Dr. Forrest C. 'Phog' Allen once lived, coached here in Warrensburg at the University of Central Missouri

Jan 3, 2010, 12:41 AM

By NATE TAYLOR, Muleskinner Sports Editor

At age 26, Phog Allen accepted an offer from State Normal School No. 2, what is now UCM, as the head of physical education. He later went on to work for KU, where, between the years 1919-1958, he won three national championships and 24 conference titles.

WARRENSBURG, Mo.--This drive to a small community in Missouri, could mean very little. Or, something special might unfold. Either way, Judy Allen Morris didn’t really mind.

Morris knew her grandfather was an important person. He lived in this small town for seven years – seven years that shaped his life – and, now, people from this town wanted to talk to Morris and her brother, Mick Allen, about what their grandfather meant here.

So, as Morris sat in the passenger’s seat while her brother drove them through this rural countryside to Warrensburg on a dark, chilly morning with heavy rain, she wondered what awaited them.

“What do you think they’ll do?” Morris asked her brother.

“I don’t know,” he said.

What led to her uncertainty was she and her brother didn’t know these people. They hadn’t spent significant time with anybody in town. And because their grandfather, the legendary Forrest “Phog” Allen, had died more than 25 years ago, how could he be so important to Central Missouri now?

Finding the answer was enough for Morris to join her brother on a one-day trip, and once the two arrived on Jan. 24, 2003, they were surprised.

“I thought we were just passing the torch or something,” she said. “Instead, they treated us like celebrities.”

The University had prepared a luncheon, and in some ways, the occasion felt initially like just another event to honor her grandfather, Morris thought. But people kept asking her the same question: What was Phog Allen like?

She hadn’t heard that question in a while. To hear it now startled her – in a good way. Morris soon found the answer in each person’s eyes: The people revered her grandfather and wanted to learn more about him.

That was good enough for Morris. Their curiosity made her eager to open up about the legendary college basketball coach with the strong Central Missouri ties.

A grandfather's concern

Judy Morris has lived most of her life in Lawrence, Kan., the city where her grandfather became one of college basketball’s biggest names.

She remembers a lot about her grandfather. She rattles off the time she sat behind him while he coached the Jayhawks; she mentions hearing him lobby for basketball to become an Olympic sport; and she describes seeing Wilt Chamberlain sitting on the family couch when her grandfather offered Chamberlain a scholarship to be a Jayhawk.

No one needs to remind Morris whose name is on Kansas’ arena. A nine-foot bronze statue of her grandfather stands tall outside Allen Fieldhouse. Inside, a banner hanging above the court reads, “Pay Heed, All Who Enter: BEWARE OF ‘THE PHOG.’”

Sure, the KU community recognized his records and achievements in athletics, but it wasn’t enough for Morris.

“My grandfather should be known for more than just basketball,” she said.

Morris kept wondering: Do they know the person or just the legend?

A coach is born

Basketball always had Phog Allen’s attention. Growing up with five brothers, he was addicted to the game, with friends to support his habit. In his youth, Allen developed his shooting skills to later become a two-time All-American at Kansas.

Allen also played for James A. Naismith, the inventor of basketball. In 1906, Naismith felt basketball was too spontaneous to be coached. Still, his philosophies helped to mold Allen.

As basketball was growing in popularity, Allen believed teaching the game’s nuances might have value, an idea that ran counter to Naismith’s.

“You can’t coach basketball, Forrest,” Naismith told him. “You play it.”

The conversation – and idea – could have ended there. Luckily for the sport, Allen had his own theories.

“You can certainly teach free-throwing,” Allen said. “And you can teach the boys to pass at angles and run in curves.”

Allen was proven right. The following season, he replaced Naismith as coach and led Kansas to the Missouri Valley Conference title. Then, from 1919-1958, Allen became the best coach of his era. He won three national championships and 24 conference titles.

“He was the first guy to know coaching was important,” said Blair Kerkhoff, author of the book "Phog Allen: The Father of Basketball Coaching." “He thought you could win games solely on coaching and strategy.”

