFoe said he enjoyed the entire ceremony because “it is a remembrance,” but the flag-folding is his favorite part.

“It is a beautiful thing,” he said.

WHITEMAN AIR FORCE BASE, Mo. -- Cheryl Sisk and Glenn Berry pose next to a painting of their uncle, 2nd Lt. George Whiteman, at the 509th Bomb Wing headquarters building Sept 7. They also visited a B-2 Bomber and historical Oscar - 01 launch control facility during their tour. Sedalia Army Air Field became Whiteman Air Force Base Dec. 3, 1955 in honor of Lieutenant Whiteman. A native of Sedalia, the lieutenant was one of the first American Airmen killed in World War II when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Dec. 7, 1941. During the attack of Bellows Air Field, Oahu, Lieutenant Whiteman managed to reach his fighter aircraft. While attempting to take off, enemy fighters attacked his plane. Lieutenant Whiteman's P-40 crashed, fatally injuring him. By the time rescue teams reached the aircraft, the lieutenant had died. (U.S. Air Force Photo/Tech. Sgt. Samuel A. Park)

From a Bellow Blog below..

Aloha All,

Thought you might find unique some interesting connections between Bellows Field on 7 Dec 1941 and two later events.

As the eight Japanese second wave Hiryu fighters swept across Bellows Field, George A Whiteman prepared to get in the air. His crew chief pointed out the enemy, and Whiteman gunned the P-40's engine to taxi to the end of the runway. The initial fighter missed him and Whiteman started his roll. Whiteman got in the air, was hit and banked left, and crashed at the end of the runway.

B-2 bombers refueled en route to Afghanistan in this war against Terror....from Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, named for our boy from Bellows Field.

After George Whiteman's crash, Sam Bishop got his P-40 airborne but was hit by the same Zero that got Whiteman. Bishop crashed in the ocean north of Bellows and waded ashore.

Another pilot, Hans C. Christensen, viewed the Japanese planes coming in and got onto the wing of his P-40, helped by 86th Observation Squadron pilot, Phil Willis. His plane was strafed and Christensen was killed.

On 22 November 1963, Phil Willis was on the parade route taking photos as President John F Kennedy passed. The car turned left by the Texas School Book Depository and Willis took his last photo as the car turned. That photo was used in the Warren Commission and other reports as it shows the 6th Floor Window.

Unique connections...

| John Casey Whiteman, Sr | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Earlie Sanders Whiteman | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Mother: Laura (Lula) BRECKENRIDGE b: 11 Jan 1867 in ,, Missouri, USA

Marriage 1 Earlie SANDERS b: 21 Oct 1896 in Pilot Grove, Cooper, Missouri, USA

Married: ABT 1918 in Kansas City, Jackson, Missouri, USA

Children

George Allison WHITEMAN b: 12 Oct 1919 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA

George Allison WHITEMAN b: 12 Oct 1919 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA  Living WHITEMAN

Living WHITEMAN  Living WHITEMAN

Living WHITEMAN  John Casey WHITEMAN b: 1923/1924 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA

John Casey WHITEMAN b: 1923/1924 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA  Paul A. WHITEMAN b: 1925 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA

Paul A. WHITEMAN b: 1925 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA  Lee Sanders WHITEMAN b: 16 May 1927 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA

Lee Sanders WHITEMAN b: 16 May 1927 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA  Carl Otto WHITEMAN b: ABT 1928 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA

Carl Otto WHITEMAN b: ABT 1928 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA  Living WHITEMAN

Living WHITEMAN  Marshall Earl WHITEMAN b: 31 Dec 1933 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA

Marshall Earl WHITEMAN b: 31 Dec 1933 in Sedalia, Pettis, Missouri, USA  Living WHITEMAN

