|

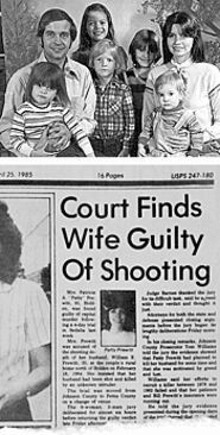

| Patty and Bill Prewitt, Holden, Missouri |

Did Patty Prewitt of Missouri kill her husband in 1984? TV show will take a new look

Bill Prewitt died in bed of two gunshots to the head during an early morning thunderstorm.

A jury said his wife and high-school sweetheart, Patricia Prewitt, pulled the trigger.

A new television series that premieres at 6 p.m. central time Jan. 7 on the Oxygen network will take a second look. The Prewitts, from Lee’s Summit before they moved to Holden, Mo., to run a hardware store, will be the subjects of the two-hour opening episode of “Final Appeal” from NBC News Peacock Productions.

The Feb. 18, 1984, murder of 35-year-old William Edward Prewitt shocked the community of Holden, near Warrensburg. The arrest of Patricia Prewitt was also shocking. People in Holden considered them an all-American couple. They mortgaged their home and paid $64,000 for the lumber and supply business. She was a PTA room mother and was elected president of the Holden Chamber of Commerce. He organized summer baseball games and was “as pleasant a fellow as you could find,” a business associate said. They had five kids.

Patty Prewitt reading Poetry

Man Killer

Did Patty Prewitt pump two bullets into her husband's head? It is a mystery that has lingered for twenty years.

By Shelley Smithson shelley.smithson@riverfronttimes.com

Bill Prewitt dozed in the front seat as his wife Patty drove their Ford Torino home in the pounding rain on a February night twenty years ago. The couple, all-American high school sweethearts, had been out late eating barbecue, dancing at a country & Western bar and playing Atari at a friend's house.

It was about two in the morning when Patty pulled up the long driveway to their two-story farmhouse north of Holden, a western Missouri town of 2,200 residents.

A soft-spoken family man whom his daughter described as so gentle "he couldn't make the dogs mind," Bill went upstairs and found four of his five children sleeping. The oldest girl had spent the night with a friend.

Patty says Bill was fast asleep when she came to bed ten minutes later. Outside, thunder and lightning crashed. Thick clouds diffused the light of a full moon.

Within an hour and a half, Bill Prewitt was dead, shot twice in the head with his own .22-caliber semi-automatic rifle.

Patty Prewitt, his wife of fifteen years -- a beautiful 34-year-old who always cracked jokes, volunteered in the PTA and served as president of the Holden Chamber of Commerce -- claimed an intruder killed her husband and attacked her at knifepoint.

Prosecutors said it was impossible to believe that a stranger found Bill's rifle in the bedroom closet and, in total darkness, loaded it with bullets that were stored in the chest of drawers -- and then shot Bill at close range while Patty slept next to him.

The state's attorney argued that Patty shot her husband then threw the rifle into a pond on the family's 40-acre farm. The rifle and her boot prints were found when the pond was drained. Her motive, said prosecutors, was lust and greed. Three ex-lovers testified that she had wanted Bill dead for years. Two of the men said she had offered them thousands of dollars to murder her 35-year-old husband.

After a four-day trial, a Pettis County jury convicted Patty of capital murder and sentenced her to life in prison without the possibility of parole for 50 years. A week after the verdict, a witness contacted Patty to say that she had seen a man in a white car watching the Prewitt house from a country road in the wee hours of that murderous night.

This same witness told police about the car -- a day after the murder -- but the lead was never investigated. Circuit Court Judge Donald Barnes refused to grant a new trial to hear the evidence.

Since going to prison eighteen years ago, Patty's effervescent personality and persistent claims of innocence have persuaded prison supervisors, cellmates, church workers and at least a dozen state legislators to lobby for her early release, now scheduled for 2036 at the earliest. She will be 86 years old. Family and friends say Patty is the victim of shoddy police work and overzealous prosecutors who cast her as a cold-hearted adulteress driven to murder.

"I did not murder my husband," Patty tells the Riverfront Times in a recent interview at the state women's prison in Vandalia, 100 miles northwest of St. Louis. "I would never have taken Bill away from our kids."

Patty Slaughter met Bill Prewitt in the seventh grade. She was a geeky tomboy, an honor-roll student who rode a horse and lived on a ranch. He was a smart, good-looking athlete who lived in a tidy house with white carpet in Lee's Summit, twenty miles southeast of Kansas City.

When Bill asked Patty out on a date their senior year, she couldn't believe he even knew her name. Patty was tall and thin, a gorgeous woman with long brown hair and sparkling eyes. She was always telling stories in her warm, country accent, talking with her hands and laughing loudly -- very loudly. Bill was quiet and shy. He was only five-foot-seven, but scrappy enough to stand out on the basketball court.

In the summer of 1968, Bill and Patty married and, shortly after, she was pregnant. He had a short-lived career as a teacher but hated it and went back to a job at the lumberyard where he had worked as a teenager. Eventually they built a home near Patty's family and had more kids.

Patty remembers those days as being close to perfect. She tended a huge garden, cooked, cleaned and played with the kids while Bill worked. "Money was always tight, but we all lived in cut-off shorts back then and nobody worried about fancy cars."

Everything changed in May 1974 while the couple was running errands in Sedalia. Patty claimed that in broad daylight three men pulled her into the bushes in a quiet neighborhood and raped her. She never reported the crime. She said she was ashamed.

She told Bill when he caught up with her later that day. At first, she says, her husband was sympathetic and "was so sad and sweet." At the trial, Patty said, "We never told anybody, not even my best friend." Later, she added, "He got more and more distant somehow. He didn't want to make love to me."

By the summer of 1976, Patty says she was lonely and confused, and she began having an affair with Ricky Mitts, a tall, dark-haired hippie who lived nearby. Patty says the affair lasted only a few months -- but long enough for her to get pregnant. Desperate to keep his family together, Bill decided to raise the baby, Morgan, as their own.

"He just didn't want anyone to know," Patty says now.

When Mitts testified against Patty nine years later, he claimed Patty offered him $10,000 to kill her husband.

Bill and Patty's marriage tumbled to its lowest point in the fall of 1976, around the time they saw a for-sale ad in the Sunday paper for a lumberyard in Holden. Bill loved the idea of owning his own lumber company, so he and Patty borrowed $60,000 from the bank and their families and bought the business.

Holden seemed like a sleepy farm town. The lumberyard was next door to the Holden City Hall and across the street from the town's tiny police station. Bill and Patty worked together while the kids played nearby.

"They were the ideal family, something out of Norman Rockwell," recalls Kirk Powell, then editor of the weekly newspaper, the Holden Progress. "She was a very bubbly kind of person. Bill was kind of shy and real quiet, but very nice."

Almost no one in town knew about their marital problems. But for almost a year, they lived separately and, Patty claims, they both cheated on one another.

Two of her relationships were short-lived flings, though another affair with a married man lasted several months. But Patty says neither she nor Bill wanted a divorce. "I didn't want to lose Bill," she says. "He was my best friend, even when I was being stupid."

It wasn't until the fall of 1978 that she says they finally mended their broken relationship. "I started throwing dishes at him," she says. "I knew if I threw dishes in my kitchen, I would get his attention."

She says they screamed at one another until they both broke down crying. Then they swept up the dishes and started rebuilding their life together. "That was the end of me cheating and him cheating."

Like the Prewitts' marriage, things could also get stormy in seemingly peaceful Holden. Teenagers drag-raced down Main, bar fights spilled into the streets after midnight and outlaws stole cars, robbed houses and sold drugs. Once, a bullet broke the front window of the W.E. Prewitt Lumber Company.

"There were people who were proud of their outlaw persona," remembers Kevin Hughes, a former Johnson County sheriff's deputy. "The kids would line up on the main drag so they could run from us and do this Dukes of Hazzardthing."

The mayor of Holden, Don Hancock, proudly called himself Boss Hogg. He drove a Cadillac and wore a white suit and a ten-gallon hat.

Still, no one in Holden worried much about crime. Patty says they left their doors unlocked until a strange man wandered into their house while their daughter was home alone, five months before Bill's murder.

Sarah Prewitt Lewis, now married with two children and living in Lee's Summit, says she was lying in her parents' bed watching TV when the man knocked on the door, then opened it and walked upstairs. "I barely had time to get under the bed," she remembers. From there, she could see his feet as he walked into her parents' closet and then opened the doors on the chest of drawers.