By rejecting Naismith’s philosophy, Allen, in the most unlikely way, became the most influential sports figure of his time.

Old stories revealed

This luncheon wasn’t just a bunch of people sitting at tables talking about Phog Allen. No, Judy Morris sensed a family atmosphere. After all, if you knew her grandfather, you’re considered family.

Judy McClure had made the phone call. If anything, she was the reason Morris and Mick Allen were in Warrensburg. McClure’s late husband Arthur, a KU grad, fell in love with Phog Allen’s history. As UCM chair of history and anthropology for 30 years, Arthur McClure wanted to write Phog Allen’s biography, but when her husband died in 2002, Judy McClure knew what do to next: donate all the items her husband had found on Phog Allen to James C. Kirkpatrick Library.

There were a lot of materials for the archives, too: boxes of old photographs, newspaper articles and letters Phog Allen wrote to players during the war years – letters detailing aspects of his life.

Judy McClure knew her husband had visited Morris and Mick Allen, thus to celebrate the donation, she made sure they attended the luncheon.

Throughout the day, Morris learned her grandfather had refereed Central Missouri’s first-ever basketball game in 1905. She also found out he played forward for Central Missouri – even though he was the coach. Morris was beginning to see the historical link between her grandfather and Warrensburg.

“The appreciation that was shown,” Morris said, “you could tell they cared.”

The person who sifted through all the materials was Vivian Richardson, the assistant director of UCM archives. Richardson showed Morris and her brother all the research on their grandfather.

“They were excited over the amount of information we had on Phog,” Richardson said. “They were very happy that we as a college still remember him so well.”

Tales about her grandfather traveled around the Union Ballroom for what seemed like a decade. With each conversation Morris had, she saw people paint a more vivid picture of her grandfather.

For Morris and her brother, it was as if they had gone back in time.

Warrensburg accepts Phog

Phog Allen and Central Missouri needed each other.

Central wanted a lot of things: A person who could take their young athletic program to the next level, build new facilities and win conference titles. Allen had to find a school that allowed him to see if his two passions--coaching and medicine--could coexist.

After leaving KU in 1909, Allen enrolled at the Kansas City College of Osteopathy. There, he learned taking care of the body could be a key part of athletics. Allen immersed himself so much in human health that he turned down coaching jobs at Washburn, Westminster College, West Point, and William Jewell in order to graduate with the only degree in his life in 1912.

Anxious to treat patients, he wanted to put his work into his practice. But with doctors waiting an average of two years to find work back then, Allen couldn’t wait.

Coaching had been his backup plan, and he decided to put it into use.

At the age of 26, Allen accepted an offer from State Normal School No. 2, known now as Central Missouri, to become the head of physical education. His salary was $1,600 per year.

Turning down a $400 raise, Allen left Central Missouri with an 84-31 record as basketball coach. That June, Allen told school officials he would devote his time to his medical practice, seemingly in an effort to get back at the board.

“One thing we know about Phog was he had an ego,” Kerkhoff said. “Early in his life, Phog set out to prove Naismith wrong. He thought he could be a coach, so he became a coach. He thought he could be an AD, so he became an AD. I think that ego was a reason people in the MIAA didn’t like him, either.”

Even if multiple issues ruined Allen’s time at Central Missouri, he never had a negative thing to say about Warrensburg. Even after he had become the iconic figure at Kansas, Allen returned to Warrensburg often – mostly to spend time with Russell, who shared the same birthday as Allen.

“It was the greatest opportunity that ever happened to him,” Russell said of Allen’s resignation, “because then the position of athletic director became available at KU.”

But it was the work Allen did at Central Missouri that landed him the job.

“What Phog learned most from his time in Warrensburg was being an athletic director,” Kerkhoff said. “That is what served him really well and what led him back to Kansas.”

That was the point Central Missouri showed Judy Morris and Mick Allen – without Phog Allen’s seven years in Warrensburg, their grandfather might never have become a college basketball legend.

Driving home as Mules

Serious basketball fans know the rest of the story – that Phog Allen rejoined Kansas one month after leaving Central Missouri and built the Jayhawks into a powerhouse.

