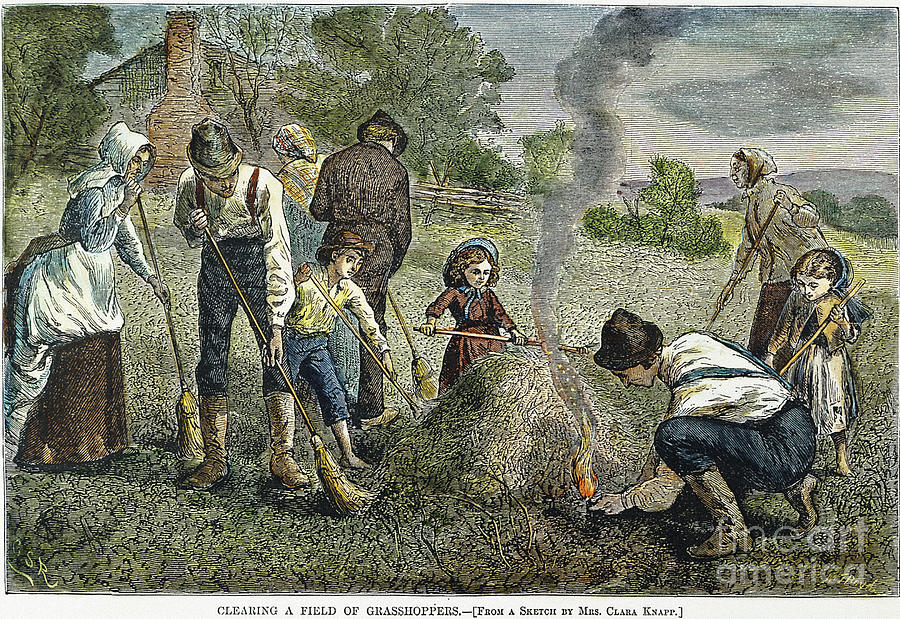

"It was so bad that they started eating Grasshoppers..." Warrensburg, MO 1875

"A nightmare unimaginable, rarely mentioned in history books, that caused such damage that huge areas in several states were to be abandoned, often with the aid of troops. A sudden unexplained migration of frontier population to the coastline. The year was 1875 and it soon was to be called the “Year of the Grasshopper“.

“It was the year 1875 that will long be remembered by the people of at least four states, as the grasshopper year. The scourge struck Western Missouri April 1875, and commenced devastating some of the fairest portions of our noble commonwealth." It was reported that the Missouri Pacific Railroad Depot in Warrensburg had 3 inches of grasshoppers on the ground......

November 08, 1911

MISSOURI GRASSHOPPER YEAR

How the Pest Interfered With Travel and Ruined Business, (Kansas City Star.)

Kansas has sometimes wished that some of the other rightful heirs to unpleasant legacies would come forward and claim their share of the inheritance. Grasshoppers, for instance, do not belong solely to Kansas. I.W. Wood recalls the year that grasshoppers were distinctly a Missouri pest. It was in 1875, the year following the blight Kansas suffered from the all-devouring hordes. Mr. Wood went to Warrensburg that year. The track laid on the surface, as the early engineering placed it, met many grades. Grasshoppers had taken the land. Every time a train came to a slight grade it was necessary for the passengers and train crew to get out of the train and shovel the insects from the right of way; crushed on the rails the track became too slick for the locomotive's progress. There was a cut through which the train passed near Warrensburg, and there, Mr. Wood recalls, was stationed a section gang with shovels scooping out the wind rifts of insects. There was more or less bravado in the offer a bank in Warrensburg made of $1 for every bushel of grasshoppers brought to the bank. Next day the bounty was reduced to 50 cents and the day after the bank announced that it was out of the market for grasshoppers.

