Benjamin Grover Brings His Family to Warrensburg

Benjamin Grover was a native of Xenia, Ohio where his father was a clerk of the circuit court. Born October 27, 1811, he moved to Madison, Indiana at the age of 23. While a resident of Madison, Grover was a business partner of Maj. John Sheets who ran a dry goods store and a paper mill. A romance soon developed between the young clerk and his partner's eighteen-year-old daughter, Letitia.

Letitia Downing Sheets was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, October 8, 1816. Her mother's maiden name was Anne Gardner. Letitia spent her early life in Madison, Indiana, to which place her father moved when she was six months old. She was educated in a private school in Madison, and on September 30, 1834 married Benjamin Grover. They made their home in and near Madison.

They welcomed their first child, John Sheets Grover February 13th, 1836. Something very interesting happened in St. Louis that same year. A railroad convention in that city appointed a committee to negotiate with congress for grants of land to aid proposed railroads. Benjamin Grover followed this news with great interest but did nothing at that time. He was a young man and the future of the railroad wasn't certain.

Sarah L. Grover was born at Madison on June 21, 1838.

Grover, became a Mason like his father-in-law who was once a Grand Master and was raised to the sublime degree in the Union Lodge #2 in Madison on October 16, 1838. The Grovers moved to Wirt, Indiana where Courtland Cushing Grover was born August 22, 1840. Then they moved back to Madison.

George S. Grover was the last of their children to be born in Madison in 1842. Before the year was over, the family moved to Missouri spending two years in St. Louis. In 1844, they moved to Warrensburg. Benjamin was at first engaged in the mercantile business in the little town and was a great success.

By May of the following year, the family bought a 320 acre farm from Martin Warren, the town's blacksmith. Martin Warren and family never lived on the farm that he sold to the Grovers. The William Gilkeson family was occupying the house as tenants when the Grovers purchased it.. The entrance to the acreage was where the intersection of Holden and Gay Street are now. A large gate, made to swing open at the center, hung between two large hickory trees. The road to the farm house began at this point. The acreage included some pasture land east of town that would, more than a century later, become known as Grover Park.

In 1844, the county road northward was on North Main Street turning west and continuing northward to Lexington. There were no streets east of Warren running north and south, and Gay Street was part of a county road that ran east to the gate of the Grover farm.

From that point, it turned north one block, to what is now East North Street, and continued east-ward to Georgetown, then the Pettis county seat. In other words, the road turned north to go around the Grover farm. The farm extended from what is now the middle of North Holden Street east to what is now Grover Park and from the middle of North Street, all the way to South Street.

Later, when Gay Street was extended though the Grover farm, Benjamin Grover would not allow it to be platted as originally intended because the street as planned would run straight through his home. Even today the street runs at an angle.

East of Warren street was a beautiful woodland extending east as far as what is now the corner of East Gay and North College and south and north several miles. East of North College about a half a block, a corner of wild prairie land came in and extended southward and eastward several miles.

The farm was surrounded by a rail fence "stake and ridered." The rail fence was built up to the usual height and then two stakes put in at the corners and crossed at the top. Then an additional rail was laid over the crossed stakes, the "rider." Missouri had no stock laws then so pastures and cultivated fields were fenced and stock could run out on the range or spaces not fenced.

The farm house stood a little west and south of what is now Lot No.One, Grover addition to Warrensburg, on the northeast corner of East Gay, and North College Streets (where the post office is now.). The log house was larger than what was usually built in the country back then.

It had two connecting rooms, each twenty feet square on the ground floor, and a hall, one room and attic upstairs. The house faced the east and had two immense outside chimneys, one of stone on the south and of brick on the north. Each held nearly a half cord of wood.

The kitchen, also twenty feet square was west of the north room of the house, detached about twenty feet. It had a brick chimney outside on the west and also a large fireplace. There were various cooking vessels for use at the fireplace, iron pots, iron ovens, standing on three or four legs, with iron lids. Bread was often baked in the iron ovens, such as batter for cornbread, biscuits, rolls, and light bread. The coals from the fireplace were drawn out under the legs of the oven, the lid put on, and more coals put on top of the lid.

Hams, shoulders, and large pieces of beef were always baked or roasted, slices of ham, beefsteak, spring chickens, quail, and prairie chickens were broiled on the grid iron on the stove hearth. No fried meat was used except sausage, and bacon, or chickens. Potatoes were roasted in the hot ashes, at the fireplace, and also green corn in the husk (hence the "roasting ear"). The old-time cooking was difficult, but very wholesome and appetizing.

It was the custom in all slave states to have the kitchen detached some distance from the main part of the house. All meals were cooked in the kitchen, but served in the other part of the house, hence the custom of detached kitchens was an inconvenience in stormy weather.

The new owner boarded up the space between the north room of the house and the kitchen with native lumber. The new room had a window and a door each north and south. This room was called "The Passage" and was used for a dining room in summer and a store room in winter. Above was a loft, also used for storage. A porch was added on the west side of the south room opening also into the passage. A frame shed was built on the north side of the kitchen with a flue on the west side. A large iron kettle was set in brick masonry like a forge. This shed was used for various kinds of farm work, such as preparing meat for curing, rendering lard, making sausage, and other necessary heavy work. The shed was enclosed on the north but open on the east side. A smokehouse stood in the back yard, where a fire of hickory chips finished off the hams, shoulders and side meat, to remarkable perfection. Beef was dried, or pickled, as "corned beef" for summer consumption. An ash hopper was erected where lye was made of wood ashes and rainwater"' and in due time, a supply of lye soap was made for the year's use. Wool was carded and spun, a handloom made the rag carpets and some kinds of coarse cloth. Various kinds of bread were made in the kitchen. All laundry was done at home.

One of the principle industries was that of candle making. The candle molds at the farm held two dozen candles. The twisted cotton wicks were adjusted to the proper length in the molds, and the molds set aside to cool. A tallow candle cut in two was placed in the lanterns. The tallow candle was never a noted success. It melted too rapidly and gave a very dim light. Sperm candles could sometimes be bought. They were of much firmer quality, and lasted much longer. The Grovers brought the first oil lamp to Warrensburg, a sperm lamp with a wick and an open bowl.

The Grover family decided to name their new place The Woodside Farm One of the Grover daughters, Elizabeth, later recounted, "The farm house, like other houses in the country at that time was seldom without guests. It gave shelter to many wayfaring men traveling through the country; the missionaries of the Presbyterian church, the circuit riders of the Methodist Church, and others. Previous to the time of the church's organization, the pioneer home missionaries of the church were accorded hospitable reception at the Grover home, and all possible aid was given them in their work. of evangelizing a new country. Such noted Presbyterian divines as Rev. Bradshaw and the great Methodist evangelist, Rev. Ashby made the Grover home their headquarters while in the vicinity. No weary or belated traveler was ever turned from its doors, and no compensation was ever asked or received."

Mr. Grover, while not a member of the Presbyterian Church, was a liberal and active supporter and furnished a great deal of the funds for the building of the first house of worship in the city and contributed largely to its support.

Letitia taught the children how to read and write while their father handled the arithmetic. He taught the multiplication table with a sheet of cardboard of his own designing. The Webster blue-back speller was considered old-fashioned so the Grover's used McGuffey's. Grover and Letitia were widely read and the farm home contained much of the best literature available at the time. Their father was a great lover of poetry and history and a man of fine literary tastes. On winter nights, Mr. Grover reread Walter Scott and the women sewed. On Sundays,the family attended religious services in the old courthouse. The children didn't spend all of their time indoors studying. Outside they learned to distinguish the various kinds of trees - wild plum, haw, cherry, oak, hickory and crab apple. They picked strawberries and walnuts, blackberries and hazel nuts.

Back in the 1840s and '50s, what would the Grover children have seen when they ran down the lane to the gate that separated their farm from the town. Once they were through the gate, they were at the end of Gay street. A quick run past the houses and up the steep hill would bring them to the business district on main street. Warrensburg was designated the county seat in 1835, so the courthouse and jail were already built on the hill. Wooden buildings housed their father's mercantile and other stores. Carpenters, stonemasons, and bricklayers were always busy building something new. It was a small town but was growing rapidly.

The Grovers Lose Two Children

They lost their oldest son two years after arriving in Warrensburg. Their family Bible recorded,

"John Sheets Grover died at Warrensburg, MO. on Saturday the seventh day of March A.D. 1846 at eleven o'clock a.m. - aged ten years and twenty-five mo, seven days.(He was born on the 13th of February 1836 so he died just after his 10th birthday. Whoever wrote, "aged ten years and twenty five mo." was really stressed out when they made this entry.)

Courtland Cushing Grover died at Warrensburg, Missouri on Monday Morning the twenty seventh day of April 1846 at a quarter before ten o'clock Aged four years eight months and five days.

(They lost two children in less than two months.)

Benjamin Grover and the Railroad

But life went on for the Grovers at a hectic pace. That same year, Benjamin organized the first Masonic Lodge in the county and helped lay the cornerstone for their building and Latitia, gave birth to a daughter, Annie Gardner Grover, November 14th, 1846.

In 1848, Benjamin was elected county sheriff, but he was rarely home. He spent much of the next two years traveling throughout the state, speaking in every county, stirring up interest in the public school system. He was an effective and forceful speaker who appealed to a wide variety of people. He was described by one Johnson County citizen as "a man of no ordinary ability. possessed of a wonderful memory. Although a Whig in politics, he could safely count on 200 Democratic votes in his support.

In 1850, Benjamin was elected Masonic grandmaster of Missouri As part of that responsibility, he devoted much time to the organization and building of the Masonic College at Lexington.

Through it all, his family at home kept growing, Their second daughter, Elizabeth Grover was born on May 27th, 1849 - the year of the famous gold rush in California. Because of that, people born in that year were often referred to as 49ers. The discovery of gold in California brought to the attention of the American people the need for rapid and dependable transportation to the west. Benjamin Grover had been thinking of this for years and he wanted Warrensburg included in this expansion.

Groundbreaking ceremonies for the start of the Pacific Railroad were held in St. Louis on the fourth of July 1851. The men and women of that young city turned out to watch the ceremony. The same year, another child, Benjamin W. Grover II, was born December 21st.. Two days later, the first five miles of Missouri Pacific track were completed in St. Louis. In that month, train service was established on that five miles, the first passenger service to operate in Missouri.

While Mrs. Grover had babies, Mr. Grover kept busy with other matters. His position as Sheriff was a springboard for him into higher office. In 1852, he started a term in the state senate representing Johnson and Lafayette counties. Amazingly, unlike modern candidates, Grover made only one campaign speech while running for senate.

Mr. Grover spent four years in the legislature, riding between Warrensburg and Jefferson City on horse-back carrying his two favorite pieces of legislation, one to reconstruct the public school system in order to place a good common school education within the reach of every child. The other to authorize the incorporation of companies for the purpose of constructing and operating railroads in Missouri. A bitter struggle was being waged in the state legislature.

On the table were two main proposals. The first, and probably the least expensive and most logical plan, was for the railroad to follow the Missouri River connecting prosperous river towns together like a trade route. The alternative plan, and the one strongly endorsed by Grover, was to bring the railroad inland through small villages and sparsely populated counties like Johnson. As the tracks advanced westward, Warrensburg needed a focused individual with a fiery spirit who could gain the attention of the powerful legislators who had the course of the railroad in the palm of their hands. Grover vehemently argued that the state had a responsibility to develop all areas of the state and not just the already wealthy towns on the river. It also helped that Grover was able to raise $100,000 in subscriptions (also called bribes) to help influence state representatives that Warrensburg owned the kind of wealth worthy of a railroad stop.

Also a shrewd business man, Grover had planned to make a lot of money because the plan to bring the railroad into Warrensburg was initially set to travel directly through his property with the depot resting nicely on his estate. With this, Grover could easily have sold off his land at inflated prices as the merchants of the community raced to place their businesses beside this monstrous attraction.

The road was almost completed to Jefferson City in 1855 when Warrensburg became an incorporated town. When Benjamin Grover's term in the Missouri State Senate ended in 1855, his friends presented him with a beautiful silver pitcher.cast from the metal of a hundred silver dollars which they had had made at Jaccards in St. Louis. The pitcher was presented in the courthouse, where the citizens had assembled.in the evening of February 3, 1856.

The chairman of the committee on the presentation was Mr. W.H. Anderson, the father of Dr. J. I. Anderson. Mr. Anderson said, "Mr. Grover, in the name and in behalf of the friends of internal improvement of the county, we present you this pitcher. We know of no better say to express our feelings toward you than to read the sentiment that we have engraved thereon, as follows:'Presented to Honorable Benjamin W. Grover by his fellow citizens of Johnson County, as a testimony of their affection for him as a man and particularly as evidence of their appreciation of the services zealously and judiciously rendered by him in the state senate and elsewhere in maintaining and advancing the interests of our county, and in inducing a healthy internal improvement system for the state at large. A. D. 1856.'

"Receive this token of our regard, sir, and place it in your family, and when you have passed away, and the iron horse snorts throughout town, bearing the produce of our rich soil and bringing in return therefore all the comforts and luxuries of life, when our country and our posterity are prosperous and happy, then your children with pride may point to that pitcher as an evidence that their father acted an important part in bringing about these results."

The honoree replied in a rather extensive address, "I receive sir, with no ordinary sensibility and with feelings of profound gratitude, the elegant gift, intended, as you assure me in a testimony of the approbation of my friends without distinction of party, for the course I have pursued, and the part I have acted, as their representative, upon an excited and vexed question, of public policy in our state Legislature.

Passage of the bill in congress demonstrates, beyond the possibility of doubt, that congress Intended the land to aid in the construction of those roads - and those only, to which the State had loaned her credit. When, however, the Legislature convened at that extraordinary session a general and widespread desire had manifested itself all over the state to enlarge our railroad system; indeed a railroad mania had seized the members of the Legislature, and each one had some favorite road, or roads to propose instead of carrying out the single and specific object for which the Governor had convened them.

"Under such circumstances, and in that peculiarly excited state of the public mind, a system of intrigue and management, I will not say of bargain and corruption, but I will say of logrolling commenced unparalleled in the history of the legislation of the legislation of any State in the union. Then it was a powerful combination of interests was formed both in the northeast and southwest portions of the state-backed by a majority of the Board of Directors of the Pacific railroad, and the power and influence of the river tier of counties to apply the land, which I maintained was intended for the Pacific road to the construction of a southwest branch, and the final location of our road through the river tier of counties. After a long and exciting struggle through which I have no disposition to travel - a struggle full of sectional animosity and personal bitterness, the Legislature did apply the land to aid the construction of a southwestern branch; but the friends of an Inland location defeatured on of the objects of the conspiracy - one too, that had secured and banded together the members from the river counties, and that was the final location of the road, through the river tier of counties.

"With the easy and reliable access to market, at all seasons of the year, which this road when completed is destined to afford our citizens when under the magic influence of such an outlet, our own beautiful and almost boundless prairies, shall rejoice in the smile of universal cultivation and the road itself will be freighted with the limitless products of our industry then and not until then will the original projections of this great enterprise and those who have assisted in carrying it forward to completion receive the full measure of reward which they deserve for their patriotic labors.

"Suffer me, in conclusion, to tender through you, to the donors of this elegant and beautiful gift, my sincere acknowledgements, and to you individually my warmest thanks for the kind and flattering terms in which you have been pleased to present it."

For Benjamin Grover, though, this was no time to rest. The tracks had not made it to Warrensburg. It would be many years before they arrived and things could easily change if another man from another town made a more appealing plea before the railroad infrastructure was in place.

His time in the legislature was done, so he directed his attention to the railroad company itself, securing a position as one of the early directors of the Missouri Pacific Railroad. In furtherance of that enterprise, he devoted the remaining years of his life.

Three days after his friends presented him with a silver pitcher, Mrs. Grover gave him a baby daughter. Martha Clinton Grover, was born at home on Feb. 6, 1856.

In spite of Benjamin Grover's hard work, it wasn't the railroad that first connected Warrensburg with the outside world. In 1858, the Westport Stage Coach began to pass through the town everyday. Miss Lizzie Grover later wrote an article about it for the local paper.

On November 18, 1858, the same year the Stagecoach arrived, so did the Grover's last child, Robert Grover.

While Benjamin Grover kept a busy schedule, his family was able to enjoy some good times in Warrensburg. Elizabeth, his daughter, was the one who would later chronicle what home life was like in Warrensburg in the years just before the Civil War. She remembered that time on her father's estate as comfortable and pleasant.

She recalled a special but undated summer celebration, "The Sunday School teaching consisted of reading and committing verses of scripture to memory. The Bible verses were printed on blue cardboard, usually one chapter on one card, and then cut apart and one verse doled out to each child at a time. A contest was held just before the time for the picnic, and the one who could repeat the greatest number of verses was allowed the unusual distinction of carrying the Sunday School Banner from the church to the picnic grounds.

"The writer, a regular attendant of the Sunday School won the contest and marched bravely carrying the small banner at the head of the procession of small children the long distance from the church to the grove. One other source of happiness to the winner of the contest that day was the fact that her cousin, George Harrison, of New Albany, Indiana was to be the orator of the day. George Harrison was eighteen years old, a tall and slender blond, who had graduated with honor in his home town and was spending the summer in the Grover home.

"After he had read the Declaration of Independence and delivered the oration, the festivities of the day began, with a bountiful dinner spread on improvised table, and presided over by the mothers of the town assisted by the eldest daughter of each family."

In April of 1860 the eldest daughter of the Grover family, Sarah, married John M. Barret, a 22-year-old graduate of the Law School in Nashville, Tenn. They moved to Sedalia where he began his law practice.

Along about that time, the family's teenage son, George, started a preparatory college course in Warrensburg in a private school run by George Johnson, a graduate of William Jewel college. The young men of this school were ready for senior college when the Civil War began.

The Grovers Go to War

Grover's interest in the railroad may have influenced his determination to preserve Missouri's place in the union. Abraham Lincoln's candidacy for president was bankrolled by railroad barons who expected him to aggressively expand their network westward. Grover was not a slave-owner nor an abolitionists but he felt that the union had to be preserved. By 1861, the railroad had reached Sedalia. Missouri mustn't, it couldn't, leave the union and destroy the dream of completing the railroad now.

For an account of Benjamin Grover's early Civil War adventures see

By September of 1861 Benjamin Grover, had organized his own unit and was heavily involved in local fighting. Col. Grover was detailed with parts of five companies with about three hundred men in all, to accompany Col James A. Mulligan from Jefferson City to Lexington. These men fought Price's advance forming Mulligan's rear guard all the way from Georgetown via Warrensburg to Lexington a distance of sixty-five miles without rest or rations and without dismounting a man except those who were killed or wounded in the repeated and sharp engagements.

Col. Grover must have stopped for at least a short time in Warrensburg to see his wife Letitia, because his daughter recalls a strange order he gave her as his unit fought a rear-guard action against General Sterling Price's advancing Confederate army. "He told my mother to put us all in a carriage and come along, too. There were six of us children then but one sister was married and was living in Sedalia and our oldest brother George had joined the Union army so mother had to look after four children. We got to Lexington just before the battle started." Their trip to Lexington on Sept. 12 must have been miserable because an early morning downpour turned the Lexington road into a quagmire. As they crossed the Blackwater bridge just north of Warrensburg, Union forces burned it to delay Price's advance.

At Lexington 3,500 Federal Troops from various units were digging in behind 8-12 foot trenches on the Missouri River bluffs. When Mulligan fortified Lexington, he stationed the Twenty-seventh with the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Missouri and the First Illinois Calvary on the bluff overlooking the river. On the march, about one hundred men had been cut off from the command at Dunksburg and were dispersed so that less than two hundred of the Twenty-seventh actually participated in the battle which lasted from Sept. 12 to Sept. 20, 1861. Mulligan's force was ill-equipped for a siege. Water and supplies were limited and his men had left Jefferson City with only 40 rounds of ammunition per man. His artillery consisted of seven six-pound cannons and a pair of mortars.

Price's force advanced on the town and after some stiff initial resistance, besieged the Union garrison. Realizing the venerability of his foe, Price chose to play a waiting game.

Elizabeth remembers, "Father sent a carriage for us because he thought we'd be safer in the fort than in town. Just before we got to the fort we saw Sterling Price's rebels about to attack.

"Suddenly, without a shot being fired, the rebels retreated. We went on to the fort without knowing why the rebels had withdrawn. Later I found out. It seems that some of Col. Mulligan's soldiers were Irishmen from Chicago. Before they left Chicago, an organization of Irish women there gave the regiment a flag with a large green shamrock on it. The rebels who were ordered to attack the fort were Irish, too, and when they saw that shamrock, they refused to fight."

Price was content to open the match with periodic shelling and skirmishing punctuating times of quiet. At first Union soldiers had some freedom of movement. Elizabeth remembers that during an early lull in the siege, Grover was able to visit his family. According to Elizabeth, "I spent the nine days of the siege at Lexington, My father put us all on a boat and told the Captain to take us and the other women and children to St. Louis. But the captain was a secessionist and remained at anchor the entire time. Bullets whizzed by and once the window of our cabin was shot out."

However, conditions quickly deteriorated for Union forces. The Confederates completely surrounded them and cut them off from water. Water and food supplies quickly ran out and the stench from dead bodies and horse carcasses added to the men's miseries.

During the nine-day siege, Elizabeth's mother, Latitia, went daily with other loyal ladies to tend the wounded and alleviate their suffering. These women were not allowed to carry food or water to the Union soldiers,. Some of the women who elected to stay with their husbands during the siege were allowed to go down to the river in the evenings to drink but they were carefully watched to make sure they didn't dip the hems of their skirts in the water. General Price didn't want them to return with soggy skirts that they could wring out to provide a few drops of water for their thirsty husbands.

The decisive battle came on Sept. 20 when Price launched an innovative "back door" attack up the steep river bluff. His men rolled hemp bales in front of them as movable breastworks.

Then the most desperate hand-to-hand fighting between the little band of less than three thousand Union soldiers, and Price's army of more than twenty-thousand men. During the heavy fighting, Grover was struck in the upper thigh by a musket ball as he directed his men on the firing line, When Col. Grover fell in the thickest of the fight on that afternoon, he had been continuously on duty and in the battle for sixty consecutive hours during all of which not a morsel of food or a drop of water had passed his lips.

The battle was terminated at last by the capture of Mulligan and his men. According to Elizabeth, "After the fort surrendered, our boat was looted and we lost everything we owned except our family bible which a stewardess had hidden until the looters had gone."

After the battle, Latitia was among the first to make her way through rebel lines to have the wounded Union officers moved to homes in Lexington where they could be properly cared for. Her own husband, Col. Grover, was taken by steamboat to St. Louis, but he could not recover. He died a painful death on October 20, 1861 at the home of a friend. He was buried with honors in Bellefontaine Cemetery St. Louis in a coat given him by General Ulyses Grant - the same coat he had worn throughout the fateful battle.

Colonel James A. Mulligan wrote a letter to Letitia, "Your husband rendered me constant aid during the dark days of Lexington. I remember him with pride. No man did his duty more nobly. I will not forget him."

When his father was mortally wounded at the battle of Lexington, George obtained a discharge from the army in order to assist his widowed mother and support his younger brothers and sisters. After her husband's death in St. Louis, Letitia and George agreed that it was dangerous for the family to return to Warrensburg. The timeline is unclear about the family's whereabouts for the next four years. Their first stop was in Monticello, Illinois where they spent at least a year. Elizabeth remembers that she attended school there for the first time in her twelve years of life.

According to some sources, the rest of the family moved to Syracuse in 1862 or 63 for another three years. These sources mention "Syracuse" but fail to say which state. Syracuse, Missouri is a few miles east of Sedalia along the route of the Pacific Railway. Syracuse, Indiana is much further north and east and in a safer location. In either case, a widow with children ,in those days, relied on family ties and obligations. Someone was at one of those locations who had volunteered to keep her and help her out.

Wherever the rest of the family went, records reveal that George was back in Warrensburg by 1864, while the Civil war still raged. In spite of the danger, President Abraham Lincoln saw to it that the railroad kept expanding westward until it finally came to Warrensburg in that year. Without the Grover family in the city to protect their interests, the whistle stop ended up on the property of Major Nathaniel Holden, an old real estate rival to Grover. As a tribute to his father, George Grover was at the ceremony to raise the American flag when the depot first opened. Soon he found work there as the station agent.

For that first year, work was again stalled and Warrensburg was the end of the line. An average of six or eight carloads of merchandise daily was shipped to Warrensburg and 20 or 30 freight wagons were often seen at the same time crowding around the station to haul away lumber, farm tools, provisions and many other items of merchandise needed in the new country. They were transported to Clinton, Butler, Harrisonville, Nevada, Fort Scott, Montrose and many other towns. A daily stage line for passengers and express connected with Lexington, Clinton, and Kansas City. Because of all of the activity around the new depot, townspeople rushed to relocate their businesses from the old center of town on the hill along Main Street eastward to Holden Street.

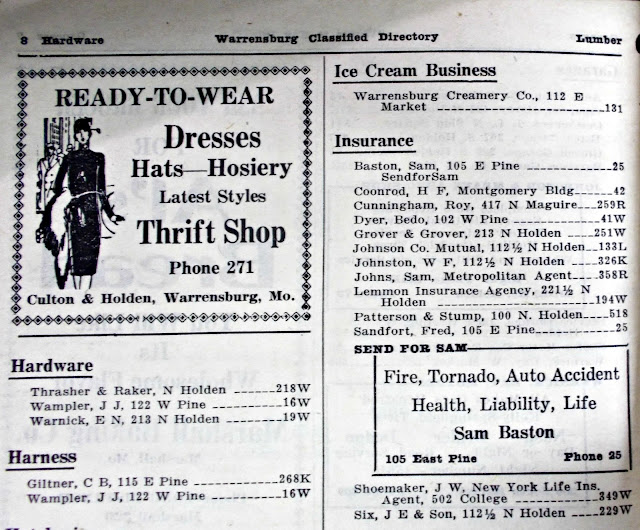

1867 advertisements as businesses relocate to be near the depot.

Early in 1864, rails, locomotives and cars had been taken by Missouri Pacific to Kansas City and construction started eastward from that point. George had become the captain of a volunteer company charged with defending the Missouri Pacific Railroad from Warrensburg westward and was involved in the battle of the Little Blue River which took place October 21, 1864 in Jackson County.

His father's old foe, Sterling Price had once again pushed northward from Arkansas. This time, his goal was only to capture Union supplies and outposts, hoping to negatively affect Abraham Lincoln's bid for reelection. Little Blue River was a one-day battle, part of a series of skirmishes that took place in the Independence, Missouri area.

Many things about this battle were reminiscent of the conflict that killed his father three years earlier. Union troops met Price in Lexington and were engaged in rear-guard action to slow his march westward. They were a force of 2,000 men led by Maj. Gen. James Blunt.

General James Blunt

General James Blunt

The Union force retreated westward and Price destroyed buildings, bridges and tracks from Franklin to Kansas City. Finally, Federal soldiers turned at the Little Blue River to make another stand using strong defensive positions on the west bank.

Maj. Gen. Samuel Curtis,

Maj. Gen. Samuel Curtis of the Kansas Militia ordered Blunt to turn back to Kansas City

Col. Thomas Moonlight

leaving only a token force under Col Thomas Moonlight. The following day, however, Curtis ordered Blunt to take all of his volunteers, including Capt. George Grover and return to the Little Blue.

As Blunt neared the stream, he discovered that Price's main force had already arrived and was fiercely engaging Moonlight's brigade, which was stubbornly guarding every available ford in the area.

Blunt quickly entered the fray, attempting to drive Price back beyond the defensive positions that he wished to reoccupy. A five-hour battle ensued as Union troops forced the Confederates to fall back at first, entrenching themselves behind several rock walls as they awaited a southern counterattack. Although witnesses reported that the hopelessly outnumbered Federals compelled their enemy to fight for every inch of ground, Confederate numerical superiority slowly took its toll. Gradually, the Northerners were forced to retreat, and the focus of the battle shifted to Independence itself. Although other battles were taking place in the same area at about the same time, there is no record of George Grover taking part in any of them.

At the same time George was fighting in western Missouri, his married sister, Sarah, moved to Pontiac, Illinois and sent for her sister Elizabeth, giving 15 year-old the opportunity to attend the excellent public schools there rather than move with the rest of her family to Syracuse. Elizabeth later recalled, "I studied there for two years and got a good enough education."

At the same time George was fighting in western Missouri, his married sister, Sarah, moved to Pontiac, Illinois and sent for her sister Elizabeth, giving 15 year-old the opportunity to attend the excellent public schools there rather than move with the rest of her family to Syracuse. Elizabeth later recalled, "I studied there for two years and got a good enough education."

By April of 1865 the confederacy collapsed and without resistance, the railroad in Missouri was extended on west from Warrensburg through Centerview, Holden and Kingsville. Other workers were building track from Kansas City to the east. On Sept. 19, 1865 the last spike was driven connecting the two parts of the railroad. Two days later the first passenger train completed a trip across the state leaving Kansas at 3:00 a.m. and arriving at St. Louis at 5 p.m. the same day. Now, in the unheard of time of fourteen hours, one could ride from one side of the state to the other.

Like his father, George had a strong determination to build for himself and his family a richer, fuller life. He was a wise man, wise enoough to realize, like his father before him, that education would be one of his community's soundest foundations..

He worked intelligently and, for the size of his task, quickly. He sold education to the public and to the state legislature. He spent countless hours on speaker's platforms and at conference tables.

By the close of the war in 1866, the first public schools opened in Warrensburg and the rest of the Grovers returned. Anna Grover found a job as a teacher; Miss Elizabeth filled in as a substitute for her sister Miss Anna.

George married Maggie Foster in 1866. She was Marsh and Emory Foster's sister

The Grovers brought Benjamin's body home to its final resting place in their plot in Sunset Hills.

Elizabeth lived in the family home with her mother, her younger brother, Robert, her unmarried sisters, Maggie and Anna, and most likely her younger brother Benjamin. The five of them lived in that home until 1868 when they had a new house of white pine built on their farm. Four of them would live out their lives together there. The post office's eastern parking lot occupies that space today..

George and Maggie's only child Bessie died in 1869. That was the year that Miss Elizabeth turned 20 and began teaching full time in Warrensburg. She would teach full-time from 1869 to 1882.making 16 years connected with the public schools.

The original Normal No. 2 was built in Warrensburg in 1872

When the first corner stone of the first Normal School building was laid in 1872, the Master of the Grand Masonic Lodge of Missouri, poured the wine on the corner stone from the pitcher his father had received for his work in bringing the railroad and education to Warrensburg.

The Grovers Begin to Wander

George served Johnson County as treasurer and collector for two terms from 1868 to 1872. At the end of his term, he moved to St. Louis, studied law, was admitted to the bar and entered the legal department of the Wabash railroad.

Of the three living Grover brothers in 1872, George was 30, Benjamin was 21, and Robert was 14.

There's not much record about the life of Benjamin Grover, Jr. in Johnson County. He was 15 when the family returned to Warrensburg in 1866 after a 4-year absence. There is no mention of him in the intervening years.

By 1876, his youngest brother, Robert turned 18 and enrolled in Normal #2 in Warrensburg. According to some sources he then headed off to commercial college in Kansas City. From business college in Kansas City, Robert went to Denver where he was engaged in journalistic work for two years. During his residence in Denver, he became a member of the Elks lodge.

Was Benjamin still in Warrensburg in 1879 when his sister Anna married Edgar Harris and went to live with him in Kansas City? Was he still in town in 1882 when his sister Elizabeth left the public schools and began teaching in Normal No. 2.

Benjamin was a bachelor then and over 30. He may have been roaming in the western states. The records just aren't clear until, according to the Grover family Bible, he married Sallie Cora Carpenter at San Francisco, Cal, on Tuesday, January 16th, 1883. He was 32.

In May of that same year, Benjamin's sister, Annie Grover Harris gave birth to her only child, Anne Gardner Harris in Kansas City, Mo. This little girl was destined to become the last of the Grover line to live (and die) in Warrensburg.

Meanwhile, Benjamin and Cora moved to Portland, Oregon when their first son, John Carpenter Grover, known as Jack, was born Nov. 22, 1883. About that same time, Benjamin's brother, Robert showed up in Oregon, too, where he worked several years as an auditor for the Northern Pacific Railroad during its period of construction.

In 1888, John Barrett, died at St. Paul, Minnesota of pneumonia. Sarah had traveled extensively in the 28 years she had been married to John. In 1867, they had left Pontiac, IL. and gone to New Orleans to where he worked as a reporter. For the rest of John Barrett's life, he was connected with the leading newspapers of the south and west. When he died, the St. Paul Daily globe ran this obituary.

"Col. Barrett was one of the best known newspaper men of the Pacific coast, and a gentleman of superior intelligence and rare ability. For many years he was connected with the New Orleans Picayune, and was at one time the Washington correspondent of that paper. About Seven years ago and assumed the editorial management of the Examiner and until about a year ago he retained a connection with that paper. He left San Francisco, n the early part of the summer to travel with his invalid wife. About two months ago he came to St. Paul, and finding the climate beneficial to Mrs. Barrett's health, he decided to remain during the autumn.

Being a man of industrious habits and fond of his profession, he accepted a position on the editorial board of the Globe and had been associated with the paper for the past month. When he went home from his office last Tuesday night he was complaining of a cold and a pain in his chest. Pneumonia set in the following day and he died last night at 9:30 p.m.

His wife, Sarah, brought him back to Warrensburg for Interment and the funeral was held at the home of Sarah's mother, Letitia Grover. Sarah may have chosen to stay in Warrensburg, Married women were expected to not work back then, so help from other family members was important to widows. They often went back to the family of their birth at times like those.

Letitia and the GAE

During the period from her return to Warrensburg in 1866 to her death, Letitia, busied herself with the Warrensburg chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic, This was a fraternal organization that helped disabled Union veterans and raised money to build monuments to fallen Union soldiers. The Union veterans in town so admired her husband that they named the local post after him. In 1887, when they decided to attend a national encampment in St. Louis, she presented the post with a banner. On Sept. 10, 1887, a few days before their departure for the encampment the Grand Army marched to her home on Gay Street where a large number of people had assembled to watch the presentation. Here Mrs. Grover, standing in the midst of her family and friends presented the beautiful banner to "our boys in blue." They cherished it for many years as "a token of love from a patriotic woman to the men who offered their lives on the alters of their country."

A ribbon worn by a member of the Col. Grover post at a reception during the St. Louis Convention

Robert, Benjamin's restless and wandering brother left Oregon and landed a job in 1889 as a deputy internal revenue collector in Dallas, Texas. Benjamin and Cora moved from Oregon to Denver and finally to El Paso, Texas where their second son, Benjamin III, was born March 22, 1893.

The Grovers Come Home

Back in Warrensburg, Elizabeth retired from teaching to stay at home with her mother and sister Mattie. Letitia's health began to decline and Robert came home to live with his mother and his sisters.

Benjamin continued to live in El Paso until he died in 1896 at the age of 42. Cora and her two sons brought her husband back to Warrensburg to bury him.

For the third time, Latitia stood at the graveside of one of her sons.

The Grover family convinced Cora to stay in Warrensburg. They would help her start a new life there. Cora's oldest son, Jack was 13 when his mother moved him to Warrensburg and the Grover family farm was long gone, divided into lots and streets. Benjamin III, the youngest son was only three years old. Cora found a residence on North Maguire Street and soon found students to come to her home for music lessons.

Cora was born in St. Louis, in 1856 and spent her girlhood there. She graduated from the Lindenwood college at St. Charles.and later graduated in music in St. Louis. She was devoted to music and for many years was regarded as one of Warrensburg's best singers and a most competent teacher. Jack attended high school where he took an active part in school sports. and later Central Missouri State Teacher's College.

Grover and Grover Real Estate - Robert and Elizabeth

While her sister-in-law kept busy teaching music, Elizabeth grew bored at home and decided in 1897 to open a real estate and insurance office with her brother, Robert. When the Grovers opened their office at the back of the second floor of the then most attractive office building in town, every room was filled with professional people. However, it was a time when few women adopted professional careers.

She later admitted, "My friends were shocked and had little confidence in my ability to make a successful business woman. I had taught twenty years in Warrensburg, in the public schools and the Normal and I decided I would like to enter the business world and I have never regretted it. The brother and sister partnership expanded to seven insurance agencies and Miss Lizzie became the town's leading real estate dealer for thirty years. She was described as energetic and thrifty, pleasant and with a personality that attracted many patrons.

Much of their real estate work included selling and renting plots of the Grover family farm as the town expanded eastward. A portion of undeveloped pasture land served as a playground for the children in that part of town.

Much of their real estate work included selling and renting plots of the Grover family farm as the town expanded eastward. A portion of undeveloped pasture land served as a playground for the children in that part of town.

The Grovers in the Twentieth Century

Letitia died in 1901. Her obituary described her thus, "A woman who was ever patriotic and loyal, and in whom the Union soldier always found a friend, both during and since the war, and whose loyalty to her country lasted until the day of her death. She was a friend of the poor. She was the friend of the slave. She was a pure hearted, unselfish woman who sorrowed with those who mourned, and was glad with those who were happy...

"Since the war, this noble woman's life has shone as a bright star of patriotism among the people who were her husband's friends and followers... Mrs. Grover died in the faith of the Presbyterian Church and she had been identified with the interests of the church in this city since its organization in 1852.

"Her funeral took place at her home and was attended by a large concourse of her old friends. Col. Grover Post attended in a body and her pall bearers were selected from among its members. Rev. J. M. Ross conducted services and spoke freely of the life work of the deceased. The funeral was then formed and took its way up to the city cemetery where all that was mortal of Mrs. Grover was laid beside her husband."

After he graduated from the Normal in 1903, Cora's son, Jack, went to Gallatin, Mo where he was principal of the high school At 19 he found himself teaching some young men his age or older. Jack would never return to Warrensburg to live, but he visited very often. The Standard Herald ran this piece in January of 1904.

"New Years day, Mrs. Cora Grover gave a daintily appointed one o'clock luncheon in honor of her son, Prof. John Grover, who was home from Gallatin for the holidays. The name cards were pictures of well known characters and formed pretty souvenirs of a happy occasion. Covers were laid for twelve."

Just a week after this visit, Sarah, was involved in a serious accident and died of her injuries a short time later, The Standard Herald ran this obituary,

Mrs. Barrett Dead.

Eldest Daughter of the Late Col B. Grover Dies at the Family Home in this City.

Mrs. Sarah L. Barrett died at the home of her brother and sister, Robert F. and Miss Lizzie F. Grover, at 9:40 o'clock Monday evening. The cause of Mrs. Barrett's death was a severe fall she sustained some two weeks ago, from which she never recovered. Since the accident, she has grown weaker by the day until Monday evening the final summons came. The funeral services were held at the family home Wednesday evening at 2:30 o'clock. Rev. Edward H. Galvin of the First Presbyterian Church officiating. The remains were then interred in the Grover lot in the cemetery beside those of her husband, John M. Barrett who died in 1880

Sarah L. Grover Barrett was born in Madison Indiana, June 21, 1838 then moved to Warrensburg with her parents in 1847. In 1860 the subject of this sketch was married to John M. Barrett. Three children blessed the union. Benj. W., who died in 1880, Gannie, Mrs James Y. Eccleston, who died at Oakland, California, nearly four years ago and George D. Barrett, who is now living on the north Pacific coast. Her loss is mourned by three sisters and two brothers.

In 1905, after teaching a few years in Gallatin, Cora's oldest son Jack, went to Washington University in St. Louis where he joined the track team and set the school record for the hundred yard dash and a world record for the 50 yard dash. He received his degree in 1908 and moved to Kansas City where he would live and practice law for the rest of his life..

Cora was only 52 when she died in 1908 in a hospital in Kansas City.

The news of Mrs. Cora Grover's death came as a great shock to friends and relatives. Her condition was known to be serious indeed but none expected death so soon. It was due to cirrhosis of the liver and though hopeful to the last, she was forced to succumb, so on Tuesday morning, January 21 in Kansas City, she fell asleep.

The funeral of Mrs. Cora Grover was held at her late residence on North Maguire street Thursday morning with Christian Scientists in charge. The remains were then conveyed to the city cemetery, the pallbearers being E. W. Cassingham. S. H. Coleman, John G. Stone, Frank L. Mayes, T. E. Cassingham and E E. Burchfield.

In 1908, three of Benjamin and Latitia's children were unmarried and still living at home. Robert and Elizabeth ran a real estate business and Mattie kept house for them. There is no mention who took Cora's youngest son, Benjamin, 14 at the time of his mother's death. Since he stayed in Warrensburg to graduate from high school and then college, it is probable that he lived with his uncle and aunts.

Their Kansas City niece, Annie Gardner Harris was about to graduate from the University of Kansas having received her bachelors and masters degrees there. She was going to go on to study at the National University in the City of Mexico, in Quebec, Canada, in the Universities of Missouri and Chicago. In 1912 she came to Warrensburg to live and teach at the State Normal #2 which members of her family had so long championed.

Annie's nephew Benjamin was a student at the Normal at that time. He graduated in 1914 and moved to Columbia to enter the law school of the university of Missouri.

Although Mattie was less active in business and politics than her siblings and niece, she had a keen interest in the affairs of the town. She was one of the many women in Warrensburg who signed a petition urging men to vote for temperance in 1914.

Lizzie Grover's name appears second from the top while Mattie Grover's name is second from the bottom.

Anna Gardner Harris added her name to the petition, too

This poster was signed by many citizens of Warrensburg in January 1914 showing their support of a local option election to continue the ban on the sale of alcoholic beverages The issue was temperance which was very popular prior to the passage of the 18th amendment in 1920. In 1910, the citizens of Warrensburg had voted to end the sale of alcoholic beverages by a margin of 164. The issue apparently had to be submitted to the voters every four years. Naturally the dry forces wanted to continue the ban. Thus, they organized and campaigned.

During the campaign there were many strategies used to convince the people of the evils of alcohol. The poster signed by those citizens who supported the ban was just one.. Another big demonstration in the campaign was a parade through Warrensburg on the Saturday before the election. With participants estimated at 1,500, the parade began at the courthouse square led by the Boy Scouts and Normal band. Included in the line of march were Pioneer Girls, public school children, Sunday schools, WTCU members, Normal students and other interested parties. While most walked, carrying banners with appropriate mottoes, some drove surreys, and others, automobiles, The final rally was held at the courthouse the evening before the election. It drew a crowd that spilled into the hallways of the courthouse.

Although the wets had not campaigned actively before the election, both sides were out in force before election day, the women of Warrensburg, who did not yet have the vote, were determined that the outcome of the election would not be influenced by the free use of booze and they stood guard along the streets and alleys all day.

The outcome of the Tuesday election favored those who had worked so hard to continue the ban on the sale of liquor. The local newspaper, the Weekly Standard, mentioned the work of the women in the campaign and election day patrol. "It is a sample of what would happen if women were given the right of franchise and that time is coming soon."

While we don't know if Mattie or Lizzie Grover took part in the parade or the election day vigil, it is certain that they were aware of and keenly interested in the activities. Mattie had joined the Presbyterian church at an early age and was active in that organization. If her Sunday School marched in the temperance parade, chances are good she was there.

One of the most memorable local events of the early 20th Century was the fire that destroyed the one building that was Normal #2. After the Normal School burned in 1916, the articles in the corner stone were taken out and displayed in one of the stores in town. The old silver pitcher that had been presented to Benjamin Grover was also shown in the window for one day. At that time, Robert was president of the Board of Regents and was influential in rebuilding the school.

With the entrance of this nation into World War I, Benjamin Grover III, then 24, enlisted and spent a few months at Ft. Sill. Later he entered the air service and spent a number of months at Kelly Field No. 2. San Antonio, Texas. The squadron was sent overseas and was encamped in England when the armistice came.

In 1919, he entered the practice of law in Kansas City where he spent the remainder of his life.

When women finally got the right to vote in 1920, Maggie's sister, Elizabeth, then in her 70s, became active in politics. Miss Lizzie was a great reader and and student of literature and was well informed on public questions. While she took great interest the political campaigns of both parties, she remained a partisan Republican. When Warrensburg residents realized the importance of having a woman member of the Board of Education, Lizzie Grover was named by the Republican party as its candidate. During her membership in the 1920s, the move for a new high school building was started and carried though and she was made a member of the building committee. Many of the conveniences n the building are due to her wise foresight.

Despite an injury she sustained in a fall in 1923 at the age of 75, she continued to climb long flight of stairs to her office every day. By 1924 the big hall was empty, but the closed doors and deserted rooms didn't bother Miss Grover for her own business kept her busy.

Meanwhile in St. Louis, their brother George died October 1, 1927.

His body was returned to Warrensburg. Funeral services for George Grover were held Wednesday, October 5 at the Sweeney-Gore-Phillips Chapel, conducted by the Rev. R. C. McAdie, pastor of the First Presbyterian church. Oct 4, 1927.

His death left only three of the Grover siblings alive.

The 1927 Warrensburg phone book lists Robert and Lizzie Grover as living at 203 East Gay. Although Mattie lived there too, she isn't mentioned. That is now the U.S. Post Office parking lot.

The same phone book shows an advertisement for their insurance business.

And a separate ad for their real estate business

Records show that Robert J. Grover deeded the remant of the Grover farm - that undeveloped pasture land that lay beside east Gay Street - to his nephew Jack on July 2, 1927. It is unclear whether either sister had a share or a say in that land.

When Robert wasn't busy with his real estate and insurance business, he devoted his time to the Republican Party, Although R.J. Grover was was interested and active in politics all of his adult life, his only political appointment in the state was as a supervisor of the 1930 census for the sixth district. He was known throughout the state as an influential member of the Republican County Committee and also served many years on the state committee.

Mattie stayed in the home in which she was raised devoting her life to keeping house for her family until she became too ill in 1931 to keep up her chores. She was virtually an invalid, too ill to even attend church. She had become a member of the Presbyterian church when quite young and was a regular attendant and devoted member until she became too sick to go. She died three years later in that home at 203 East Gay, in 1934 at the age of 77.

Her funeral was held at the family home Sunday afternoon, Jan 8, 1934 conducted by the Rev. J.C. Hollyman. pastor of the Presbyterian Church. "Safe in the Arms of Jesus," and "One Sweetly Solemn Thought" were sung by a quartet composed of Mrs. W. R. Hardey, Miss Elenor Shockey, Will Shockey, and Dr. A. L. Stevenson, accompanied by Mrs. W. L. Chaney. The pallbearers were Will Shockey, W.R. Hardey, Allen Gilbert. H.T. Clark. L.W. Hout and M. J. Christopher.

(Both sisters were interested in church work and active members of the Presbyterian denomination, but it was Miss Elizabeth who was for 41 years secretary of the church. )

Around the time that her aunt Mattie died, Annie Harris was chosen to lead the department of foreign languages at Central Missouri State College.

Robert, Benjamin and Letitia's youngest child, died on feb 12, 1936 at his home after an illness of about two weeks. Funeral services were held at the Presbyterian conducted by the Rev. J.C. Hollyman. Active pallbearers were Dr. L. J. Schofield, J. B. Christopher, W. E. Johnson, Jr., Dr. H. A. Phillips, A. G. Taubert, and L.E. Quick of Holden.

Honorary Pallbearers were John H. Wilson, F. W. Urban, Dr. W. E. Morrow, G. O. Rundle, Oscar Brock, A. T. King, T. A. Sollars, Dr. E L. Hendricks, John Thrallkill, G. E. Hoover, E. W. Cassingham, C. A. Kanoy, H. O. Davis, C. F. Martin, W. H. Russell, C. A. Calvird, Jr. of Clinton, T. J. Halsey of Holden, George S. Poage of Centerview.

Funeral services for Robert J. Grover were conducted Friday afternoon at the Presbyterian church by the pastor, the Rev. J. C. Hollyman. Music on the organ was by Mrs. Neal Glaspey. The Elks conducted their ritualistic burial service at the grave side with the Exalted Ruler S. C. McCann in charge.

The following notice was posted on the bulletin board at the College:

"Out of respect for Robert J. Grover, once president of our Board of Regents, all College activities will close during the funeral hour."

Elizabeth Grover

Of the nine Grover children, only Elizabeth was still alive. Although she was in her eighties she continued working. On her eighty-seventh birthday anniversary, Miss Lizzie walked to her office as usual, surprised when her friends who had gathered to celebrate her birthday exclaimed over what to her was mere routine. A reporter from the Star-Journal showed up to record the event.

Sometime in her 80s Miss Lizzy earned the title of Warrensburg's Oldest Native Born Citizen. She still lived on Gay Street in the house built and lived in by her mother, brothers and sister but now she was alone. After her brother's death, she spent considerable time with her niece, Miss Harris and as her health became more frail, the family home at the corner of east Gay Street and north College Avenue was sold and she lived with Miss Harris.

(John Grover was Benjamin and Cora's son. He came to Warrensburg from El Paso, Texas after his fathers death in 1893.)

(John Grover was Benjamin and Cora's son. He came to Warrensburg from El Paso, Texas after his fathers death in 1893.)

When the old house was sold at auction, John C. Grover, then a Kansas City lawyer went down to Warrensburg to look the house over. He found hundreds of books and old magazines, along with Civil War relics of unusual interest. Many of the articles were given to the Missouri Historical society but Mr. Grover kept an affidavit of non-residence in Abraham Lincoln's handwriting and with his signature. Mr. Grover also kept a pair of spurs captured from a Confederate. The rowels of the spurs were made from half dollars bearing the date of 1856.

Even though time had forced her to slow down, Miss Lizzie remained quite active. She became a writer and somewhat of a celebrity in town. Warrensburg was proud of the Grovers. A street was named for the family and on anniversaries of Civil War battles, J.L. Ferguson, local historian in the 1930s, wrote of the part played by Colonel Grover and young Captain Grover. Mr. Ferguson was a pupil of Miss Lizzie's.

Miss Lizzie wrote a book on the early days of Warrensburg which never was published. In the last two years of her life, she didn't get downtown often, but old friends dropped by and she was as keenly interested as ever in the town's goings-on.

For several years Miss Lizzie and the Warrensburg Star-Journal conducted an amiable argument on the subject of a picture of Miss Lizzie. The newspaper had no picture of her in its files and Miss Lizzie refused to be photographed. She said she had a picture taken when she was 30. She saw no reason to have another made.

By 1938, Elizabeth could no longer go to her office but she still considered herself to be actively engaged in business. In reality she depended on her associates to run things.

She finally had to admit that she could no longer work at all.

Miss Lizzie Grover quietly celebrated her ninetieth birthday Saturday at the home of her niece, Miss Anne G. Harris, where she lived her final three years. Many cards arrived for her and there were also several birthday cakes and other gifts.

Although her mind was as keen as ever, Miss Lizzie tired quickly and became bedfast for four months before her death She was keenly interested in the coming political campaign and enjoyed seeing her friends. Then one Sunday afternoon, she sank into a coma from which she was roused only for a short time.

The funeral was held at the Presbyterian Church conducted by the pastor, the reverend J.C. Hollyman and the Reverend E. H. Eckel. She was buried in Sunset Hills. Counted as one of Warrensburg's foremost citizens, Miss Grover stood equal to the men with whom she associated.in professional and business life for 72 years.

A woman of strong convictions, Miss Grover was never dogmatic or bigoted. She took great pride in her accomplishments and those of her family. Her wit was keen throughout her life and she was widely quoted by her friends for her ready replies potent with humor and revealing her deep insight into humanity. Her devotion to her sister, Miss Mattie, and to her brother, Robert who died Feb. 12, 1936 was a vital element in her life.

Miss Grover was the author of a series of articles of early Warrensburg history published in the Standard Herald. She wrote a textbook on penmanship when she was teaching and was the author of several articles published in the Missouri Historical Review. She was an honorary member of the Business and Professional women's club.

Speaking of the life of Miss Grover, the Rev. J. C. Hollyman said it was so much a part of the history of the county and Warrensburg in social, cultural, business and educational aspects particularly with reference to the church and the religious life of the community.

"Miss Grover," he said, "had the romance of the pioneer and loved to reminesce, recalling the scenes of the past, particularly those which were most beautiful. She and the members of her family were buiders. She grew up with the first generation of this city when the railroad and the city institutions were being founded. "She was loyal to her conviction," Dr. Hollyman continued, "but exercised tolerance for those who disagreed with her. She spok her mind in a pleasant way and we reverence and respected her. She had the viewpoint of youth, but was not childish, and carried with it an interest mellowed by the experience of age."

Elizabeth wrote many articles about Warrensburg's history. Including one about the history of the Presbyterian church. https://1973whsreunion.blogspot.com/2017/04/1852-first-presbyterian-church-founded.html According to local resident, Lucille Mock, older church members still tell the story about how Lizzie Grover, brought some members up before the church board to be censured for dancing.

She also enjoyed composing poetry.

In 1946, Jack Grover of Kansas City, who was by then a prominent lawyer and football official, sold the last undeveloped part of the Grover farm to the Mathews-Crawford Post of the American Legion. C. S. Baston a Post member, was the board's agent in completing the deal and later loaned the post the money to buy the land at four per cent interest when others were getting a much higher rate. Mr. Grover also gave funds for a memorial plaque He stipulated that the park should be known as Grover Memorial Park.

Jack Grover died in 1950 and was buried in the Grover plot in Sunset hills.

Anna Gardner Harris was chosen to head the department of foreign languages for several years before her retirement in July 1953. She was a member of the Arts Books, and crafts club and the American Association of University Women, She was a sponsor of the Pi Kappa Sigma social sorority on the campus of Central Missouri State College for many years. She was a member of Kappa Delta Pi and Delta Kappa Gamma honorary fraternities, in addition to belonging to other honorary foreign language fraternities. She was a member of the Christ Episcopal Church and the Johnson County Republican Women's Club. She spent much of her time after retirement writing articles and giving speeches about her family's history.

She lived at 118 Ming Street.

In 1953 Anna, a member of the local chapter of the DAR, gave a speech to that group about her grandfather, Benjamin Grover. She passed the silver pitcher presented to him in February, 1856, to the audience for inspection. That is the last record of the pitcher appearing in public. The pitcher remained in her possession for the rest of her life.

John C. Grover, 66, lawyer

During the lifetime of his aunt, Miss Lizzie Grover and uncle, Robert C. Grover, Jack Grover came here on occasions to visit them. He had also officiated at sports events at the college. John was an honor graduate of the Warrensburg High School, the Normal School and was on the honor roll at Washington University. He was a pupil of J.L Ferguson, athletic director of the Warrensburg Normal. He was referee in university football for twenty-five years and acted as official of university track meets.

Although he lived most of his life in Kansas City, Jack Grover's remains were returned to Warrensburg to be buried when he died in 1950.

Grover Park

A Veterans Day dedication was held Tuesday morning at 11 o'cock at the Grover Memorial Park on East Gay Street, Warrensburg, an outstanding recreational area of the city The occasion was the presentation of the deed to the park to the city by the Legion Post.

The plaque is engraved with "Grover Memorial Park - Donated to the City of Warrensburg, Mo., in memory of those men who gave their lives in the two Great Wars by Matthews-Crawford Post No. 131, the American Legion."

The dedicatory service was held at the Eat Gay street entrance of Commander Drive to the Park beside the memorial plaque which is on a concrete base and encircled by a chain at the top of posts, and in front of four hand-cut stone columns dedicated by the Citizens Bankof Warrensburg. The columns were from the original bank building which was erected in 1893 and had been hand cut at the site of the building.

The memorial arrangement was designed by Sam Rowell of Florida, former Warrensburg resident. The work of mounting the plaque and columns and the concrete base was donated by O. S. Stump & Son, Contractors. The inscription or legend was by Ralph Martz, Earl Uhler, and James S. Whitfield, former past commanders of the post.

Ralph J. Martz, past commander of the Legion Post and past chairman of the City Park Board, presided during the program, which opened with music by the Warrensburg High School band. Mr. Martz read two telegrams, one from the children of Mr. Grover, Bettie Grover Eisner, Las Angeles, Calif, and Jack Grover, a courier for the United State State Department; and the second from Mr. And Mrs. James S. Whitfield of Indianapolis, Indiana.

Seated at the right of the stage and given recognition were members of the board of trustees of Legion Post at the time the park area was purchased from Mr. Grover including A.G. Taubert, Dr. H.F. Parker. A.C. Bsss, Dr. A. L. Stevenson, R.Q. Phillips, Claude Grainger and C.S. Baston, Seated with them and also given special recognition was Miss Anne G. Harris, cousin of Jack Grover and only member of the Grover family residing in Warrensburg.

Tribute was slso paid to the late A.W. Rodenberg and W.S. Moore, who were members of the board of trustees at the time the post purchased the land for the park.

Invocation was by R. Q. Phillips, honorary chaplain, followed by the pledge of allegiance led by the post commander, Dr. W. S. Reed, and the "Star Spangled Baner" played by the Warrensburg High School band.

A.T. King, past commander, who was one of the founders of the American Legion in Paris, France at the close of World War I, gave a history of the park following which he presented the deed of the park from the post to the city. Mayor H. H. Russell accepted the deed on behalf of the city stating that the Grover Memorial Park was a memorial to veterans of all wars and the Grover family, of which the city is proud, and that he was sure Jack Grover would be proud of the dream he had. He paid tribute to the Garden Clubs, Park Boards and all firms and others who contributed to the improvement of the park. He said the city appreciated the contribution of the park with all its recreational facilities.

Following a memorial silence the benediction was given by the post chaplain, Henry Goucher. Rounds were fired by the firing squad, composed of Ralph Newland, Seergeant, William J. McGinnis, John Bruch and Dewey Davis. Taps were sounded in the distance, following which the Warensburg High School band played as the audience left.

Martz became president of the park board in 1952 and in August of the same year a work day at the park was held. The results were unbelievable. All areas were cleared. Mitchell street was graded and all brush cleared away. It was estimated that the use of $75,000 worth of equipment was donated and 200 persons contrubuted their labor. In the fall of 1952, contour maps were made by the board and submitted to the state. The park was not completely filled until 1957 when dirt was secured during the college building program.

The Lions Club furnished funds for lighting the park, including the ball diamond, and the Missouri Public Service Company conrubuted much. the rotary Club furnished the picnic ables and the Garden Clubs helped with landscaping. the Lions Club and Odd Fellow lodge financed the shelter house and fireplace. The County Highway Department graded Commanders Drive. the Ready-Mix Concrete Company furnished much concrete. John M. Werling, head of the J& M company at that time, now John M. Werling and Son, Salvors donated playgroung equipment. Much work was donated by G. L. Stump & Son Contracting Comapny and others. Standard Herald, Nov. 14, 1958.

When she died in 1962, Anne Harris left the pitcher to a cousin. As of 2018 no one at the Historical Society knows who the cousin was or where the silver pitcher is now.

No comments:

Post a Comment