Still, that knowledge wasn’t enough for Morris.

Since Jan. 24, 2003, she has tried to make certain her grandfather’s legacy never leaves this small town in Missouri. All the Phog Allen artifacts she left remain in the library for people to see. Morris wants her grandfather’s connection with Central Missouri to stay strong. “It just felt like they knew more about him at the university level there than a lot of people do here in Lawrence,” she said. “It just seems like people in Warrensburg had more knowledge of the man.” To end the luncheon, Morris and Mick Allen were asked to stand at the front of the ballroom. Men’s basketball coach Kim Anderson and athletic director Jerry Hughes presented the siblings with commemorative jerseys – “Allen” stitched on the back. On that day, Morris and her brother became Mules, just as their grandfather had been.

Only Morris didn’t know she would be taking a piece of Warrensburg back with her to Lawrence.

On the 90-mile drive back home, Mick Allen was still the driver. The cold rain was still coming down, too. So, as Morris sat in the passenger’s seat, she looked to her brother and smiled.

He smiled back.

There was no music. No talk radio, either. There were just two grandchildren talking about how much their grandfather meant to the people of Warrensburg.

Forrest (Phog) Allen was a child when basketball was invented by James Naismith. At the age of ten, Allen and his brothers formed a basketball team. At that time the rules developed by Naismith allowed only one player to shoot the free throws. For the Allen basketball team, Forrest was that player.

Allen became a student at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, in 1904. His basketball coach was the famed inventor of the game, James Naismith. In 1905, Forrest also played for the Kansas City Athletic Club. It was his idea to promote the game by conducting a "World’s Championship of Basketball". The Kansas City team was to play the touring Buffalo (N.Y.) Germans in the Convention Hall. Each of the games was to have a different referree, with James Naismith doing the honors for the third game. Allen, once again the designated free thrower, hit 17 of his attempts and the KCAC team won the national championship. While Allen continued to play for KU, he also coached the nearby Baker University basketball team for three seasons from 1905-1908. In 1907, the KU coach, Naismith, decided to leave the university. Although only a senior, Allen was appointed the coach of the team. Under Allen, the Jayhawks won the championship of the newly organized Missouri Valley Conference, in competition with Iowa State College and the Universities of Nebraska and Missouri. They had an 18-4 record that year. Allen expanded his coaching the next year to include not only KU and Baker University but also Haskell Indian Institute. The combined record for the three schools was 74 and 10.

In 1909, Allen left the Jayhawks to study osteopathic medicine. Returning to the university, "Doc" Allen began to coach all sports. He used his knowledge as a osteopathic doctor to treat athletic injuries. He also ran a private osteopathic practice. It was Allen's persuasiveness that led to basketball being accepted as an official Olympic sport in 1936. He coached the United States Basketball team to the championship in the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Finland. Altogether Allen coached college basketball for 50 seasons, compiling a 746-264 record. Upon his retirement he had the all-time record for the most coaching wins among the college basketball coaches. Today Kansas University continues to honor this great coach by playing in Allen Fieldhouse. Allen became a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1959. Allen died in 1974 and is buried in Lawrence's Oakhill Cemetery, near the grave of James Naismith.

Jan 3, 2010, 12:41 AM

By NATE TAYLOR, Muleskinner Sports Editor

| ||

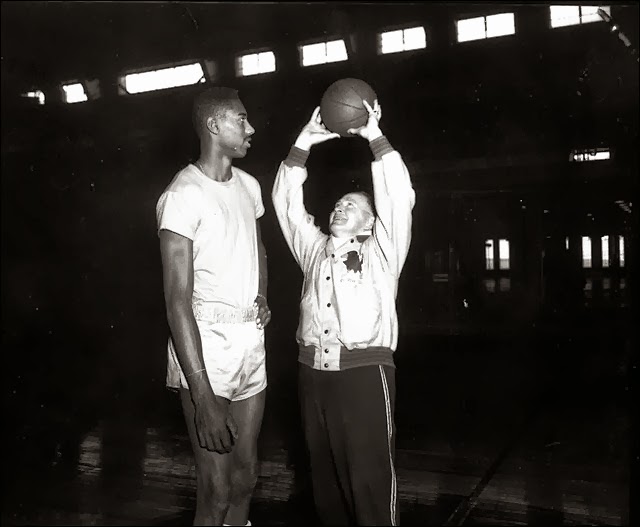

Phog Allen former coach at the Warrensburg State Normal (Universityof Central Missouri) with Dr. James Naismith, inventor of the game of basketball