The woolen goods house for which Mr. Wood traveled at the time was dissatisfied with the business he was doing in the West and was prone to discredit, his account of the adverse conditions in Missouri and Kansas. Mr. Wood mailed a large packing box with dead grasshoppers and expressed to his firm In the East, His house said nothing more about the lack of trade in the West.

|

Just 2 miles East of Warrensburg, MO grasshoppers were so thick on the tracks that shovels and crews were employed to help clear the tracks, otherwise the rails were too slick for the trains.

|

The insects arrived in swarms so large they blocked out the sun and sounded like a rainstorm! In the hardest hit areas, the red-legged creatures devoured entire fields of wheat, corn, potatoes, turnips, tobacco, and fruit. The hoppers also gnawed curtains and clothing hung up to dry or still being worn by farmers, who frantically tried to bat the hungry swarms away from their crops."

"Attracted to the salt from perspiration, the over-sized insects chewed on the wooden handles of rakes, hoes, and pitchforks, and on the leather of saddles and harness, and wool from live sheep. Tree bark would be stripped off of the trees, leaving tree trunks barren. There would be so many locusts that the locomotives would be stopped cold, not being able to get traction because the insects made the rails too slippery.

“According to the first-hand account of A. L. Child transcribed by Riley et al. (1880), a swarm of Rocky Mountain locusts passed over Plattsmouth, Nebraska, in 1875. By timing the rate of movement as the insects streamed overhead for 5 days and by telegraphing to surrounding towns, he was able to estimate that the swarm was 1,800 miles long and at least 110 miles wide. Based on his information, this swarm covered a swath equal to the combined areas of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont.”

A swarm of locusts that is 1800 miles long and 110 miles wide !!

The state journal., June 25, 1875(Jefferson City, Mo.)

Los Angeles Herald, Volume 4, Number 57, 1 June 1875

Grasshopper Crop in Missouri.

Lexington, Mo., May 28.— "There are millions of them," is the report from most all parts of this county. The grass and dog-fennel will not last much longer, and as soon as they are gone the grasshoppers will make an onslaught on the crops. Their wings are developing very fast, and it will not be many days till the largest proportion of them will be able to emigrate.

Richmond, Mo., May 28th —Since the heavy rain of Wednesday the hoppers are travelling in a - southerly direction, eating everything as they go. There is no garden in this locality that they have not eaten up.

This item in the Bates County Record, Butler, Mo., of June 19, 1875 copied from the Warrensburg, (Mo.) Daily News, afforded in its wit or wisdom interesting reading to the grasshopper food faddists of the day:

LOCUSTS AS FOOD

Practical Test of the Matter Yesterday afternoon Messrs. Riley and Straight determined to test the cooked locust question, in regard to its adaptability as food for the human stomach. Getting wind of the affair and being always in haste to indulge in free feeding, we made bold to intrude ourselves on our scientific friends. We found a bounteous table spread, surrounded by the gentlemen named, accompanied by Mrs. Straight, and Mrs. Maltby. Without much waste of ceremony there were five persons seated, and we were helped to 'soup which plainly showed its locust origin and tasted like chicken soup—and it was good; after seasoning was added we could distinguish a delicate mushroom flavor—and it was better. Then came battercakes, through which locusts were well mixed. The soup banished silly prejudice and sharpened our appetite for this next lesson, and battercakes disappeared also. Baked locusts were then tried (plain hoppers, without grease or condiment), and either with or without accompaniments, it was pronounced an excellent dish. The meal was closed with desert a la "John the Baptist"—baked locusts and honey—and, if we know anything we can testify that that distinguished Scripture character must have thrived on this rude diet in the wilderness of Judea. We believe this is the first attempt at putting this insect to his best use, and the result is not only highly satisfactory to those brave enough to make the attempt, but should this insect make his visit oftener and cause greater destruction future generations will hail its presence with joy. It will be a jubilee year—like manna in the wilderness, or quails in the desert—food without money and without price.

Frank Behm, a prominent farmer and stockman of Chilhowee township, is the owner of one of the beautiful country places in this section of Missouri. He is a native of Illinois, born in Chicago in 1858, a son of Henry and Lena Behm. Henry Behm was a skilled cabinetmaker and for twenty-one years followed his trade in the city of Chicago. In 1870, he moved with his family to Nebraska, where he homesteaded one hundred sixty acres. Here the Behm family endured countless hardships and misfortunes. During the grasshopper visitation, 1874 and 1875, their entire crops were destroyed and the Behms were left in destitute circumstances. They wore sow sacks for clothing and the father made wooden shoes for each member of the family. Supplies could be obtained at a place thirty-six miles distant from their dugout, provided, of course, that one had the money, for no one sold on credit. The family, in consequence, really suffered from lack of food many, many times in the new Western home. The father and mother died there and later, their son, Frank, left Nebraska and moved to Iowa, where he engaged in farming for twenty-eight years. The first teacher of W. T. Gibson was Joe Goodwin. Another instructor, whom he had in his boyhood days, was Palmer Smith. Among his schoolmates he recalls the Goodwin. Patrick. McDonald, and Cooper children. He completed his education at McKendree College at Lebanon. Illinois and after leaving college, returned to his father's farm and engaged in the pursuits of agriculture. He vividly recalls the period of the destructive grasshoppers in 1874 and 1875 and the too frequent prairie fires, which he helped fight until ready to drop from exhaustion.

“In his eighth annual report Mr. Riley (then state entomologist of Missouri) thus estimates the loss in the various counties of Missouri in 1875: Atchison, $700,000; Andrew, $500,000; Bates, $200,000; Barton, $5,000; Benton, $5,000; Buchanan, $2,000,000; Caldwell, $10,000; Cass, $2,000,000; Clay, $800,000; Clinton, $600,000; De Kalb, $200,000; Gentry, $400,000; Harrison, $10,000; Henry, $800,000; Holt, $300,000; Jackson, $2,500,000; Jasper, $5,000; Johnson, $1,000,000; Lafayette, $2,000,000; Newton, $5,000; Pettis, $50,000; Platte, $800,000; Ray, $75,000; Saint Clair, $850,000; Vernon, $75,000; Worth, $10,000. Amounting in the aggregate to something over $15,000,000.”

Who Recalls Locust Feast?

From "The Bulletin" Johnson County Historical Society, Inc., Sep, 1979 (Vol. XV, No. 2)

If you think this year's onslaught of grasshoppers has been bad, think back to what it was like in 1875 when young boys were gathering buckets of locusts for a very unusual –but true—banquet.

The subject of Warrensburg's "grasshopper feast" came up again earlier this year with a reprint of a 1909 reminiscence by "The Country Cousin" in the Warrensburg Star Journal, January 31.

The unnamed writer was a member of the city council, and he told of a dinner at the normal school that had him feel as though the 'hoppers were yet stalking through his stomach.

The fall of 1875 [sic] brought swarms of Rocky Mountain or "Indian" grasshoppers (so named because of their copper color and bright red legs) to Western Missouri. The locusts laid eggs in the sandy, loose soil, and the following year, then hatched out in plague proportions

"Country Cousin" reported that they moved forward "like an avalanche," up from the bottoms [sic] around Post Oak. There were so many of the 'hoppers that trains were being stalled because of wheels slipping on the rails. A Warrensburg banker, A.W. Ridings, offered a reward and paid fifty cents for every bushel of grasshoppers brought to his bank at Holden and East Pine Streets. So many were brought in, however, he was forced to retract the offer.

The feast? That was the idea of Charles V. Riley, the first state entomologist in Missouri and later an entomologist with the U.S. Department of agriculture. Riley claimed that the grasshoppers could be safely eaten. Accounts differ, but "Country Cousin" said that all of the teachers in the normal school attended the banquet, with the cooking being supervised by a German clerk named Weidermeyer, who was also an excellent chef.

"First came grasshopper soup, then grasshopper pancakes served with butter and syrup; the scrambled eggs well mixed with grasshoppers; then followed pudding, spiked with the festive hopper, and finally came a pie around the edge of which the red legged grasshoppers were set around in a circle looking outward, very artistically arranged," he recalled.

Riley's account of the banquet was included in a report to the governor. In addition, details were in a paper he read before the American Association of the Advancement of Science.