Living WHITEMAN Brother KIA, Korea

PFC Marshall Whiteman, USMC

Sgt. Lee Sanders Whiteman, USMC, brother to 2Lt. George A. Whiteman

Rembember George Whiteman's Legacy

| April 30. 2015 By Nicole Cooke - ncooke@civitasmedia.com

It’s been almost 60 years since Sedalia Air Force Base was renamed to Whiteman Air Force Base, and a local group has brought the community together to honor the base’s namesake. On Dec. 7, 1941, Earlie Whiteman received the news that her son, 2nd Lt. George Whiteman, was killed in action during the attack on Pearl Harbor, making him the first pilot killed in aerial combat in World War II. On Dec. 3, 1955, as a tribute to the Smith-Cotton graduate’s sacrifice, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Nathan F. Twining changed the base’s name in his honor. As the years have passed, the history of the base’s name has begun to fade, so the Sedalia Chamber Leadership Class and Military Affairs Committee have come together to create a memorial for George Whiteman. The idea began with Terri Ballard, a former member of the committee. “The military was close to my heart. I’ve had grandfathers, father and son who’s been in the military,” Ballard said. “In research when I was involved with the committee, and especially being a mother of boys who have been in the military, reading some of the stuff his mother had said, it just really tugged at me. … We really don’t have anything that honors that, people don’t know that connection and to me it’s important that we preserve it.” The project was then brought to the Leadership Class, and the group chose the memorial as its 2014 class project, which meant it had to be completed in the class’ nine-month class schedule. “I’m not a Sedalia native, but I’ve lived here for 20 years, and I didn’t know, nor did a lot of people in Leadership Sedalia, we weren’t aware where the Whiteman Air Force Base name came from,” said Mark Nelson, head of the adult Leadership Class. “So while we were about to do this project, we also learned a lot about the history of Sedalia and Whiteman Air Force Base as well.” Ballard found that the Whitemans’ home is still in Sedalia and in close proximity to George Whiteman’s burial site. With Katy Park in between, it was decided to make it a three-part memorial, which includes plaques at all three sites to educate visitors. The project started out simply as plaques at each of the three sites, due to budget restrictions, but soon several local donors and businesses stepped forward. Sedalia Parks Department is helping with a lot of the funding, plus helped with landscaping, Fischer Concrete supplied concrete for the sculptures’ base, Stone Laser Imaging helped with the plaques, members of the Whiteman family donated money — and many of them will be in attendance at the dedication — and local artist Don Luper was contacted to create the sculptures. “It all came together,” said Committee Chairman Dianne Simon. “Everyone was really willing to help out and get this up and running in the time frame we had. … And everything has been done locally.” Luper purchased models of a B-2, the iconic stealth bomber housed at WAFB, and a P-40B, the plane George Whiteman flew in WWII. Each of the steel sculptures, which have taken him about four months to complete, are as close to scale as possible. “It’s for a great cause,” Luper said. “He was the first airman killed in World War II, and there’s nothing in Sedalia that talks about that. There’s definitely a need for it. “… The measurements on the B-2 are just mind-blowing. … For the most part I got the lines off from those measurements on the models, but sometimes you just step back and realize something’s not right, and you have to throw a little artistic license in there.” Luper said he enjoyed working with steel, one of his favorite mediums, and he liked working with the “elegant curves” of the P-40. Simon said once the sculptures are in place at Katy Park, the B-2 will be pointing toward WAFB, while the P-40 will be directed toward the Whitemans’ home. “This is an actual physical reminder that (visitors) can see and they can learn what (George Whiteman) did and who the person is behind the name,” Simon said. The annual Wreath Laying Ceremony will take place at 11 a.m. Saturday, May 16 — Armed Forces Day — at Whiteman’s gravesite in Memorial Park Cemetery. The Whiteman Corridor dedication will take place immediately following at Katy Park, located at the corner of 24th Street and Grand Avenue. Nicole Cooke can be reached at 660-826-1000 ext. 1482

Whiteman Air Force Base History

History

U.S. Army Air Corps officials selected the current site of the base to be the home of Sedalia Army Air Field in 1942. The base was one of eight sites dedicated to training glider pilots (specifically, those flying the Waco CG-4A) for combat missions performed by Troop Carrier Command. For a brief time following the end of World War II, the airfield remained in service as an operational location for Army Air Force C-46 and C-47 transports. In December 1947, the base was placed on inactive status and the name changed in June 1948 to Sedalia Air Force Auxiliary Field.

After initially being considered as a possible site for the Air Force Academy, in August 1951, Strategic Air Command selected the base to be the site of one of its new bombardment wings. The base was redesignated Sedalia Air Force Base, and in October 1952, SAC activated the 340th Bombardment Wing with both B-47 Stratojet bombers and KC-97 Stratotanker air refueling aircraft assigned.

In October 1955, members of the wing saw the base name change to Whiteman AFB, in honor of 2nd Lt. George A. Whiteman, a Sedalia native. Whiteman was one of the first American Airmen killed in combat during World War II, when his P-40 fighter, the “Lucky Me,” was shot down during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

As B-47s were phased out of the U.S. Air Force in the early 1960s, Whiteman AFB’s mission shifted from aircraft to the Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile. In June 1961, officials selected the base to become the command’s fourth Minuteman missile wing, the 351st Strategic Missile Wing. The 340th was inactivated in September 1963, and the missile wing went on full operational alert in June 1964.

In the late 1980s, the 351st fielded the first female Minuteman missile crew, the first male and female Minuteman crew, and the first squadron commander to pull alert in the Minuteman system.

On Jan. 5, 1987, Rep. Ike Skelton revealed that the first deployment of the B-2 Advanced Technology Bomber would be at Whiteman. Beginning in 1988, a massive construction wave that created new buildings designed for B-2 operations, maintenance and support activities swept over the base. This buildup coincided in 1991 with the dismantling of the 351st’s missiles, as required by the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty.

On Sept. 30, 1990, the 509th Bomb Wing moved its headquarters from Pease Air Force Base, New Hampshire, to Whiteman, albeit in an unmanned and nonoperational status. With the end of the Cold War, two new organizations rose, one of which was Air Combat Command, the 509th’s new higher headquarters. On April 1, 1993, the 509th officially began manning and equipping the wing at Whiteman.

Then, Dec. 17, 1993, the event that Whiteman had long-awaited finally came. On that day, at approximately 2 p.m., a jet swooped from the sky and landed on the Whiteman runway. Amid much fanfare, the first operational B-2, the “Spirit of Missouri,” had arrived. Less than a week later, Dec. 22, 1993, Whiteman again made history as it generated the first B-2 sortie from the base.

On July 31, 1995, the 351st Missile Wing officially inactivated, ending its 33-year association with Whiteman AFB.

Throughout its history, the base has always been at the forefront of national defense. The B-2 made its highly successful combat debut in March 1999 during Operation Allied Force. The 509th subsequently flew combat sorties from Whiteman and forward-deployed bases in support of operations Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan) and Iraqi Freedom.

On Feb. 1, 2010, the 509th Bomb Wing at Whiteman AFB became part of the newly created Air Force Global Strike Command. The wing’s pre-eminent role in the projection of American military power was again demonstrated in March 2011, when B-2s from Whiteman struck targets in Libya as part of Operation Odyssey Dawn.

In 2013, the Air Force celebrated the “Year of the B-2,” marking 20 years since the first B-2, the “Spirit of Missouri,” arrived at Whiteman Air Force Base, where it and 19 other B-2 Spirits to this day continue to carry out the mission of global assurance and deterrence. Miner hero

December 6, 2016 by 5 Comments

|