The 1937 NAIA Men's Division I Basketball Tournament was held in March at Municipal Auditorium in Kansas City, Missouri. The first annual National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) basketball tournament featured eight teams playing in a single-elimination format. In 1938, it would expand to its current size of 32 teams.

This tournament is unique because it was started two years prior to the NCAA tournament and one year before the National Invitation Tournament, and all the teams play over a series of six days instead of several weekends. The compactness of the tournament has given it the nickname "college basketball's toughest tournament".

It began when Dr. James Naismith, Emil S. Liston, Frank Cramer, and local leaders formed the National College Basketball Tournament, which was staged at Municipal Auditorium in Kansas City, Missouri. The goal of the tournament was to establish a forum for small colleges and universities to determine a national basketball champion.[2]

The first championship game featured Central Missouri State University defeating Morningside College (Iowa)35–24. It is also the lowest-scoring championship game in tournament history.

|

|

| Link to Rotary Article |

Morris knew her grandfather was an important person. He lived in this small town for seven years – seven years that shaped his life – and, now, people from this town wanted to talk to Morris and her brother, Mick Allen, about what their grandfather meant here.

So, as Morris sat in the passenger’s seat while her brother drove them through this rural countryside to Warrensburg on a dark, chilly morning with heavy rain, she wondered what awaited them.

“What do you think they’ll do?” Morris asked her brother.

“I don’t know,” he said.

What led to her uncertainty was she and her brother didn’t know these people. They hadn’t spent significant time with anybody in town. And because their grandfather, the legendary Forrest “Phog” Allen, had died more than 25 years ago, how could he be so important to Central Missouri now?

|

| Women's Basket Ball Team Warrensburg Training School c1912 |

“I thought we were just passing the torch or something,” she said. “Instead, they treated us like celebrities.”

The University had prepared a luncheon, and in some ways, the occasion felt initially like just another event to honor her grandfather, Morris thought. But people kept asking her the same question: What was Phog Allen like?

She hadn’t heard that question in a while. To hear it now startled her – in a good way. Morris soon found the answer in each person’s eyes: The people revered her grandfather and wanted to learn more about him.

That was good enough for Morris. Their curiosity made her eager to open up about the legendary college basketball coach with the strong Central Missouri ties.

A grandfather's concern

Judy Morris has lived most of her life in Lawrence, Kan., the city where her grandfather became one of college basketball’s biggest names.

She remembers a lot about her grandfather. She rattles off the time she sat behind him while he coached the Jayhawks; she mentions hearing him lobby for basketball to become an Olympic sport; and she describes seeing Wilt Chamberlain sitting on the family couch when her grandfather offered Chamberlain a scholarship to be a Jayhawk.

No one needs to remind Morris whose name is on Kansas’ arena. A nine-foot bronze statue of her grandfather stands tall outside Allen Fieldhouse. Inside, a banner hanging above the court reads, “Pay Heed, All Who Enter: BEWARE OF ‘THE PHOG.’”

Sure, the KU community recognized his records and achievements in athletics, but it wasn’t enough for Morris.

“My grandfather should be known for more than just basketball,” she said.

Morris kept wondering: Do they know the person or just the legend?

A coach is born

Basketball always had Phog Allen’s attention. Growing up with five brothers, he was addicted to the game, with friends to support his habit. In his youth, Allen developed his shooting skills to later become a two-time All-American at Kansas.

Allen also played for James A. Naismith, the inventor of basketball. In 1906, Naismith felt basketball was too spontaneous to be coached. Still, his philosophies helped to mold Allen.

As basketball was growing in popularity, Allen believed teaching the game’s nuances might have value, an idea that ran counter to Naismith’s.

“You can’t coach basketball, Forrest,” Naismith told him. “You play it.”

The conversation – and idea – could have ended there. Luckily for the sport, Allen had his own theories.

|

| Phog Allen, America's First Basketball "COACH" |

Allen was proven right. The following season, he replaced Naismith as coach and led Kansas to the Missouri Valley Conference title. Then, from 1919-1958, Allen became the best coach of his era. He won three national championships and 24 conference titles.

“He was the first guy to know coaching was important,” said Blair Kerkhoff, author of the book "Phog Allen: The Father of Basketball Coaching." “He thought you could win games solely on coaching and strategy.”

By rejecting Naismith’s philosophy, Allen, in the most unlikely way, became the most influential sports figure of his time.

Old stories revealed

This luncheon wasn’t just a bunch of people sitting at tables talking about Phog Allen. No, Judy Morris sensed a family atmosphere. After all, if you knew her grandfather, you’re considered family.

Judy McClure had made the phone call. If anything, she was the reason Morris and Mick Allen were in Warrensburg. McClure’s late husband Arthur, a KU grad, fell in love with Phog Allen’s history. As UCM chair of history and anthropology for 30 years, Arthur McClure wanted to write Phog Allen’s biography, but when her husband died in 2002, Judy McClure knew what do to next: donate all the items her husband had found on Phog Allen to James C. Kirkpatrick Library.

There were a lot of materials for the archives, too: boxes of old photographs, newspaper articles and letters Phog Allen wrote to players during the war years – letters detailing aspects of his life.

Judy McClure knew her husband had visited Morris and Mick Allen, thus to celebrate the donation, she made sure they attended the luncheon.

Throughout the day, Morris learned her grandfather had refereed Central Missouri’s first-ever basketball game in 1905. She also found out he played forward for Central Missouri – even though he was the coach. Morris was beginning to see the historical link between her grandfather and Warrensburg.

“The appreciation that was shown,” Morris said, “you could tell they cared.”

The person who sifted through all the materials was Vivian Richardson, the assistant director of UCM archives. Richardson showed Morris and her brother all the research on their grandfather.

“They were excited over the amount of information we had on Phog,” Richardson said. “They were very happy that we as a college still remember him so well.”

Tales about her grandfather traveled around the Union Ballroom for what seemed like a decade. With each conversation Morris had, she saw people paint a more vivid picture of her grandfather.

For Morris and her brother, it was as if they had gone back in time.

Warrensburg accepts Phog

Phog Allen and Central Missouri needed each other.

Central wanted a lot of things: A person who could take their young athletic program to the next level, build new facilities and win conference titles. Allen had to find a school that allowed him to see if his two passions--coaching and medicine--could coexist.

After leaving KU in 1909, Allen enrolled at the Kansas City College of Osteopathy. There, he learned taking care of the body could be a key part of athletics. Allen immersed himself so much in human health that he turned down coaching jobs at Washburn, Westminster College, West Point, and William Jewell in order to graduate with the only degree in his life in 1912.

Anxious to treat patients, he wanted to put his work into his practice. But with doctors waiting an average of two years to find work back then, Allen couldn’t wait.

Coaching had been his backup plan, and he decided to put it into use.

At the age of 26, Allen accepted an offer from State Normal School No. 2, known now as Central Missouri, to become the head of physical education. His salary was $1,600 per year.

|

| One of Dr. Phog Allen's Teams at Warrensburg State Normal, MO |

The hiring created a buzz in Warrensburg, and Allen didn’t take long to build a winner.

In his first year as coach of football, basketball and baseball, Central Missouri won all of its conference games. Allen learned in his first year that his medical background gave him an advantage – he could keep his players in better shape and heal them quicker than other coaches.

“Warrensburg,” Morris said, “is when he realized these two things fit well together.”

Allen was also one of the best coaches.

In his book, "Better Basketball," Allen theorized a shot from around the free-throw line – either from the field or the foul line – was responsible for more victories than any other two shots combined. His philosophy was to have his players hear his message in their sleep: “Guard as if your arms were cut off at the elbows. ... The knees are the only springs in the body – bend them! ... Pass at angles. … Run in curves.”

“This was at a time when people were still learning how to play the game,” Richardson said. “He brought a winning spirit to the school.”

Allen won the fans over with a 23-22 win over the Kansas Aggies, known now as Kansas State. Playing against an Aggie team that had beaten KU twice that year, Allen led the “Normals” to what the student newspaper at the time called, “the most thrilling game of basketball ever seen on the Normal court.”

|

| Dr. Phog Allen |

In the 1913 upset, Allen used his medical training to keep one of his players in the game after treating him for an ankle injury. The fact his team was better conditioned than the Aggies proved even more important as the Normals scored four of the game’s final six points.

It marked the school’s first victory over a bigger school.

“We owe a lot to him,” Richardson said. “KU had him for a long time, but he certainly helped build this program.”

|

| Another of Dr. Phog Allen's BasketballTeams at Warrensburg State Normal |

The people of Warrensburg loved Allen. They supported his side business as well. With his medical office in the basement of his three-room house on Broad Street, Allen helped anybody who needed treatment.

“Taking care of people always intrigued him,” Morris said. “Being a coach gave him the chance to connect with people in a way being a doctor just couldn’t.”

|

| Forrest C. "Phog" Allen, D.O. Professor of Physical Education, Warrensburg, MO |

Both parties had succeeded. Allen won with his medicine and became the most public figure in town. And for Warrensburg, they thought Allen would never leave, only to turn Central Missouri into a big-time place for college sports.

|

| Dr. Forrest C. "Phog" Allen, Athletic Committee Chairman, State Normal College Warrensburg, MO |

Controversy leads to Kansas

There are certainly myths when it comes to legends, and with Phog Allen, this one wasn’t answered for 55 years: Just why did he stop coaching in Warrensburg?

There were a lot of candidates – the MIAA expelling the Normals for five years, the Normal School at Kirksville accusing Allen of using football players who were not students or the University of Illinois, who signed Allen to become its assistant football coach in 1917 before World War I cancelled the season. Each theory seemed to have some merit, but none were completely true.

H.H. Russell (our grandfather) knew the answer.

As a football player for Allen, Russell let the truth out after his coach 88 died Sept. 16, 1974, at age 88.

“His last year at Warrensburg was terminated because there were two medical doctors on the Board of Regents,” Russell told The Warrensburg Daily Star-Journal. “They apparently disliked the fact that ‘Doc’ maintained his osteopathic practice in his spare time, after school, on weekends and holidays.

“So … in the spring of 1919, the board delivered an ultimatum to Dr. Allen. He would have to be their full-time coach and give up his practice, or else give them his resignation, which, of course, he did.”

Turning down a $400 raise, Allen left Central Missouri with an 84-31 record as basketball coach. That June, Allen told school officials he would devote his time to his medical practice, seemingly in an effort to get back at the board.

“One thing we know about Phog was he had an ego,” Kerkhoff said. “Early in his life, Phog set out to prove Naismith wrong. He thought he could be a coach, so he became a coach. He thought he could be an AD, so he became an AD. I think that ego was a reason people in the MIAA didn’t like him, either.”

Even if multiple issues ruined Allen’s time at Central Missouri, he never had a negative thing to say about Warrensburg. Even after he had become the iconic figure at Kansas, Allen returned to Warrensburg often – mostly to spend time with Russell, who shared the same birthday as Allen.

“It was the greatest opportunity that ever happened to him,” Russell said of Allen’s resignation, “because then the position of athletic director became available at KU.”

|

| One of Dr. Phog Allen's Football Teams at Warrensburg State Normal Lifelong Friend H H Russell bottom row, 4th from the right. |

“What Phog learned most from his time in Warrensburg was being an athletic director,” Kerkhoff said. “That is what served him really well and what led him back to Kansas.”

That was the point Central Missouri showed Judy Morris and Mick Allen – without Phog Allen’s seven years in Warrensburg, their grandfather might never have become a college basketball legend.

Driving home as Mules

Serious basketball fans know the rest of the story – that Phog Allen rejoined Kansas one month after leaving Central Missouri and built the Jayhawks into a powerhouse.

Still, that knowledge wasn’t enough for Morris.

Since Jan. 24, 2003, she has tried to make certain her grandfather’s legacy never leaves this small town in Missouri. All the Phog Allen artifacts she left remain in the library for people to see. Morris wants her grandfather’s connection with Central Missouri to stay strong. “It just felt like they knew more about him at the university level there than a lot of people do here in Lawrence,” she said. “It just seems like people in Warrensburg had more knowledge of the man.” To end the luncheon, Morris and Mick Allen were asked to stand at the front of the ballroom. Men’s basketball coach Kim Anderson and athletic director Jerry Hughes presented the siblings with commemorative jerseys – “Allen” stitched on the back. On that day, Morris and her brother became Mules, just as their grandfather had been.

Only Morris didn’t know she would be taking a piece of Warrensburg back with her to Lawrence.

On the 90-mile drive back home, Mick Allen was still the driver. The cold rain was still coming down, too. So, as Morris sat in the passenger’s seat, she looked to her brother and smiled.

He smiled back.

There was no music. No talk radio, either. There were just two grandchildren talking about how much their grandfather meant to the people of Warrensburg.

|

| Dockery Gymnasium Under Construction Where Dr. Phog Allen would later Coach |

|

| From The Student Rhetor ca1916 Missouri State Normal School at Warrensburg |

|

| Dr. Phog Allen Coached here, Today it is the Business School for UCM, Warrensburg. |

Forrest "Phog" Allen

Basketball coach. Born: Nov, 18, 1885. Jamesport, MO. Married Bessie E. Milton. Died: September 16, 1974, Lawrence, Kan.

Basketball coach. Born: Nov, 18, 1885. Jamesport, MO. Married Bessie E. Milton. Died: September 16, 1974, Lawrence, Kan.

Forrest (Phog) Allen was a child when basketball was invented by James Naismith. At the age of ten, Allen and his brothers formed a basketball team. At that time the rules developed by Naismith allowed only one player to shoot the free throws. For the Allen basketball team, Forrest was that player.Allen became a student at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, in 1904. His basketball coach was the famed inventor of the game, James Naismith. In 1905, Forrest also played for the Kansas City Athletic Club. It was his idea to promote the game by conducting a "World’s Championship of Basketball". The Kansas City team was to play the touring Buffalo (N.Y.) Germans in the Convention Hall. Each of the games was to have a different referree, with James Naismith doing the honors for the third game. Allen, once again the designated free thrower, hit 17 of his attempts and the KCAC team won the national championship. While Allen continued to play for KU, he also coached the nearby Baker University basketball team for three seasons from 1905-1908. In 1907, the KU coach, Naismith, decided to leave the university. Although only a senior, Allen was appointed the coach of the team. Under Allen, the Jayhawks won the championship of the newly organized Missouri Valley Conference, in competition with Iowa State College and the Universities of Nebraska and Missouri. They had an 18-4 record that year. Allen expanded his coaching the next year to include not only KU and Baker University but also Haskell Indian Institute. The combined record for the three schools was 74 and 10.

In 1909, Allen left the Jayhawks to study osteopathic medicine. Returning to the university, "Doc" Allen began to coach all sports. He used his knowledge as a osteopathic doctor to treat athletic injuries. He also ran a private osteopathic practice. It was Allen's persuasiveness that led to basketball being accepted as an official Olympic sport in 1936. He coached the United States Basketball team to the championship in the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Finland. Altogether Allen coached college basketball for 50 seasons, compiling a 746-264 record. Upon his retirement he had the all-time record for the most coaching wins among the college basketball coaches. Today Kansas University continues to honor this great coach by playing in Allen Fieldhouse. Allen became a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1959. Allen died in 1974 and is buried in Lawrence's Oakhill Cemetery, near the grave of James Naismith.

Link to UCM Magazine

Memories of Coach Phog Allen live on

through gift to Archives and Museum

In what some saw as a David and Goliath

basketball match-up, Central faced the

University of Kansas Jayhawks Dec. 4, 2002

in Lawrence with most of the crowd unaware

of the strong coaching history that links both

teams. An important piece of this history will

soon be preserved through a gift of legendary

KU Coach Forrest C. “Phog” Allen research

materials and original items to Central’s

Archives and Museum. Allen, who has been

called “The Father of Basketball Coaching,”

made history at Central prior to his renowned

career at KU. The gift is made possible by

Judy McClure, Warrensburg, and details

many aspects of Allen’s life. It is a compilation

of items that were collected over several years

by McClure’s late husband,Arthur, who

chaired and taught for approximately 30 years

in Central’s Department of History and

Anthropology. In addition to being an educator,

McClure was an accomplished author who

had co-written at least one sports book,

Remembering Their Glory, a collaboration

with Central Professor Emeritus Jim Young

detailing their childhood memories of sports

and its heroes. He planned to write a biography

about Allen, and collected several boxes of

informational materials to aid in the process.

All of these items have been turned over to

John Sheets and Vivian Richardson in the

Archives and Museum, located on the ground

floor of Central’s James C. Kirkpatrick Library.

“I knew that Mr. Allen had served CMSU as

well as KU, and after considering both places,

I felt like the materials would be in good hands

with Vivian and John, who could sort through

them and preserve them so they could be

used by other researchers,” Mrs. McClure

said. Richardson is now taking the lead role

in archiving the items.“When the donation

has been processed, arranged, and a

computerized finding aide developed, the

material will be available to the campus

community and public for research,”

Richardson said. “We will also use the

material in future exhibits in the Archives

and Museum and at other campus locations.”

Items in the collection include clippings from

newspapers, magazines and journals; sports

publications and programs; photographs;

copies of letters written to and from Allen;

radio scripts featuring Allen’s interviews

with sports figures; Jayhawk newsletters;

files about famous sports players during his

coaching years; information about basketball

history, as well as Allen’s mentor, James

Naismith, the inventor of basketball; and much

more. McClure visited with Allen’s grandchildren,

Judy Allen Morris, and her brother, Gary

“Mick” Allen Jr., in Lawrence, Kan. They

provided him with original items such as

a sign-in book of people who visited his

home; letters and copies of letters from

his former players; and copies of letters

he had written to players during the war

years. Mrs. Morris, who was contacted

along with her brother before the gift was

made, said both of them are pleased that

Central will make these items available.

They want others to learn more about their

grandfather’s legacy, possibly with the

same passion that McClure enjoyed.

“Art McClure was so dear, and I really

felt that he understood the essence of Phog.

I was so excited that someone was going

to write something that was about the man.

He was very important in making basketball

an international as well as national sport,”

Morris said.

Born in Jamesport in 1885, Allen’s career

in athletics began as a student at KU in 1904,

where he lettered three years in basketball

under Naismith’s coaching, and two years

in baseball. Allen launched his coaching

career at his alma mater in 1908, but took

a hiatus after graduating in 1909 to study

osteopathic medicine. When basketball was

still in its infancy, he returned to his beloved

sport in 1912 as coach at the State Normal

School No. 2, now the University of Central

Missouri (Warrensburg). Known as “Doc”

to his players and students,he was reputed

to be a colorful figure on the campus, coaching

all sports and becoming known for his

osteopathic remedies for ailing athletes. His

enthusiasm as a coach was evidenced by his

first gridiron victory, a 127-0 thrashing of

Kemper Military Academy. His football,

basketball and baseball teams won numerous

league championships during his seven

years in Warrensburg, at a time when the

MIAA was just beginning. In 1919, he returned

to KU where he was the head basketball coach,

in addition to serving as director of athletics

and football coach. He served as KU’s

basketball coach until forced into mandatory

retirement in 1956 to become professor

emeritus of physical education. During the

46 years he spent at KU, he won 771 games

and lost only 233.

|

| Dr. Phog Allen Recruited Wilt Chamberlain to KU |