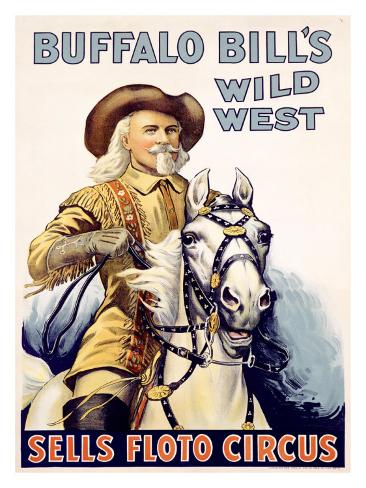

August 21, 1915 "Buffalo Bill" Cody Comes to Warrensburg with - "Sells-Floto" Circus & Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show

Warrensburg Missouri August 21, 1915

Since May 19, 1883, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody had operated his "Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, however, the show went bankrupt in July 1913. After the bankruptcy Tammen hired Cody to perform in his show and renamed the circus the "Sells Floto and Buffalo Bill Circus" for the seasons of 1914 and 1915.

|

| Chief Flying Hawk, Came to Warrensburg in 1915 with Buffalo Bill |

|

| Sells-Floto Band Came to Warrensburg in 1915 (this is picture is not from Warrensburg) |

|

| Sells Floto Circus Sideshow |

|

"Buffalo Bill" Cody was the real deal -- he had hunted buffalo, fought Indians, and scouted along America's vast western frontier. But Cody's biggest achievement came as that frontier vanished -- he brought the "Wild West" to the stage and fairgrounds and wrapped it in a three-hour package.

Union Soldier, Buffalo Hunter

William Frederick Cody was born on February 26, 1846, in an Iowa log cabin. His father Isaac, a farmer with a touch of wanderlust, had been one of the first legal settlers in the Kansas Territory, moving his family there in 1854. A free soiler, Isaac was once stabbed by a pro-slavery man after giving a speech. He died in March 1857, as the territory was wracked by a conflict over slavery known as "bleeding Kansas." Young Will went to work as a messenger and ox herder, and at age 14 he rode for the Pony Express. During the Civil War, Cody served as a "jayhawker" battling Confederate guerrillas from Missouri -- famous outlaw Jesse James fought on the opposing side. His mother Mary Ann had made Cody promise not to enlist, but following her death in 1863, he joined the Union Army, seeing action in Missouri and Tennessee. After the war, Cody married Louisa Frederici and got a job shooting buffalo

Nostalgia for a Vanished Frontier Fighting Natives, Courting Fame

From 1868 to 1872 Cody served as a scout in the wars former Union general Phil Sheridan waged across the Northern Plains against Native Americans. Cody was involved in the summer 1869 campaign that drove the Cheyenne from Kansas, southern Nebraska and northern Colorado, and later that year he appeared as the star of Ned Buntline's novel Buffalo Bill, the King of Border Men, which romanticized his exploits as a jayhawker. In 1872 Cody attended the stage version of the novel in New York City and was asked to make a few remarks, which gave him a bad case of fright. But he was sufficiently recovered to perform in December of that year in a Buntline play called The Scouts of the Prairie. It was said to have been composed in a mere four hours, and Cody was no actor, but audiences loved it -- one critic said the play contained "all the thrilling romance, treachery, love, revenge, and hate of a dozen of the richest dime novels ever written." As for Cody, who had pitch black eyes, flowing hair, and an impressive moustache, one newspaper later remarked, "Everybody is of the opinion that he is altogether the most handsome man they have ever seen." Buffalo Bill performed for the next decade, interrupted only by return summons to serve as a scout. In one incident, during the war against the Sioux of 1876, Cody killed and scalped an Indian named Yellow Hair. He had recently learned of General George Armstrong Custer's defeat at Little Big Horn, and Buffalo Bill apparently exclaimed, "The first scalp for Custer." When word of this spread, it added to his growing fame.

Not content with acting in other people's plays, Cody in 1883 put together what became known as the Wild West, an entertainment that advertisements billed as "A Visit West in Three Hours." By then, the American West had changed irrevocably with the completion of a transcontinental railroad and white settlement of Native lands. As early as 1876, Native Americans had been put on display for millions of visitors at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, and by 1893, young historian Frederick Jackson Turner would famously declare, "The frontier has gone." As the real thing was eradicated, nostalgia for it grew. As early as 1876, Native Americans had been put on display for millions of visitors at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, and by 1893, young historian Frederick Jackson Turner would famously declare,

"The frontier has gone." As the real thing was eradicated, nostalgia for it grew. Actual cowboys and Indians roamed the parade grounds of Cody's show, which featured sharpshooting and reenactments of Pony Express rides, Indian attacks on an authentic "Deadwood stagecoach," and even a recreation of Custer's Last Stand featuring Native Americans who had participated in it. Cody's show would run for 30 years and be seen by presidents and monarchs, as well as millions of Americans and Europeans for whom it would become the depiction of what the West was really like.

Top-Notch Talent

A brilliant showman and first-class rider, Cody performed in the show and also drew in such luminaries as Annie Oakley, whom he initially rejected but then hired in 1885 and kept in the show for almost all of the next 17 years, and Sioux warrior Sitting Bull, who had fought Custer in 1876.