Patty says she reported the incident to the sheriff's office but didn't press charges because she thought the young man, who lived down the street, was mentally slow.

In the following months, the Prewitts began receiving obscene phone calls -- the last one two weeks before Bill's murder. Jane Prewitt Van Benthusen, the oldest daughter, remembers answering one of the calls. The man said, "We're going to fuck like bunnies."

After Bill's murder, officers investigated the whereabouts of the man who had been in Prewitt house. They discovered he had recently moved and was working eight hours away the night Bill was slain.

As business owners and parents, Bill and Patty Prewitt worked hard to make Holden a better community. She organized fairs and parades and volunteered as a room mother at her kids' schools. Bill was president of the city recreation league and coached soccer. When Bill and Patty found out that drugs were being sold at the high school, they and other parents formed a task force.

"My husband always called me Crusader Rabbit because I was always taking on some cause," Patty says now. "I grew up opinionated and he grew up not making a fuss."

Patty was the one who called customers who were behind on their payments, which sometimes ran into the thousands of dollars. Like other small businesses in rural America in the mid-1980s, the Prewitt Lumber Company was struggling financially.

Kevin Hughes, the former Johnson County sheriff's deputy who led the murder investigation, says Patty was upset because Bill let people run a tab even when they owed money.

But the Prewitt kids say their parents seldom fought. "They danced in the grocery store," recalls Jane, who was fourteen when her dad was killed.

On the morning of February 18, 1984, Cliff Gustin awoke at 3:50 to the sound of someone banging on his front door. Patty Prewitt was standing in the rain with her kids in her arms, frantically screaming. "Somebody pulled me out of bed," she told her neighbor. "I think Bill's been hurt."

When Gustin arrived at the Prewitt home with the Holden police chief and two reserve officers, they bounded upstairs and found Bill Prewitt dead. He was lying on his side, blankets up to his chest, and his head, shoulders and face covered in blood.

They tried the lights but they didn't work. At 4:29 a.m., Gustin flipped the main switch on the breaker box to "on." A police report said the electric clock in the house was one hour and ten minutes slow -- which meant someone threw the circuit breaker off at 3:19 a.m.

When Gustin restored the power, the lights came on in the dining room, at the top of the stairs and in the basement. At Patty's trial, Gustin, a former police officer, testified that the basement door was open. He said no one searched the house for an intruder.

When Deputy Hughes first talked to Patty on the morning of February 18, she was wearing a red coat over white pajamas and had seven cuts on her neck. "When I saw the marks on her neck, I thought, 'That looks like she did it looking in the mirror with a razor blade,'" recalls Hughes, now a private detective in Wyoming.

Patty told Hughes she had been awakened by what she thought was a clap of thunder. Soon after, she said a man pulled her onto the floor by her hair, yanked her pajama bottoms and panties off and held a knife to her throat as he got on top of her. She said she could not see the man because the room was dark.

At first, Patty told Hughes the attacker did not rape her. She now says she was sexually assaulted but didn't tell the police because she worried that her marriage would crumble again if Bill found out.

"I know it sounds crazy because Bill was dead, but he wasn't dead to me," Patty says. "I was in shock."

When the attacker left, Patty said, she tried to wake Bill but he didn't move. "He was breathing kind of ragged, kind of rattly like a kitty," she told Hughes during the taped interview the day of the murder.

She tried the lights and the phone but neither worked. After checking to make sure the kids were OK, she ran outside to the truck and grabbed a flashlight. "I shined it on Bill and there was blood down the mattress and on down the dust ruffle and I knew this was really bad," she related to Hughes.

That's when she woke her children and told them to get dressed because there was a small fire in the house. "The kids kept saying, 'Where's Daddy? Where's Daddy?' And I said, 'It's okay but we've got to get out,'" Patty told police.

She hurried her kids downstairs in the dark, helped them put on their coats and shoes, then rushed them outside and locked them in the car before running back inside to check on Bill one last time.

At the trial, Johnson County Prosecutor Tom Williams scoffed at the story Patty gave to police. "The defense would have us believe that she took the time to dress the children with Bill still hurt and alive and the rapist about..... I submit to you that is incredible."

At the Prewitt house, blood stained the white curtains and the ceiling above Bill's body. The shades were partially raised.

Hughes observed one gunshot wound above Bill's right ear. Officers later discovered two .22-caliber rifle rounds in Patty's jewelry box and a box of .22 shells in Bill's chest of drawers.

On Patty's nightstand Hughes discovered several Alfred Hitchcock mysteries and a novel called Murder in California, which he said was strikingly similar to the story he had just heard from Patty. Downstairs in the filing cabinet, he found Bill's life insurance policy.

Hughes later testified that he searched the carpet in the bedroom for hair because Patty said she had been yanked out of bed by her long brown hair. None was found.

But Patty's friend, Mary O'Roark Englert, testified she saw large amounts of hair when she dumped water out of the wet vacuum cleaner while cleaning blood from the carpet one week after the murder. If hair had been collected, it could have been analyzed for DNA using today's technology.

Englert says she also found a second shell casing that police had not recovered after a week of searching. On the afternoon following the murder, a deputy found one .22-caliber shell casing after he sat down on a wicker love seat in the bedroom and the evidence fell out.

Hours after the murder, officers also dusted -- unsuccessfully -- for fingerprints on several doorknobs. But they didn't look for fingerprints on the breaker box, a flat surface from which prints could have been more easily retrieved. The person who killed Bill would have touched the breaker box when he or she flipped the main switch at 3:19 a.m.

Hughes says officers found no signs of a stranger inside or outside the Prewitt house. "It was a rainy night, and usually, an intruder doesn't wipe their feet at the door," he says. "There were no muddy impressions."

Officers did find pry marks on the family room door and a piece of wood missing near the lock. But Sheriff Charles Norman later testified that the damage appeared old.

On the afternoon following the murder, Hughes interviewed twelve-year-old Sarah, who says she told the deputy about hearing noises in the basement and seeing a light beneath the basement door as they were fleeing the house.

Hughes says Sarah told him the story days after the murder. (None of the police reports obtained by the RFT detailed conversations investigators had with the Prewitt children.) "Patty was good about planting things into her kids' minds after the fact," Hughes says.

At 32, Sarah says her memory remains clear. Thinking the house was on fire, she had bolted into the living room to rescue her flute. "I saw this light under the basement door," Sarah recalls. "I thought Dad was down there. I remember driving to the neighbor's house thinking Dad was in the basement fighting the fire."

The basement door was closed when they left, she says.

A week after the murder, when Patty's friends were cleaning the house, they took pictures of man-size footprints on the dirt floor of the basement. "They led from the window to a little room behind the stairs," Mary O'Roark Englert says.

Police later said the footprints were not there when they arrived on the day of the murder and probably belonged to officers who searched the house.

When Deputy Hughes read Patty her Miranda rights on February 20, she didn't think she needed a lawyer. "I thought only guilty people needed lawyers," she says now.

She talked to investigators for the next seventeen hours; only the first fifteen minutes were taped. Hughes says he didn't record the full interrogation because "the sheriff's department was on a shoestring budget."

Patty claims Hughes would scream at her, then another deputy would try to calm Hughes down. At one point Patty remembers saying, "You know, I've seen Starsky and Hutch."

"Hughes had a reputation for being able to make a rock talk," Patty says. "I'm the one he couldn't break."

Hughes remembers it differently. "Patty has a lot of charm and she uses it well. She gave me the impression that she was used to manipulating men. She thought whatever she did, she was going to be believed."

At her trial Hughes testified that when he asked Patty about her affairs, she told him, "My fire burns hotter than most."

Patty insists she would never say anything that stupid.

The trial began on April 16, 1985, in Sedalia. More than 100 people from Holden, mostly Patty's family and friends, along with Bill Prewitt's relatives, packed the small courtroom. One juror remembers Patty appearing stoic as the soap opera unfolded.

Jon Hancock, the son of the mayor who called himself Boss Hogg, testified he and Patty had an affair in 1978 and that she told him she wished Bill would die in a car accident. According to Hancock, she also said she knew where his rifle was and talked about killing Bill in his sleep.

Patty says she may have said something like, "Bill makes me so mad; I wish he'd just keel over and die." But she insists she was never serious.

"If I had a nickel for every man or woman who's having an affair and said something along the lines of, 'I wish someone would shoot that SOB,' I'd be a wealthy and retired lawyer," says Phil Cardarella, the Kansas City attorney Patty retained for her defense.

Hancock wasn't the only one who claimed that Patty wanted Bill dead.

Mike Brown, a former lumberyard employee, told police in the days following the murder that Patty offered him money to kill her husband. But eight months later, in a signed statement, Brown said Deputy Hughes threatened to throw him in jail if he did not cooperate with police. He also said that Bill was present whenever Patty made jokes about having her husband killed.

Brown was not called to testify at Patty's trial. But his friend, Richard Hayes, told jurors that he and Patty had sex three times in 1978. On two occasions, he said, her kids were home, leading prosecutor Tom Williams to say Patty had "neglected her children."

Hayes told officers shortly after the murder that Patty offered to buy him a lumber company if Hayes "got rid" of Bill. Two months later Hayes signed a far more detailed statement prepared by police. In it, he claimed that Patty told him Bill beat her and that his life insurance "would make her a wealthy woman."

Patty insists that she never asked anyone to kill her husband but concedes she told her lovers that Bill beat her so "they wouldn't think badly of me."

At the trial, Hayes admitted that an assault charge was pending against him when he made statements to police. Shortly after, the charges were dropped.

On the stand, Ricky Mitts, the hippie who lived down the street from the Prewitts, said Patty feared losing custody of the kids if she asked for a divorce. He also said Patty claimed Bill beat her, but he doubted it was true. "Bill was one of the kindest people I ever met," Mitts says in a recent phone interview from his home in Grandview, Missouri.

When police interviewed Mitts after Bill's death, he told them he had visited the Prewitt house three weeks earlier. He also admitted he had shot Bill's semi-automatic rifle in the past. But he denied having an affair with Patty or that she had ever asked him to kill her husband.

A week later, Mitts says, he contacted police to tell them Patty had offered him $10,000 to kill Bill. "I had become a believer in Christ and [felt] convicted" about the need to tell the truth, he says.

But shortly after giving a statement to police, Mitts approached Patty and offered to divorce his wife and marry her. He thought that husbands could not legally be forced to testify against their wives.

"If I've ever wanted to commit murder, it was at that moment," Patty says during a prison interview.

Mitts says he was in love with Patty when he offered to marry her, even though he had just told police she wanted to kill her husband. "She was beautiful," he says. "I would have done anything for her but kill Bill."

Prosecutor Williams told jurors Patty finally grew tired of waiting for someone else to kill her husband and decided to do it herself.

"Her motive is clear," Williams argued. "Lust. Her fire burns hotter than most people's. And greed. With the insurance money, she would be free and independent."

Williams explained to the jury that the Prewitts were behind on Bill's life-insurance payments and that the grace period on both policies expired February 18, the day Bill was killed.

But when payments were missed, the whole-life policy remained in effect because the insurance company drew from the $14,000 in principal the Prewitts had already paid. The other policy would have been reinstated when the Prewitts made their monthly payment of $12. The two policies totaled $93,000. Patty testified that the couple's debts to banks, vendors and family members exceeded $170,000.

"Bill and I were civilized adults," Patty writes in a recent letter to the RFT. "We were not the kind of people who kill people for any reason. Divorce is the option civilized people use. Good Lord!"

Four days after Bill's death, officers used a magnet to recover the rifle from a pond 500 feet from the Prewitts' front door.

When deputies drained the mud and water from the pond, they found two footprints on the edge of the bank and another within one foot of the rifle. The prints matched the bottom of Patty's red rubber boots, which had been sitting outside the front door.

According to the state's theory, Patty ran through the thunderstorm to the pond and threw in the rifle. Williams argued that the gun stuck in the mud, "like a dart sticking straight up out of the water."

Williams said Patty waded into the water and pushed the rifle down. The shiny red boots were caked with an inch of mud when police presented them at a preliminary hearing.

But two of Patty's friends insist that's not the way the boots looked two days after the murder. Mary O'Roark Englert and Jerri Austin testified that they picked up the boots when they were at the Prewitt house to get clothes for Patty and the kids.

"They weren't spick-and-span, but they weren't muddy," Englert remembers in a recent interview at her home in Independence. "There was no way someone was walking around a pond in them."

In fact, Sheriff Norman testified that when he tried to walk through the pond, his boots mired down in the mud. Patty says after her attorneys had her buy a similar pair of boots and walk through the pond, the fleece inside was stained brown and ruined.

"Look at these boots," Bob Beaird, her defense attorney, told the jury. "Not one piece of mud on a shoestring, not one piece of mud in an eyelet, not one drop of muddy water inside of them. She doesn't walk on water."

According to testimony, the boots were eight inches tall. But Sheriff Norman testified the rifle was found on a sandbar in the middle of the pond in water that was eleven inches deep. The water closer to the bank, he said, was "deeper and very, very muddy."

Yet when deputies retrieved Patty's white flowery pajamas from her on the morning of the murder, there was no mud on them. When police cleaned out traps in the sinks and tubs of the Prewitt home, no mud was found there either.

Sarah and her eleven-year-old brother, Matthew, testified that they had been at the pond with their dad when it was frozen two weeks earlier. Sarah said she was wearing her mom's red boots, which she often did. "We were walking out [on the ice] and my foot fell through," Sarah told the jury. The defense theorized that is why the boot print was in the center of the pond.

Kansas City pathologist James Bridgens (who is now deceased) told the jury that Bill was shot twice at close range -- once in the temple and once in the back of the head -- making it "highly improbable" that the room was completely dark, as Patty described it. He also concluded that the shooter stood on Patty's side of the bed and would have been forced to lean over Patty as she slept.

The shot to the temple, Bridgens explained, would have rendered Bill unconscious but he could have continued breathing in a "rattly" manner -- the same word used by Patty to describe Bill's breathing.

The shot to the base of the skull, Bridgens testified, would have caused almost instant death. Prosecutor Williams argued that Patty would have been unable to describe Bill's "rattly" breathing because he would have been dead after the attacker left the room.

"By breathing, by clinging to his life, Bill Prewitt convicts that woman," Williams told the jury.

Juror Joy Cooper says she held out hope that Patty was innocent until hearing the pathologist's testimony. "It was very damaging," Cooper says today.

Though Patty's defense team did not call its own expert pathologist, the testimony of Bridgens has been questioned in other murder cases. In Cass County in 1988, three pathologists testified that a bullet that killed a woman was fired into her mouth, while Bridgens maintained she was shot by someone standing behind her. A medical examiner in Dade County, Florida, wrote that "Bridgens lacks credibility" in a 1985 murder case in which charges against the defendant were eventually dropped.

"I had stated that my husband was making gurgling noises," Patty wrote in an April 1993 letter to former Governor Mel Carnahan, asking for clemency. "Bridgens knew that so he testified that my husband would not have made any noises at all."

When deliberations began on Friday, April 19, 1985, seven jurors favored convicting Patty Prewitt while five maintained she was not guilty. "We all talked about what a bad job her attorney did," juror Joy Cooper recalls.

When the jury sent a message to the judge asking to declare a hung jury, he told them, "Try harder."

At twenty minutes till five o' clock, after deliberating for six hours, the jury foreman announced the guilty verdict. Patty's daughters recall that Bill Prewitt's family stood up and clapped.

Patty dropped her face into her hands and sobbed. Her kids started screaming. Many of the jurors also began weeping as her children's cries echoed in the halls outside the courtroom.

Before the trial began, Patty was offered and refused a plea bargain that would have made her eligible for parole after five years. "I said, 'I'm not leaving my kids for five years,'" Patty remembers.

Instead, the jury sentenced her to life in prison without the possibility of parole for 50 years.

Last month prosecutor Tom Williams spoke of the twenty-year-old crime and the trial he still remembers well. "In all my years of prosecution, I've never felt more secure in a conviction than I feel in this one," he says. "She was guilty as hell."

Still, juror Ronald Beaman, who now lives in Leavenworth, Kansas, says he felt the prosecutor went too far in trying to "portray her as a bad woman because of the affairs rather than just presenting the evidence of the actual crime."

Jennifer Merrigan, a law student at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, says Patty was convicted on the "slut theory." After Governor Bob Holden's office denied Patty's petition for clemency last October, Merrigan and staff attorneys at the Midwestern Innocence Project began investigating her case.

"A lot of times, especially when women are tried for violent crimes, the prosecutor puts on evidence of their loose moral fiber," Merrigan explains. "The jury convicts them basically for being a slut."

Juanita Stephens read about the guilty verdict in the Holden newspaper a week after the trial. The woman, who lived a mile from the Prewitts, contacted Patty to ask why she hadn't been called to testify.

That was the first time Patty or her lawyers ever heard about the strange car that Stephens said was parked a half-mile from the Prewitt home a few hours before the murder. Stephens said she made a special trip to tell Sheriff Norman about the white car, which she said was parked with its lights off atop a hill on a part of the road where the Prewitt house would be visible.

Stephens saw a man sitting inside the car at 12:15 a.m. as she returned home from town. She said the car later turned into her driveway, then backed out and headed in the direction of the Prewitt home.

At a hearing for a new trial, the sheriff (who is now deceased) testified that he didn't recall the conversation. He also said the Prewitt home would not have been visible from the road because of trees and hills. But the murder was in February when the trees were bare.

"Establishing that out on this country road, at the time of the crime, there was a strange car stopped nearby is extremely significant," says defense attorney Cardarella. "Had they revealed that information, there is no way on God's green earth that woman would have been convicted. And they knew that."

After the judge denied Patty's request for a new trial, her lawyers appealed and Patty remained free on bond. For a year, the family clung to hope. Then on a Friday night in late April of 1986, the phone rang. Patty's appeal had been denied. "They said they could come and get her at any point," remembers Jane, who now is 35.

That weekend, "Mom and all of us kids slept together and she gave all us girls a necklace and the boys St. Christopher medallions," Jane says in a trembling voice. "I can remember Mom and I hanging on to each other as tight as we could all night."

In the morning Patty's father came in the bedroom and said it was time to leave. "I couldn't let her go," Jane recalls.

On Monday morning Patty's parents drove their daughter to the county jail. The next day deputies loaded her into a patrol car, only to take her out again at the request of journalists who wanted to photograph her walking with her legs shackled.

"I will never forget that as long as I live," says Patty's mother, Ann Slaughter, "and I hate everyone that did that to her."

Patty was transported to the women's prison outside Jefferson City. In her journal, she wrote about being stripped, deloused and ordered to a holding area where her roommates included a biker heroin addict, a habitual hot-check writer and a chain-smoking killer who told stories about "the gruesome and senseless, Satanically inspired murder she had committed."

None of these women wanted to hear about "Suzy Homemaker and how she ended up in this Hellhole," Patty wrote in her prison journal.

Patty's children went to live with her parents on their ranch east of Lee's Summit. Sarah broke out in hives. The younger kids started wetting their beds again.

The first time they talked to their mom on the phone, after being separated for nearly a week, "they wailed and bawled so hard they barely make sense," Patty wrote. Even the prison guards were weeping when she hung up the phone.

Patty's parents brought the children to see her every month. In a trailer on the prison grounds, they could visit in a setting that felt a little like home. They all cooked together and played Trivial Pursuit and Simon Says.

On a visit in the summer of 1992, Morgan, her youngest son, prodded eighteen-year-old Matthew to show the muscles he'd earned working on a ranch all summer after graduating from high school. That was the last time Patty saw Matt alive.

He was found a week later, shot in the temple and wrapped in a blanket near his grandfather's ranch. Caleb Garrett, his best friend, says Matt had been depressed and drinking a lot. The night he died, he had been arrested for drunk driving.

That's when Matt told Glenn Hite, a former Johnson County sheriff's deputy, that he knew who killed his father. "He said he knew it wasn't his mother and he knew he was going to be dead soon," Hite says. "I told him to come back and talk to us when he was sober."

Matt bailed himself out and walked to Caleb's house, where he had been staying. Shortly after, he apparently shot himself with a revolver that belonged to Caleb's dad.

The family believes Matt may have been murdered. But his friend doesn't think so. "He said he knew things the other kids didn't know" about his dad's murder, Caleb says. "I believe he either saw it or he knew the person who did it. I believe that's why he killed himself."

Patty's daughters look at a family photo album at the home of Mary Longaker, Patty's sister. Sarah sits on the floor of Mary's spacious cabin with her legs outstretched and her one-year-old daughter asleep on her chest. Carrie Prewitt Melton, the youngest daughter, who was only eight when her dad died, wishes she could remember more about that night. Jane says it sometimes feels like they all are living in a nightmare.

A few years ago, Sarah built a Web site (www.patriciaprewitt.com) to tell her mother's story. The daughters theorize that perhaps their dad found out too much when he started investigating drug trafficking in the community as part of the PTA task force. Before Bill was killed, Patty says, he told her he was close to uncovering who was selling drugs in town. She says a notebook he kept in his shirt pocket was gone after the murder.

Jane says shortly after Matt's death, a man called her with an ominous message. "Everything is a sign," the caller told her. "Your brother is a sign."

It wasn't the first time Jane had received threatening calls. After Patty went to prison, someone called and said, "She better never tell anybody what happened. She better keep her mouth shut and rot in prison."

But Patty insists she does not know who killed Bill. "Would I stay in here eighteen years if I knew who did it?" she asks.

Patty, whose gray prison-uniform name tag has faded, is beaming on a recent morning at Vandalia. Her smile accentuates a few wrinkles, but her demeanor is more like a teenager than a 55-year-old grandmother.

As she begins telling a story about her family, she motions to the guard in the room and says in her friendly, country accent, "This is funny!"

He can't help but smile. And he's not the only one. Since coming to prison, Patty has won over inmates, guards, supervisors and even a friend of her sister who is now engaged to marry her.

"I always scoffed at prison romances," says Gary Kirkland, a 55-year-old musician who lives in Kansas City. "But it's just not possible that she did this."

Through tenacious letter writing, Patty has solicited the support of a dozen state legislators and even former President Jimmy Carter. In 2000, officials in Governor Mel Carnahan's office indicated they might commute Patty's sentence, making her eligible for parole. But the decision was nixed at the eleventh hour after Bill's sister, the prosecutor and Hughes, the former sheriff's deputy, objected.

Bill Prewitt's family declined to comment for this story.

But Hughes says Patty has everyone fooled. "[Patty Prewitt] is a potentially Academy Award-winning actress and a master manipulator."

Linda Walker, a former prison teacher, doubts it. Patty worked as a clerk for Walker for seven years and helped many women earn their general equivalency diplomas.

"I worked with her shoulder to shoulder and she's just a good woman," says Walker, who believes Patty is innocent. "She has a power, a spirit that is overwhelming."

The deadly saga of Patty and Bill Prewitt still evokes strong emotions in Holden.

"My personal feeling is she was guilty and I hope she stays there," says Sandy Carter as she flips a hamburger during the lunch rush at the Cowboy Inn bar and grill. "She wasn't really upset when it happened."

The town's treasurer, Sharon Manford, says she never believed Patty killed her husband. "I was around her too much," she says. "If she did, she sure got to me."

Kirk Powell, the former newspaper editor who covered the trial, says he's still undecided. "If I would have been on the jury, I wouldn't have voted to convict her. But I knew her. No matter what all the testimony and evidence showed, you still don't think someone you know is capable of that."

Retired Johnson County sheriff's deputy Glenn Hite believes the case should be revisited. Though he thinks Patty may have been involved, he doubts she pulled the trigger. "I think there are some more people who need to be behind bars," he says.

At the Holden newspaper, Pat Zvacek says she vividly remembers the cold and windy morning when she heard that Bill Prewitt had been murdered.

"Bill Prewitt was the kindest, most gentlest man I've ever known," she says. "None of us really knows if Patty did it. Only she knows."

1986 Pettis County murder trial of Patty Prewitt to air on NBCUniversal’s Oxygen Network

The book “Practice to Deceive,” by late Johnson County Prosecutor Tom R. Williams and Nan Cocke, highlights the 1986 capital murder trial of Patty Prewitt. The four-day trial at the Pettis County Courthouse was presided over by former Pettis County Presiding Judge Donald Barnes. The crime will be highlighted in an upcoming episode of NBCUniversal’s Oxygen Network documentary “Final Appeal.”

Photo by Faith Bemiss | Democrat

A classic who-done-it, a capital murder trial that took place in Pettis County will be highlighted in an upcoming episode of NBCUniversal’s Oxygen Network documentary “Final Appeal.”

The NBC Peacock Productions episode shines a light on the 1986 trial of Patricia Ann Prewitt, which was presided over by former Pettis County Presiding Judge Donald Barnes.

Prewitt, a mother of five, was accused of killing her husband, Bill Prewitt, a Holden lumberyard owner. She was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without eligibility for probation or parole for 50 years. Prewitt, who cited an intruder killed her husband and tried to sexually assault her, still maintains her innocence.

The trial was brought from Johnson County to Pettis County through a change of venue. It lasted four days, Tuesday through Friday, and it took the jury six and half hours to reach a guilty verdict.

Prosecutor for the case was the late Tom R. Williams, who eventually wrote a more than 500-page book about the crime. The book, “Practice to Deceive,” written with Nan Cocke, was published in 2016 after Williams’s death.

Barnes said the book played a pivotal point in NBCUniversal’s decision to air the episode and they in turn contacted him. Barnes and his wife Carol both read the large tome and noted that Williams’s account is accurate based on their knowledge.

Specifically, Mrs. Prewitt requests that the following items be tested for DNA:

2

(1) Pajama top of Patricia Prewitt (Item 18)1

(2) Pajama bottom of Patricia Prewitt (Item 19)

(3) Telephone and cord from master bedroom (Item 9)

(4) Telephone and cord from downstairs hallway (Item 13)

(5) “Veri Veri Sharp” serrated knife recovered from yard (Item 16)

(6) St. Regis Knife found behind cushion of love seat in family room (Item 1B)

(7) Paring knife (Item 3D)

(8) Brown towel (Item 6D)

(9) Cut & pulled victim hair samples (Item 20)

(10) Pillow and pillow case from under victim’s head (Item 3)

In the absence of eyewitnesses, the prosecution’s case relied heavily on attacks on Mrs. Prewitt’s character and credibility and the lack of an alternative suspect. DNA evidence corroborating Mrs. Prewitt’s account of an intruder who assaulted her and murdered her husband would create a reasonable probability that a jury would not have convicted Mrs. Prewitt. Mrs. Prewitt has served over 31 years of a life sentence; she has always maintained her innocence. Trusting that the Sheriff’s Office would find her husband’s killer, she cooperated with investigators

1 Item numbers are those indicated on the Property Records used the Johnson County Sherriff’s Office in their investigation. These records are attached as Exhibit A.

3

by meeting with them without a lawyer for over 20 hours in the three days following the murder. Trusting that a jury would reach the correct outcome, she rejected a plea deal that would have made her eligible for parole over two decades ago. Once again, Mrs. Prewitt places her trust in our justice system by petitioning this Court.

In support of her motion, Mrs. Prewitt pleads the following:

Sentence

A jury convicted Mrs. Prewitt of capital murder on April 19, 1985 (T. 707.2) She was sentenced to life without eligibility for parole until she has served fifty years (T. 710.) She is currently in the custody of the Missouri Department of Corrections at the Women’s Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center in Vandalia, Missouri.

Factual Background

High school sweethearts William (Bill) and Patricia (Patty) Prewitt married in 1968 (T. 572.) The Prewitts were active in their small community of Holden, a town with 2000 residents roughly fifty miles outside of Kansas City. By 1984, they had five school-aged children and owned and operated a lumberyard in the center of town. In the early morning hours of February 18, 1984, Patty and Bill returned to their home after a night of socializing with friends. Bill went to bed after

2 Cites to the Trial Transcript are cited as “T.” followed by the transcript page number.

4

checking on their children and Patty followed after placing some dishes in the kitchen sink (T. 602.) What happened next is, of course, the primary source of dispute in this case. Throughout the case, the prosecutor characterized Patty as a lustful woman intent on murdering her husband (T. 148, 656, 659, 664.) In his closing statement, the prosecutor reminded the jury that Bill Prewitt was “nude in that bed,” and argued that Patty, after “lulling an unsuspecting Bill Prewitt to sleep,” shot her husband twice (T. 659-60.) The prosecutor stated that Patty then “set the stage” to make it seem like an intruder murdered Bill and attacked her by inflicting marks on her throat, severing the phone line, and hiding the murder weapon (T. 660-61.) As described in greater detail below, Patty maintains that an intruder murdered her husband and attacked her before fleeing the scene. What is not disputed is that Bill Prewitt was shot in his bed and that Patty sustained injuries.

The Investigation

The lead investigator in the Prewitt case, Johnson County Deputy Sheriff Kevin Hughes arrived at the Prewitt home at about 4:40 AM on February 18 (T. 255.) Hughes conducted a brief survey of the murder scene. Mrs. Prewitt had driven herself and the children to the home of a neighbor, a former police officer, to seek help. (T.608-09.) Hughes drove to the neighbor’s home to interview Patty

5

with his colleague, Deputy Doug Rusher.3 Still dressed in the flower print pajamas she wore to bed, Patty shared her account with the investigators (T.274-77.) She told Hughes and Rusher that she woke up to what she thought was a clap of thunder.4 She was grabbed by her hair, and thrown to the floor by a man who pulled down Patty’s pajama bottoms and panties and held a knife to her throat (T. 277.) After a struggle, the assailant departed down the stairs.5 Patty checked on her husband who was incapacitated by the injuries he had sustained.6 The lights were inoperable, as were the phones.7 She gathered the children and left to seek help.8 Hughes learned from Patty that the Prewitts owned two guns.9 Patty had cuts on her neck.10 She did not receive medical attention for these wounds.

Subsequent actions by Hughes and his colleagues exhibit a single-minded focus on Patty as the perpetrator. As a result, no efforts were made to test evidence that could identify another suspect. Leads that pointed to another suspect were not followed. Indeed, Hughes later revealed he had arrived on the scene mindful of a

3 The account of this interview is drawn from the testimony of Kevin Hughes, where cited, as well as the report of the interview authored by Deputy Doug Rusher: Doug Rusher, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office, Offense/Incident Report, Complaint No. 84-085 (Feb. 18, 1984). This report is attached as Exhibit B.

4 Ex. B at 3.

5 Ex. B at 4.

6 Id.

7 Id.

8 Id.

9 Transcript of Deposition of Kevin Craig Hughes at 6, State v. Prewitt, No CV-584-84F (Mo. Cir. Ct. May 25, 1984).

10 Ex. B at 3.

6

statistic that seventy-five percent of murders are committed by a family member or friend of the victim (T. 328-29.) After his initial interview with Patty at her neighbor’s house, Hughes returned to the Prewitt home. Little physical evidence was collected in these crucial, early hours of the investigation, even though much could have been preserved. Fingerprints were not collected from anywhere in the bedroom or from the breaker box, which was the site where electric power to the house was cut (T. 316-17.) Reports made at the time by investigators do not note any effort to collect fingerprints or search for hairs in the bedroom (T. 327.) In fact, while Hughes described at trial a tepid effort to dust a few doorknobs, not a single fingerprint or hair sample was lifted from the entire house (T. 306-27.) In a report written over a year later, and just prior to trial, Hughes claimed that he had searched for hair to verify Patty’s account of being pulled from bed by her hair, but no quantities of hair were discovered.11 Contemporaneous records made at the time of the investigation do not support this assertion; no written records indicate that any such search was conducted (T. 325-27.) At trial, however, Hughes claimed that he saw hairs embedded in the bedroom carpet, but they appeared to have been there for a long period of time (T. 324.) Mary O’Roark, Patty’s friend and neighbor, cleaned the bedroom after the Sheriff’s Office released the crime scene.

11 Memorandum from Kevin Hughes to Tom Williams regarding Prewitt Crime Scene Search (undated, but at trial Hughes confirms that it was written the week before trial in April 1985 (T. 326.)), attached as Exhibit C.

7

O’Roark testified at trial that she had vacuumed hair off the bedroom floor (T. 551.) Some footprints at the scene were not analyzed despite later testimony from the sheriff at a preliminary hearing that many of these prints were present near the Prewitt home.12 The lack of thorough evidence collection at the crime scene is further demonstrated by the way in which a shell casing from the apparent murder weapon was discovered. Roughly eleven hours after the crime scene had been secured, a detective found it only because it fell out of a wicker loveseat that he sat on in the bedroom (T. 195-96.) The loveseat was just four feet from the bed where Bill was killed.

Instead of a thorough investigation of the crime scene, Hughes, in the early moments of the investigation, collected Bill Prewitt’s life insurance policy, which listed Patty, his wife, as the beneficiary, as well as over a dozen Alfred Hitchcock mystery novels. In a deposition three months later, Hughes stated that he had taken the books because “[o]n the back of one of the books there was an advertisement for another book, another novel of some kind that said something to the effect of how to commit the perfect murder.”13 It is noteworthy that the investigators looked to fictional material for answers while failing to collect concrete evidence at the

12 Transcript of Preliminary Hearing at 43, Missouri v. Prewitt, No. CR684-84F (Mo. Cir. Ct. Apr. 6, 1984).

13 Transcript of Deposition of Kevin Hughes at 17, State v. Prewitt, No. CV-584-84F (Mo. Cir. Ct. May 25, 1984).

8

crime scene. The focus on the mystery novels is indicative of the investigators’ tunnel vision and their related failure to preserve evidence of an intruder. With this bias so firmly in place, almost all of the leads and evidence pursued were those that seemed to confirm their foregone conclusion of Patty Prewitt’s guilt. These crucial decisions prevented Prewitt from the legal right of a presumption of innocence, a right that essentially disappeared as soon as the lead detective began his investigation.

Exculpatory evidence in the Prewitt case was ignored or explained away as immaterial. Ambiguous evidence was interpreted as confirmation of Patty’s guilt. Deputy Rusher conducted interviews with the Prewitt children on the first day of the investigation. Sarah Prewitt, age 12, and the oldest child present in the home at the time of the murder, described being awoken in her upstairs bedroom by her mother that morning.14 Her mother told her that there had been a fire and Sarah rushed downstairs.15 While Sarah was waiting at the foot of the stairs, she heard, according to Rusher’s record of the interview, a noise coming from the basement that sounded like rattling or someone banging on tin.16 Sarah also shared that she thought her dad was downstairs because she saw a light coming from beneath the

14 Doug Rusher, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office Supplementary Report, Complaint No. 84-085, Interview with Sarah Prewitt (Feb. 18, 1984), attached as Exhibit D.

15 Id.

16 Id.

9

basement door.17 Because power to the house had been cut, the light indicates that someone was in the basement with a flashlight. There is no record of any subsequent search of the basement as a result of Sarah’s comments. In his closing argument, the prosecutor dismissed Sarah’s account since it was given “after being in the custody of her mother,” implying, of course, that Patty had pressured her daughter to make the comment (T. 698.) Investigators likely dismissed Sarah’s account from the outset.

Additionally, a Prewitt neighbor, Ethel Juanita Stephens, testified in a hearing for a new trial that she spoke with the sheriff within a day or two after the murder to tell him that she had seen a suspicious vehicle on the desolate road facing the Prewitt home approximately two hours before the murder took place (T. 719-23.) There is no indication that the Sheriff’s Office conducted any investigation based on this information, nor was this information shared with the defense. The sheriff later stated that he did not recollect receiving such information, even though the investigative records include a lead related to a car on the road at the time of the murder (T. 732.)18 It is not clear if this lead is related to

17 Id.

18 Missouri Rural Crime Squad Complaint No. 84-085 Lead Assignment at 2, attached as Exhibit E.

10

Stephens’s report, but this lead was marked in investigators’ records as “void not issued.”19

On Sunday, February 19, the day after Bill Prewitt was murdered, Kevin Hughes convened the Rural Missouri Major Case Squad, as is common in rural counties with relatively small police forces. Approximately twenty-five officers from law enforcement offices across west central Missouri met for an initial briefing on the case from Johnson County Sheriff Charles Norman and from Hughes. In his handwritten notes of that initial meeting, the Officer in Charge of the Major Case Squad, Sheriff Paul Johnson noted “[t]he victim’s wife Patricia Ann Prewitt was a likely suspect[.]”20 The notes do not indicate discussion of other suspects at this critical investigative juncture. This meeting is described further in a personal memoir-style account of the case and trial authored by the prosecutor, first copyrighted in 1987 and published in 2016. According to the prosecutor’s account of this meeting, “Sheriff Norman wanted every fact considered on its own merit. Hughes had successfully set a different effort in motion. The facts would now be ‘reconciled’ to fit the Hughes theory. The investigation at that moment took a definite and direct course toward Patty Prewitt.”21 As a result, according to

19 Id.

20 Memorandum from Paul Johnson, Officer in Charge, Rural Mo. Major Case Squad (Feb. 19-22, 1984), attached as Exhibit F.

21 Tom R. Williams & Nan Cocke, PRACTICE TO DECEIVE 62 (2016

the prosecutor, “Hughes’s soldiers set out like a swarm of scandal sheet reporters, intent on digging up dirt.”22 At a time when critical physical evidence still remained uncollected and leads about an intruder uninvestigated, records indicate that the efforts of the Major Case Squad focused primarily on information about Patty’s extramarital affairs while she and Bill had been separated, and Bill’s life insurance coverage. Officers conducted numerous interviews to discuss second or third-hand accounts of Patty’s past affairs.23 By that Sunday, at least five individuals shared rumors that Patty had boyfriends and/or was a flirt in response to investigators’ questions.24 Such single-minded fixation on Patty and rumors of years-old affairs deterred law enforcement from following leads that would identify an alternative suspect.

Three days after the murder, on February 21, as critical latent fingerprint evidence sat uncollected from both the house and the basement, investigators recovered a gun believed to be owned by the Prewitts from a pond on their

22 Id. at 90.

23 Memorandum from T. Charrette and D.S. Stewart, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 10, Suzan Brown interview notes); Memorandum from Jefferson and Carroll, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 7, Billy Gunn interview notes); Memorandum from Jefferson and Carroll, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 23, Harmon Randolph interview notes); Memorandum from Frank Walker and Robert Scott, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 11, Paul Martin Kluz interview notes); Memorandum from Sammy L. Watson and Tony Zink, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 8, Robert G. Wolfe interview notes), attached as Exhibit G.

24 Id.

12

property and discovered footprints nearby that allegedly matched Patty’s boots. The prints cannot be placed within any timeframe related to the death of Mr. Prewitt, nor is it unusual to find a person’s footprints on their own property, but investigators were lost in the grip of tunnel vision. Patty was arrested on February 22.

The Trial

The State’s case relied on the absence of evidence of an intruder combined with attacks on Patty’s credibility. Of course, evidence that would exculpate Patty was not available at trial because investigators failed to collect it. In his closing, the prosecutor stated, “There’s not one shred of evidence, not one shred of evidence other than Mrs. Prewitt’s testimony that refutes [that Patty committed the murder]” (T. 661.) In effect, the prosecutor relied on the result of an inadequate and incomplete investigation to convict Patty. Because Patty did not retain a lawyer until after she was arrested, it was not possible for her attorney to conduct a defense investigation in the crucial early days after Bill’s murder.

The State repeatedly emphasized the absence of evidence of an intruder on the Prewitt property and mischaracterized the police investigation as including “a complete and through examination of the house from top to bottom [that] was conducted by the officers” (T. 134.) In his closing, the prosecutor cited the lack of vehicle tracks from an intruder’s car and the absence of shoeprints, other than

13

those the State alleged matched Patty’s boots where the alleged murder weapon was found, to demonstrate that Patty’s account was implausible (T. 661, 663.) By neglecting to preserve and recover evidence, the investigators in the case created a situation in which Mrs. Prewitt’s account could not be corroborated.

The defense’s theory of the case, besides no proof that Patty did this horrible crime, was that there had been an assailant in the house who committed the murder of Bill and the assault on Patty. Patty testified at the trial. She told the jury that Bill and her went out with their longtime friends for dinner and video games on the night of the murder (T. 600.) Patty and Bill returned home late and Bill went to bed after checking on the kids (T. 602.) Patty tidied up the kitchen and living room and then went to bed herself (T. 602.) She testified that she had awakened to what she initially thought was thunder (T. 603.) In darkness, an unknown assailant pulled her from her bed by her hair (T. 603, 623.) The intruder put a knife to her throat and attempted to rape her (T. 623-24.) He left the room and Patty then checked on Bill and realized he had been shot (T. 605.) She attempted to turn on the lights and to make a call for help but neither the electricity nor the phone worked (T. 351-52, 631.) Believing the assailant was still in the house, Patty collected the children (T. 605-06.) One of the Prewitt children, Sarah, testified that as she was leaving the house she heard a sound coming from basement and saw a moving flashlight coming from below basement door (T. 557.) A second Prewitt child, Carrie,

14

testified that she too had heard noises coming from the basement (T. 569.) Patty got the children out of the house and into a car (T. 607.) She then went back into the house to check on Bill (T.607.) Finding Bill dead, she went back to the children and drove to a neighbor’s house to seek help (T. 608.).

The prosecution’s response to Patty’s account of the evening was to attack her credibility based on her past extramarital affairs that had occurred over five years prior to Bill’s murder and during a time when Patty and Bill were estranged. During a trip to Sedalia in 1974, Patty was raped by three men (T. 582.) Following this traumatic event, Bill grew more distant from Patty, they slept in separate houses, and Patty began to see other men (T. 583-85.) By 1980, the Prewitts had reconciled and Patty did not have any additional extramarital relationships (T. 583, 593.) Nonetheless, the prosecution used Patty’s past affairs and insinuations about her promiscuity to move the jury.

Lead investigator Hughes described statements purportedly made by Patty while in custody for 16 hours two days after the murder. Hughes told the jury that Prewitt, in this unrecorded interview, said a number of provocative and sexually suggestive statements including that she had extramarital relations “at least once a day and sometimes three or four times a day,” that her “fire burns hotter than most people,” that she would not tell the truth unless caught red-handed (T. 297, 299.) Hughes claimed she asked him to take her out to dinner before she went to prison

15

(T. 300.) Patty has always denied making these statements. Missouri law now requires the recording of custodial interviews in such cases but, unfortunately, in 1984 such protections were not in place.

Patty’s neck wounds were dismissed as self-inflicted based on highly speculative testimony from a pathologist with a history of professional errors.25 Dr. James Bridgens, the second pathologist brought in by the State after the original pathologist failed to notice the second gunshot wound in the victim’s head, testified based only on his observation of a photograph of the wounds on Mrs. Prewitt’s neck, that they were characteristic of self-inflicted hesitation marks (T. 477.) The defense failed to call a forensic expert to counter Bridgens’s claim.

The State called Ricky Mitts, with whom Patty had a relationship six years earlier, to testify that Patty offered him $10,000 to murder Bill Prewitt in the summer of 1982 (T. 434-36.) Remarkably Mitts admitted in his testimony that after speaking to the police, he approached Patty and offered to marry her so he would not have to testify against her (T. 447.) Patty was repulsed by Mitts and found this suggestion outrageous and further evidence of how crazy Ricky Mitts was (T. 590.) In the prosecutor’s personal account, he wrote that Mitts was “in love with Patty, proficient with the murder weapon, and late for work on the morning of the

25 See, e.g., Bill Norton, A Difference of Opinion, Kansas City Star Magazine, Jan. 24, 1988, at 16-17, attached as Exhibit H.

16

murder; motive, means and opportunity—the classic formula. […] Couldn’t he have been, in fact, the intruder police never really looked for?”26 Despite what was so clear to the prosecutor, the investigators never pursued Mitts as a suspect.

In his closing, Prosecutor Tom Williams further attacked Patty’s character, arguing she “defiled [Bill’s] home with those lovers when the children were there” and “abandoned her duties as a mother” (T. 698.) “She disregarded her marital vows and the noticeable obligations of motherhood. She pursued one sleazy affair after another, one, two at a time” (T. 659.) He instructed the jury that “[t]he dignity of the institution of marriage” required a conviction (T. 701.) With that moral imperative given by the prosecutor, the jury was swayed and delivered a guilty verdict.

Argument

Mo. Rev. Stat. §547.035 provides, in pertinent part, that any person in the custody of the department of corrections claiming that forensic DNA testing will demonstrate the person’s innocence of the crime for which the person is in custody may file a postconviction motion in the sentencing court seeking such testing. Mo. Rev. Stat. §547.035.1. Such a motion must allege facts under oath demonstrating that:

(1) there is evidence upon which DNA testing can be conducted; and

26 Williams, supra note 21 at 401.

17

(2) the evidence was secured in relation to the crime; and

(3) the evidence was not previously tested because the technology for testing was not reasonably available to the movant at the time of trial; and

(4) identity was an issue in the trial; and

(5) a reasonable probability exists that the movant would not have been convicted if exculpatory results had been obtained through the requested DNA testing.

Mo. Stat. § 547.035(2).

The evidence submitted for testing in this case meets all of these requirements. Therefore, Prewitt is entitled to DNA testing.

1. There is evidence upon which DNA testing can be conducted.

All physical evidence mentioned above and referenced herein is believed to be available for testing. In or around April 2017, Johnson County Sherriff’s Office Lieutenant and Evidence Officer Andrew Gobber responded to a media inquiry by NBC Peacock Productions with a list of evidence currently held by the Sheriff’s Office.27

2. The evidence was secured in relation to the crime.

27 Letter from Lt. Andy Gobber, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office, to Derrick Loris, NBC Universal Peacock Productions, attached as Exhibit I.

18

All physical evidence mentioned above and referenced herein was recovered by then Johnson County Deputy Sheriff and lead investigator on the Prewitt case Kevin Hughes pursuant to the homicide investigation into the death of William Prewitt.

3. The evidence was not previously tested because the technology for testing was not reasonably available to the movant at the time of trial.

At the time of Mrs. Prewitt’s arrest in 1984 and trial in 1985, DNA analysis of physical evidence was not yet implemented in Missouri. Early forms of Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (“RFLP”) DNA testing did not become recognized and admissible in Missouri until 1991, see State v. Davis, 814 S.W.2d 593 (Mo.1991), and even that rudimentary form of testing was not reasonably available to defendants. While the now more commonly used Short-Tandem Repeat (“STR”) DNA tests were developed in 1996 and 1997, even those early forms of STR testing were not readily available in that time frame. See e.g., John Butler, Fundamentals of Forensic DNA Typing 70 (2009) (“As in the O.J. Simpson case[], conventional RFLP markers were used to match the sample of President Clinton’s blood to the semen stain on Monica Lewinsky’s dress. At the time these samples were analyzed in the FBI Laboratory (early August 1998), STR typing methods were being validated but were not yet in routine use within the FBI’s DNA Analysis Unit.”) (emphasis added). Indeed, authoritative sources, including the

19

leading federal commission on DNA testing, indicate that STR testing was not useful or even relied upon until well after that time. In 1998, United States Attorney General Janet Reno requested that the National Institute of Justice establish a National Commission on the Future of DNA Evidence to recommend ways that DNA technology could be used to enhance justice in the postconviction appeals process. US. Dept. of Justice, National Commission on the Future of DNA Evidence, Postconviction DNA Testing: Recommendations for Handling Requests, iii and v (1999). The Commission recounted the history of DNA technology up to that point, and confirms that STR testing was not reasonably available at the time of Mrs. Prewitt’s trial. The study reported in 1999 that in “in the near future, DNA testing at a number of STR locations will likely replace RFLP [Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism] and earlier PCR [Polymerase Chain Reaction]-based tests in most laboratories throughout the United States and the world.” Id. at 28. RFLP testing generally requires a DNA sample that is not degraded (and broken into smaller fragments), from 100,000 or more cells (e. g. a dime sized or larger saturated blood-stain). Id. at 26.

Modern STR testing utilizes 13 core loci (or genetic locations) that can be loaded into the DNA database. See FBI, Codis Brochure, available at http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/lab/biometric-analysis/codis/codis_brochure. Use of the 13 core loci allows for greater power of discrimination (ability to identify an

20

individual), far greater than earlier STR technology. Id. Earlier STR technology included just three loci, which results in match probabilities millions of times less discriminating than modern STRs (which use at a minimum the 13 core loci, plus up to an additional three loci.)

This important development is clear from the timeline provided by John M. Butler in his seminal text, Fundamentals of Forensic DNA Typing (2010). A well-respected scientist by both prosecutors and defense alike, Butler provides a timeline of DNA development which indicates that the CODIS database was not launched until 1998, which required tests to be performed at 13, rather than 3 or 4 loci. Id. at 9, available at http://www.denverda.org/DNA_Documents/Overview.pdf. In fact, the 13 loci were not even identified until 1997, and the tests which included fewer loci were not terminated until 1999. Id. As a result, it was impossible for Mrs. Prewitt to have requested testing at the time of her trial in 1985—the 13 loci profiles to be uploaded to CODIS was available, at earliest, in 1997.

With regard to the pajamas, telephone cord, and knife, the sensitive form of PCR STR testing was also not available at the time of Mrs. Prewitt’s trial. While modern STR testing might produce probative results, additional, more advanced techniques might also be needed, such as modern, advanced STR technology powerful enough to obtain a profile from “Touch DNA.” Touch-DNA generally

21

refers to skin cells left behind on an item. Touch-DNA was famously used in 2008 to exclude the Ramsey family in the death of their daughter, JonBenet. ABC News and USA Today reported on September 22, 2008, that “[t]he success of the little-known method in her case is triggering requests for the test from law enforcement officials seeking similar breakthroughs in unsolved crimes. Private and state-run laboratories report increases of up to 20% in use of the technique called ‘touch’ DNA.” Kevin Johnson, ‘Touch’ DNA Offers Hope in Cold Investigations, USA TODAY, September 22, 2008, available at https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/tech/science/2008-09-22-touchdna_N.htm. An article published by the Rocky Mountain News on July 9, 2008, reports that Touch-DNA technology was “new to the United States, though well established in Europe.” Todd Hartman & Lisa Ryckman, New to U.S., ‘Touch DNA’ Also Exonerated Masters, July 9, 2008. These news sources indicate that many law enforcement agencies, let alone defendants like Mrs. Prewitt, were not yet familiar with the capability of this new technology as late as 2008, and certainly not in 1985.

4. Identity was an issue at trial.

Prewitt has always maintained that she is innocent and that an unknown perpetrator committed the crime for which she has been convicted. (T. 603.) Therefore, identity was clearly an issue at trial, as required by § 547.035.2(4). See State v. Ruff, 256 S.W.3d 55, 57 (Mo. 2008) (“The phrase ‘identity at issue’

22

encompasses “mistaken identity,” but it also includes all cases in which the defendant claims that he did not commit the acts alleged…”).

5. A reasonable probability exists that Prewitt would not have been convicted if exculpatory results had been obtained through DNA testing.

Through DNA testing on Mrs. Prewitt’s clothing and a few other items from the scene, a third-party DNA profile could be developed. Because the state repeatedly attacked Prewitt's account of an intruder, presence of a foreign DNA profile on these items proximate to the murder would corroborate Mrs. Prewitt’s account and exculpate her. The profile of an unknown male developed on the pajamas, phone and cord, and knives would corroborate Patty’s account of the events on the night of the murder. It would also restore Patty’s credibility in the mind of the jury after being vigorously and unfairly attacked during the State’s case. Given the State’s emphasis on the lack of corroboration of Mrs. Prewitt’s account of an intruder, there is a reasonable probability that a jury would not have convicted her if exculpatory DNA evidence was offered to show a third party present in the Prewitt home. Additionally, if DNA from the physical evidence secured in relation to the crime were to match a profile in the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) national database or the state database, DNA testing could prove Mrs. Prewitt’s innocence and identify the actual perpetrator.

23

i. A DNA profile developed from Prewitt’s pajamas or the foreign hairs discovered on the pajamas could provide exculpating evidence.

Mrs. Prewitt testified that the intruder attempted to rape her (T. 624.) In his closing, the prosecutor dismissed Prewitt’s account as incredible (T. 659.) The prosecutor went on to say that “there’s not one shred of evidence, not one shred of evidence before you other than Mrs. Prewitt’s testimony that refutes” the prosecution’s theory that Patty lied about the intruder and murdered Bill (T. 661.) If Patty’s pajamas contain a third party’s DNA, either through touch DNA, ejaculate, or the foreign hairs, this would certainly be evidence to corroborate Patty’s account and bolster her credibility.

ii. A DNA profile developed from the telephone and telephone cords could provide exculpating evidence.

In his closing, the prosecutor told that jury that Patty cut the cord on the phone line (T. 660.) The DNA profile of an unknown male would corroborate Patty’s account and prove that an intruder entered the Prewitt home that night.

iii. A DNA profile developed from the knives collected could provide exculpating evidence.

In his closing, the prosecutor told the jury that Patty inflicted the hesitation marks on her throat (T. 660.) In his testimony, Dr. James Bridgens describes Patty’s wounds as characteristic of self-inflicted hesitation

24

wounds, not consistent with wounds to be expected from an attempted rapist wielding a knife in total darkness (T. 477.) The knives recovered from the crime scene may have DNA from the intruder and prove that Patty did not wield the knife on herself.

iv. A DNA profile developed from the dirty brown towel could provide exculpating evidence.

According to investigators’ records, the brown towel was found near the pond where the murder weapon was recovered.28 If the assailant used the towel, it could contain DNA evidence that would corroborate Patty’s account of being attacked.

v. Favorable DNA results would be sufficient to overcome the evidence presented by the State at trial.

Any exculpatory result from DNA testing would be sufficient to cast substantial doubt on the State’s evidence at trial and would provide a reasonable probability that a jury would not have convicted Patty if such corroborating results were presented during trial. Indeed, if testing on multiple items of evidence indicated a single unknown male source, a jury would logically have concluded that Patty was telling the truth about Bill being murdered by an intruder.

28 Ex. A at 4.

25

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, counsel for Patty Prewitt respectfully moves this Court to:

1. Compel the State to show cause as to why DNA testing should not occur pursuant to Mo. Stat. § 547.035;

2. Order DNA testing of the items set forth above;

3. Order that DNA profiles obtained from the above listed items be uploaded into CODIS;

4. In the alternative, order a hearing regarding why DNA testing should occur pursuant to Mo. Stat. § 547.035.

Respectfully Submitted,

/s/ Tricia J. Bushnell

Tricia J. Bushnell, #66818

Midwest Innocence Project

3619 Broadway Blvd., Suite 2

Kansas City, MO 64111

(816) 221-2166

(888) 446-3287 [Facsimile]

tbushnell@themip.org

Brian Reichart*

91 Manomet Ave.

Hull, MA 02045

(312) 375-9247

bsr22@law.georgetown.edu

* Pro Hac Vice Pending

26

CERTIFICATE REGARDING SERVICE

I hereby certify that a true and correct copy of this motion filed in the Circuit Court of Pettis County, Missouri, Division One will be sent via Post to Robert W. Russell, Prosecuting Attorney, Johnson County Justice Center, 101 W. Market St., Warrensburg, MO 64093 on November 27, 2017.

/s/ Tricia J. Bushnell

Tricia J. Bushnell

Exhibit List

Exhibit A: Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Department Property Records, Case No. 84-085 (Feb 18-21, 1984)

Exhibit B: Doug Rusher, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office, Offense/Incident Report, Complaint No. 84-085 (Feb. 18, 1984)

Exhibit C: Memorandum from Kevin Hughes to Tom Williams regarding Prewitt Crime Scene Search (Undated)

Exhibit D: Doug Rusher, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office Supplementary Report, Complaint No. 84-085, Interview with Sarah Prewitt (Feb. 18, 1984)

Exhibit E: Missouri Rural Crime Squad Complaint No. 84-085 Lead Assignment at 2.

Exhibit F: Memorandum from Paul Johnson, Officer in Charge, Rural Mo. Major Case Squad (Feb. 19-22, 1984), attached as Exhibit F.

Exhibit G: Memorandum from T. Charrette and D.S. Stewart, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 10, Suzan Brown interview notes); Memorandum from Jefferson and Carroll, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 7, Billy Gunn interview notes); Memorandum from Jefferson and Carroll, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 23, Harmon Randolph interview notes); Memorandum from Frank Walker and Robert Scott, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 11, Paul Martin Kluz interview notes); Memorandum from Sammy L. Watson and Tony Zink, Sheriffs, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office (Feb. 19, 1984) (lead number 8, Robert G. Wolfe interview notes)

Exhibit H: Bill Norton, A Difference of Opinion, Kansas City Star Magazine, Jan. 24, 1988.

Exhibit I: Letter from Lt. Andy Gobber, Johnson Cty. Sheriff’s Office, to Derrick Loris, NBC Universal Peacock Productions.

Here is an article written by her orginal attorney who is now a retired judge.....

Posted on Sun, Dec. 01, 2013 Patty Prewitt, convicted of murdering her husband, should be granted clemency

By ROBERT BEAIRD

Special to The Star

Special to The Star

The recent decision by the Missouri Court of Appeals vacating Ryan Ferguson’s murder conviction reminds us that our criminal justice system is not perfect. As a prosecutor, defense lawyer and a recently retired judge, I have seen our system from all sides and can attest to its strengths — and its shortcomings.