Louses & Locusts In just nine years as Missouri's state entomologist, Charles Valentine Riley taught the world to value bugs by Anne McEowen

It was a swarm of bugs so large, even Moses would have shuddered. In 1874, billions of locusts munched their way across America’s plains, devouring nearly every stand of vegetation in their path. The moving horde of insects, collectively the size of California, reached the western edge of Missouri. To a nation still recovering from the destruction of the Civil War, all hope seemed lost. One man stood resolute, however, determined to stem the ravenous tide.

Charles Valentine Riley lived in Missouri just nine years, but his work as Missouri’s first state entomologist had international impact and forever changed how man would think about bugs. His compassion for farmers and detailed observations of insects made him a timely prophet with the intent to profit all who toiled in the soil.

Riley’s arrival on Missouri’s agricultural scene could not have come at a better time. From 1868 to 1877, when he served as Missouri’s official bug expert, Riley formulated a new vision for agriculture, one in which man enlisted the aid of beneficial insects and bested enemy bugs through knowledge and understanding. He not only identified the natural weaknesses of America’s locust foe, but also found in Missouri relief for French vintners threatened by a tiny aphid. Wherever locust or louse threatened, Riley applied his knowledge, skill and personality to address the plague and rose to the forefront of the burgeoning field of entomology in the process.

With a passionate nature and striking physical features — complete with handlebar mustache and wavy brown hair — Charles Valentine Riley fit his romantic name. Born outside of London, England, he immigrated to the United States as a teen. After a brief stint in the Union Army during the Civil War, he found his niche writing and drawing insects for local farming publications. His skill noted, he was promoted to editor of The Prairie Farmer, an agricultural publication of wide distribution based in Chicago.

In his 2005 book, “The Botanist and the Vintner: How Wine was Saved for the World,” Christy Campbell recalls efforts to convince the Missouri legislature to appoint a state entomologist. “New York had such a scientific ornament, so did Illinois,” representatives of the State Horticultural Society of Missouri pleaded. “Why should the great agricultural powerhouse of the Mississippi valley not have the same?”

In 1868, Gov. Thomas Fletcher appointed Riley to be Missouri’s first state entomologist, the third such state official in the nation. Only 25 years old at the time, Riley had no formal training as an entomologist. What he had was a keen sense of observation, an avid interest in insects, a talent for drawing, a proven flair for writing and the recommendation of his friend, Benjamin Dann Walsh, the Illinois state entomologist.

It was his forceful and persuasive insistence in the right of his new way of thinking — coupled with an ability to describe in words and illustrations the natural proofs he observed — that gained Riley the title “Father of Economic Entomology.” He passionately believed scientists and farmers working together could manage insects to the profit of all. It was a revolutionary idea in a time that was ripe for a change in man’s views of the natural world. Charles Darwin, with whom Riley corresponded, published his breakthrough book, “On the Origins of Species,” in 1859, just nine years prior to Riley’s appointment.

Riley traversed Missouri by train, horse and buggy, studying insects and their effects on crops. In the introduction to his first annual report as Missouri’s entomologist, Riley wrote, “Wherever I have been, from one end of the state to the other, the cordial hand has been extended, and I have found our farmers and fruit-growers thoroughly alive to the importance of the work, for they know full well that they must fight intelligently, their tiny but mighty insect foes, if they wish reward for their labors.”

Indeed, Missouri’s farmers intending for their crops to be a profitable and useful for human and animal consumption were instead being out-eaten by the indigenous insects. In his first report, Riley quotes the president of the state horticultural society, who estimated the annual loss to the state from insect depredations at $60 million. While Riley believed the amount was inflated, he conceded that if even half of the estimate was accurate, it was still an enormous loss and reasonable to expect a large portion of it could be avoided.

Jeffrey Lockwood, in his 2004 New York Times best-seller, “Locust,” summarized the first report of the Missouri state entomologist by stating that Riley “laid out his philosophy of the importance of insects, explained the need for converting losses into dollars and made the argument that farmers could never master the complexity of insect life on their own.”

Riley believed his annual reports to be of critical and timely interest to the state’s farmers, gardeners and horticulturists. He was frustrated that his writings would be buried within the often-delayed annual report of the Department of Agriculture. Perhaps affronted by the government’s lack of adequate recognition and funding for his work, Riley separately published his nine annual reports at his own expense.

Lockwood described Riley’s reports as “far superior in their scientific depth and presentation quality to anything else of the day — and, for that matter, to a great deal of modern technical publications . . .

“The reports combined the terse professionalism of technical writing with the lyrical elegance of Victorian prose, all illustrated with the finest artwork ever to grace such practical pages,” Lockwood wrote. “Indeed, these reports were the birth announcements of modern economic entomology.”

Lockwood’s “Locust” describes the import of Riley’s solution: “Within months of releasing these voracious predators, Riley knew he had achieved what has been called ‘the greatest entomological success of all time.’ This was the world’s first case of classical biological control (the suppression of an exotic pest by introducing a natural enemy from its homeland), and the method has become one of the most effective and widely used pest management strategies in modern agriculture.”

Riley’s office was the destination for much mail and packages, many of which contained bugs. Missourians and others sought Riley’s expertise to identify bugs and determine if they were harmful. Perhaps in response to the condition of the bugs he received, and truly a reflection of Riley’s practical sense of humor, his letterhead included a paragraph titled: “Directions for Sending Insects,” which included the statement “Botanists like their specimens pressed as flat as a pancake, but entomologists do not. "The French botanist Jules-Emile Planchon visited Riley in 1871 and discovered the Missouri scientist maintained a collection of living insects to observe. His description of Riley’s office is contained in Campbell’s book. “The state entomologist’s office, housed in an immense building in St. Louis, was equipped with all the latest apparatus . . . The laboratory was lined with glass cages confining a miniature menagerie which allowed [Riley] to observe hour by hour the phases of evolution of the entire insect world.”

In 1866, two years before coming to Missouri, Riley published a notice in The Prairie Farmer of a “grape-leaf gall louse.” He noted a similarity to this louse and the insects reportedly plaguing French vineyards. Although the small insect did not kill Missouri vines, it was deadly to the French vines and threatened the existence of the famous French wines and the entire economy of rural France.

During the next several years, Riley worked with his French counterpart Planchon, exchanging specimens and data on the grape-leaf gall louse, an aphid also known as “phylloxera.” Riley warned of the possible spread of the insect by transplanting infected root stocks from one vineyard to another.

The French government recognized the need to stop the bug from destroying all the vines in France and offered a 30,000-franc prize for a practical remedy. In doing so, the government unwittingly encouraged overnight “experts” with highly touted, but ineffective, liquid and gaseous remedies. Desperate in their fight against the bug, French vintners spent all on these useless concoctions. Campbell notes the directness of Riley’s response to the effectiveness of the potions available, “Charles Riley got straight to the point: ‘All insecticides are useless.’”

In 1872, Riley published a list of American vines resistant to phylloxera. Isidor Bush, owner of introduction by Planchon, and Missouri roots were shipped to France by the boxcar load.

That same year, Gov. Silas Woodson proposed the abolition of Missouri’s Office of Entomology. While the salvation of Riley’s job may be attributed to an outcry from the State Horticultural Society, or the many letters written to the governor or the columns that appeared in newspapers, it may be more to the credit of the invasion of the Rocky Mountain locust into the western counties of Missouri.For his role in addressing the phylloxera infestation, the French government awarded Riley a medal in 1874. Ironically, the resulting flood of Missouri vines into the French vineyards, while a boon to the state’s agricultural economy, initiated a new disaster for French vintners as the Missouri vine roots carried more phylloxera. By 1875, the louse had invaded nearly all of France’s wine region. Vintners there had begun widespread grafting of their vines onto Missouri root stock, whereby it has been said that Missouri’s vines saved the wine of the world.

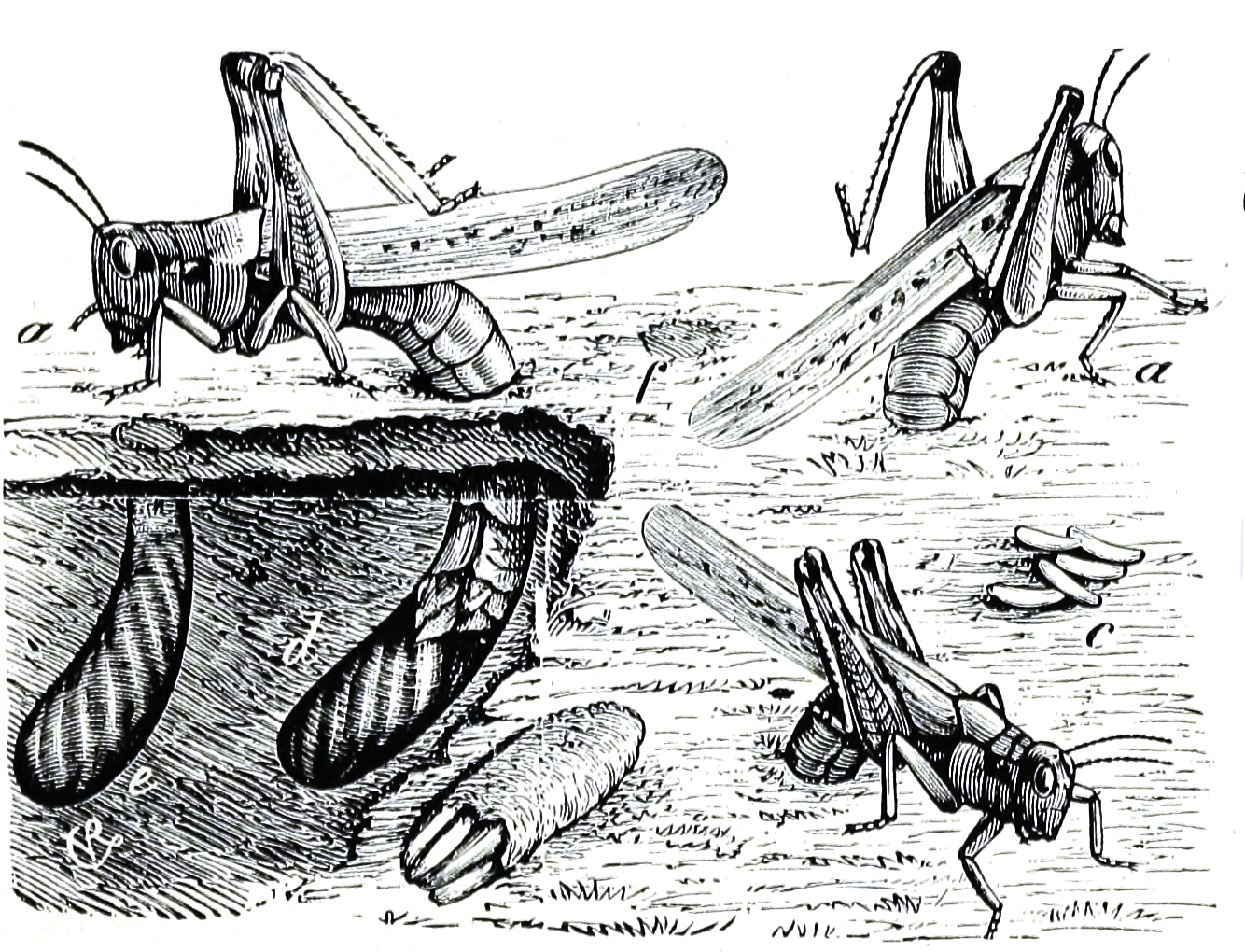

Although an individual locust was little more than an inch in length, swarms of locusts caused devastation of biblical proportion. The adult locusts traveled from the northwest, eating everything green in their path and laying their eggs by the millions in fields. The hatchlings would eat through any new growth before molting and swarming eastward causing further destruction.

Following the ravages of the Civil War, the federal government made land grants to farmers and homesteaders in Missouri and other states. Just nine years after the war, these neophyte farmers found themselves battling an enemy more powerful and invasive than any that had marched during the war.

Farmers who braved the attacking locust swarms in defense of their fields wound up not only losing their crops but also having their shirts literally eaten off their backs. Hundreds were completely impoverished, and they and their livestock faced starvation. The land in the affected counties was left so barren that it was reported that except for the warmth of the weather, one might have assumed they were observing Missouri in winter.

Riley set to work studying the locust. He collected specimens of locusts from five states, the Indian Territory and Canada, concluding that the swarm was the same migratory species. His seventh annual report to the state legislature, published early in 1875, mapped the extent of the locust swarms from southern Canada to Texas, from the Colorado Rockies to Missouri.

“The calamity was national in its character, and the suffering in the ravaged districts would have been great, and death and famine the consequence, had it not been for the sympathy of the whole country and the energetic measures taken to relieve the afflicted people,” he wrote, describing “a sympathy begetting a generosity which proved equal to the occasion, as it did in the case of the great Chicago fire, and which will ever redound to the glory of our free Republic and of our Union.”Praising the outpouring of support that allowed beleaguered farmers to survive the locust infestation, Riley wrote with characteristic Victorian flourish.

Riley’s report contains in almost reverent detail, by description and drawing, each phase of the locust’s life and reproductive stages. He also provided useful information such as the fact that the locusts would not lay their eggs in newly plowed land, nor in wet ground. Riley advised farmers to dig wide trenches around their fields as the locusts did not like to cross streams they could not jump.

Riley’s report included a review of biblical and historical locust plagues of Egypt, Africa, Asia and southern Europe as well as prior locust swarms reported in North America. He observed that on this continent, the swarms were typically contained in the West and only spread east with greater numbers and resulting damage during dry or drought seasons, as they experienced in 1874. Riley predicted in a report delivered to the governor and the Department of Agriculture that the locusts would leave Missouri and take flight back westward in early June.

In May 1875, perhaps in response to the public’s cry for government assistance or perhaps in a keen political move, Gov. Charles Hardin turned to a higher power for relief.

“Whereas, owing to the failure and losses of our crops much suffering has been endured by many . . . and if not abated will eventuate in sore distress and famine; Wherefore be it known that the 3rd day of June proximo is hereby appointed and set apart as a day of fasting and prayer that Almighty God may be invoked to remove from our midst those impending calamities . . . ” the governor proclaimed.

Riley’s prompt response to the governor’s declaration, published in the St. Louis Globe on May 19, voiced his frustration at the government’s lack of action. “Without discussing the question as to the efficacy of prayer in affecting the physical world, no one will for a moment doubt that the supplications of the people will more surely be granted if accompanied by well-directed, energetic work,” he wrote. Riley proposed a statewide monetary collection to aid people in the affected area, and further that a premium be paid for each bushel of young locusts destroyed.

Recognizing that horses and chickens ate the dead locusts and came to no harm, and having read that American Indians collected the locusts to roast and eat them, Riley proposed “entomophagy” — or, simply put, eating the bugs — as a way to reduce the number of locusts while simultaneously feeding the starving populace.

“At the Eads House in Warrensburg, Riley made his point by serving a memorable four-course meal,” recalls “Forgotten Missourians Who Made History,” a 1996 anthology of short biographies by Pebble Publishing. “The menu, which consisted of locust soup, baked locusts, locust cakes, locusts with honey and just plain locusts, apparently pleased his guests.”

Whether in response to divine intervention or just natural forces, shortly after June 3, 1875, in fulfillment of Riley’s prophecy, the locust swarms left Missouri, never to return.

In late 1876, Riley was appointed head of the newly formed U.S. Entomological Commission, which was charged with reporting ways to prevent and guard against recurring locust invasions. In 1878, the swarms of Rocky Mountain locust — a species now extinct — receded and Riley accepted the position as head entomologist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Riley resigned from his work with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1894 and became the insect curator of the U.S. National Museum. He died in September 1895 from head injuries sustained during a bicycle ride.

Collections from Charles Valentine Riley’s life, including his drawings and prolific writings, can be found in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Special Collections, in the Smithsonian Institution and at the University of Missouri-Columbia where Riley lectured for several years. His nine annual reports to the Missouri legislature are available for review in the reference library of the State Historical Society in Columbia.

McEowen is a freelance writer from Jefferson City and the wife of Rural Missouri Managing Editor Bob McEowen.

No comments:

Post a Comment