Although he had participated in 14 fights against Indians, Cody harbored no ill feelings towards his Native American performers, and he made sure they were treated the same as the rest of the company. Buffalo Bill even tried to help Sitting Bull during the 1890 ghost dance conflict that led to the Sioux warrior's death, returning to the Dakotas for the first time since 1876.

Sad End

Unfortunately, Cody did not have a good head for business, and after the death of his manager, he fell into debt. After the 1913 season, memorabilia from the Wild West was sold off by creditors, and Cody died bankrupt in 1917.

Buffalo Bill Cody, who later became famous for his Wild West Show, was a rider for the Pony Express and wrote of his experiences. We join Bill's story as he is hired - at the age of 15 - to ride a section of the trail that lies in modern-day Wyoming:

One day when I galloped into Three Crossings, my home station, I found that the rider who was expected to take the trip out on my arrival had got into a drunken row the night before and had been killed; and that there was no one to fill his place. I did not hesitate for a moment to undertake an extra ride of eighty-five miles to Rocky Ridge, and I arrived at the latter place on time. I then turned back and rode to Red Buttes, my starting place, accomplishing on the round trip a distance of 322 miles.. .The next day he [Mr. Slade, the manger of Cody's Pony Express station] assigned me to duty on the road from Red Buttes on the North Platte, to the Three Crossings of the Sweetwater - a distance of seventy-six miles - and I began riding at once.

Slade heard of this feat of mine, and one day as he was passing on a coach he sang out to me, 'My boy, you're a brick and no mistake. That was a good run you made when you rode your own and Miller's routes, and I'll see that you get extra pay for it.'

Slade, although rough at times and always a dangerous character - having killed many a man - was always kind to me. During the two years that I worked for him as pony-express-rider and stage-driver, he never spoke an angry word to me.

Richard Egan Pony Express rider ca. 1861

As I was leaving Horse Creek one day, a party of fifteen Indians 'jumped me' in a sand ravine about a mile west of the station. They fired at me repeatedly but missed their mark. I was mounted on a roan California horse - the fleetest steed I had. Putting spurs and whip to him, and lying flat on his back, I kept straight on for Sweetwater Bridge - eleven miles distant - instead of trying to turn back to Horse Creek. The Indians came on in hot pursuit, but my horse soon got away from them and ran into the station two miles ahead of them. The stock-tender had been killed there that morning, and all the stock had been driven off by the Indians, and as I was, therefore, unable to change horses, I continued on to Ploutz's Station - twelve miles further - thus making twenty-four miles straight run with one horse. I told the people at Ploutz's what had happened at Sweetwater Bridge, and with a fresh horse went on and finished the trip without any further adventure.

Another rider for the Pony Express was Wild Bill Hickok, a friend, and mentor of Buffalo Bill. Buffalo describes an incident when his friend was riding the trail:

"The affair occurred while Wild Bill was riding the pony express in western Kansas.

The custom with the express riders, when within half a mile of a station, was either to begin shouting or blowing a horn in order to notify the stock tender of his approach, and to have a fresh horse already saddled for him on his arrival, so that he could go right on without a moment's delay.

One day, as Wild Bill neared Rock Creek station, where he was to change horses, he began shouting as usual at the proper distance; but the stock-tender, who had been married only a short time and had his wife living with him at the station, did not make his accustomed appearance. Wild Bill galloped up and instead of finding the stock-tender ready for him with a fresh horse, he discovered him lying across the stable door with the blood oozing from a bullet-hole in his head. The man was dead, and it was evident that he had been killed only a few moments before.

In a second Wild Bill jumped from his horse, and looking in the direction of the house he saw a man coming towards him. The approaching man fired on him at once, but missed his aim. Quick as lightning Wild Bill pulled his revolver and returned the fire. The stranger fell dead, shot through the brain.

Buffalo Bill Cody

'Bill, Bill! Help! Help! save me!' Such was the cry that Bill now heard. It was the shrill and pitiful voice of the dead stock tender's wife, and it came from a window of the house. She had heard the exchange of shots and knew that Wild Bill had arrived.

He dashed over the dead body of the villain whom he had killed, and just as he sprang into the door of the house, he saw two powerful men assaulting the woman.

One of the desperadoes was in the act of striking her with the butt end of a revolver, and while his arm was still raised, Bill sent a ball crashing through his skull, killing him instantly. Two other men now came rushing from an adjoining room, and Bill, seeing that the odds were three to one against him, jumped into a corner, and then firing, he killed another of the villains.

Before he could shoot again the remaining two men closed in upon him, one of whom had drawn a large bowie knife. Bill wrenched the knife from his grasp and drove it through the heart of the outlaw.

The fifth and last man now grabbed Bill by the throat and held him at arm's length, but it was only for a moment, as Bill raised his own powerful right arm and struck his antagonist's left arm such a terrible blow that he broke it. The disabled desperado, seeing that he was no longer a match for Bill, jumped through the door, and mounting a horse he succeeded in making his escape - being the sole survivor of the Jake McCandless gang.

Wild Bill remained at the station with the terrified woman until the stage came along, and he then consigned her to the care of the driver. Mounting his horse he at once galloped off, and soon disappeared in the distance, making up for lost time.

|

RuGw~~60_57.jpg)

Bogg~~60_57.jpg)

yb8BQwObsr-5!~~60_57.jpg)

OhPCLZw~~60_57.JPG)

wFIZQEZ)PPBSNkWnHhmw~~60_57.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment